A Short Vacation

On a winding stretch of the A5 road from North Wales to London – around Betys-y-coed and Llangollen – mountain scenery combined with the challenge of balancing speed, driver satisfaction, and passenger nausea makes the journey almost enjoyable. On the other hand, the interminably boring alternations of dual-carriageway and roundabouts that follow – between Oswestry and Shrewsbury – are a recipe for brain death.

Except, that is, one day last week, returning prematurely from a weather-killed ‘Welsh Break’, my mind buzzed over two critical questions the whole trip: What would our broken tent cost to fix? And why did the grooves on that boulder point to the North East?

Well spotted that woman at the back; this is a post where I obsess about a rock.

The boulder in question sits about a half mile down the old Rhyd Ddu road outside Llanberis in Snowdonia. Its top surface is covered with North East-facing parallel grooves.

And that’s puzzling, because it looks like a moraine boulder dropped by a glacier, in an area where – having walked these valleys for years – I always assumed the ice had flowed towards the North West, away from Snowdon. Seeing as though the scrape marks left by glaciers – which is almost certainly what these are – align with the direction of glacial flow, something is amiss.

At this point, lest I raise galactic doubt and uncertainty beyond already dangerous levels, as Douglas Adams might say, rest assured this is all sorted – after a fashion but in a reasonably scientific way – by the end of the post. I also got a new tent pole: £15 – thanks for asking.

South Sea Wales

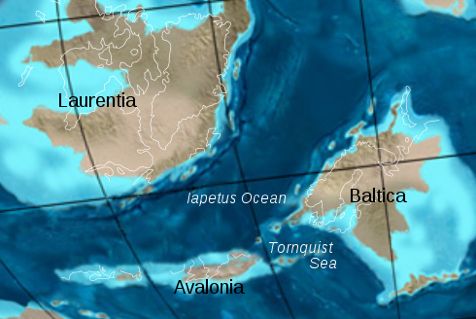

The relevant history starts around 400 million years ago with successive phases of volcanism, weathering, and glaciation (plus some folding and other geological processes). When the oceanic plate of Iapetus undercut the adjacent tectonic plate of Avalonian – all in the Southern Hemisphere back then – the resulting subduction generated enough heat for volcanoes to punch through Avalonia and form the upland region we now call Snowdonia1.

The ensuing millenia saw wind, rain, and rivers transform the resulting mountain range from Himalayan grandeur to the more modest heights we see today; yet some of the most dramatic re-modelling was reserved for only the last 20,000 years or so. And it was caused by ice.

20,000 years ago we were at the peak of a major ice-age that buried the whole region under 1.4 km of ice, with just the tops of the highest mountains poking out. Moving under gravity, glaciers of rock-bearing ice flowed down the river valleys, gouging out the Llanberis, Nant Ffrancon, and other steep-walled passes, cutting through hard volcanic rock in a series of breaches, and scooping out rounded recesses, or cwms (known as corries in Scotland).

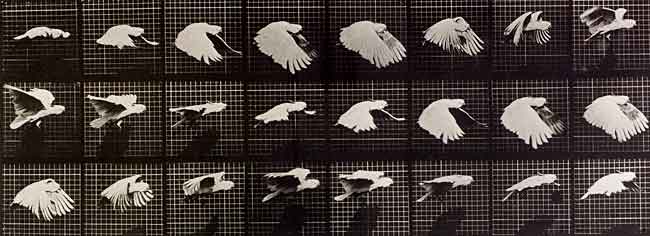

Chunks of rock, liberated by repeated melting and expansion of ice, or plucked out by other rocks, joined the glacier and travelled as an abrasive slurry beneath the ice – scoring anything in their path, before being released as ‘moraine’ when the glacier descended to a warmer altitude or the general climate warmed up sufficiently for the ice to melt.

Boulders falling on the surface of the glacier were likewise dumped, sometimes in incongruous isolation, their angular forms undamaged – like this one just off the Snowdon Ranger Path:

A Popular Destination

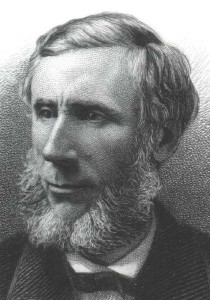

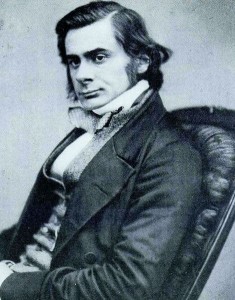

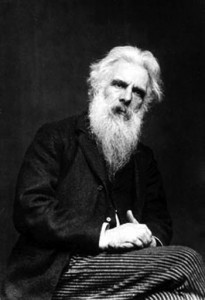

No shortage of historical figures are associated with glaciation and its geographical consequences, including: Louis Agassiz, Charles Lyell, Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel-Wallace, John Tyndall and Thomas Henry Huxley. Agassiz observed glaciers in Switzerland, and in 1840 was the first to suggest similar processes had operated in the upland areas of Britain (an assertion on which he was closely supported by William Buckland and Charles Lyell.)

Charles Darwin knew the region well2:

“I cannot imagine a more instructive and interesting lesson for any one who wishes (as I did) to learn the effects produced by the passage of glaciers, than to ascend a mountain like one of those south of the upper lake of Llanberis, constituted of the same kind of rock and similarly stratified, from top to bottom. The lower portions consist entirely of convex domes or bosses of naked rock generally smoothed, but with their steep faces often deeply scored in nearly horizontal lines, and with their summits occasionally crowned by perched boulders of foreign rock.”

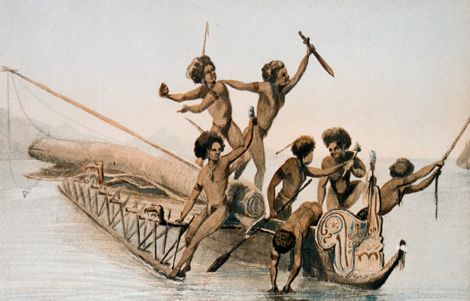

The glacial boulders of North Wales, with their strange grooving, made a particular impression on Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-discover with Charles Darwin of evolution; commenting in his paper Ice Marks in North Wales3:

“..it frequently happens that grooves or scratches are made upon the rocks by the hard materials imbedded in the bottom or sides of the glacier. Owing to the enormous weight and slow motion of glaciers, they move with great steadiness, and thus the markings on rock-surfaces are almost straight lines parallel to each other, and show the direction in which the glacier moved.”

and:

“Nothing is more striking than to trace for the first time over miles of country these mysterious lines, ruled upon the hardest rocks, and always pointing in the same direction.”

Suddenly I feel less alone in my fascination.

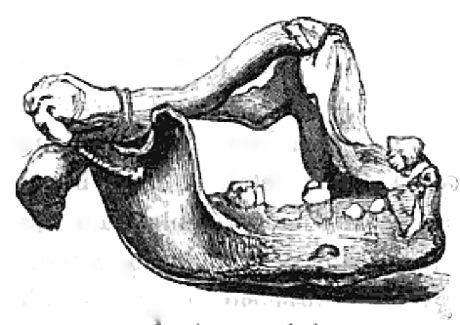

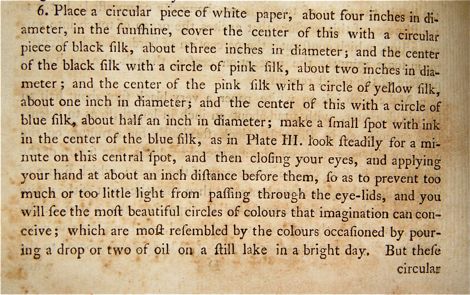

In his hugely popular textbook on physical geography – Physiography4 – Thomas Huxley describes how glaciers flow over exposed bedrock to produce characteristic Roches Moutonnees formations (sheep-backs), complete with parallel striations:

The Mystery Solved?

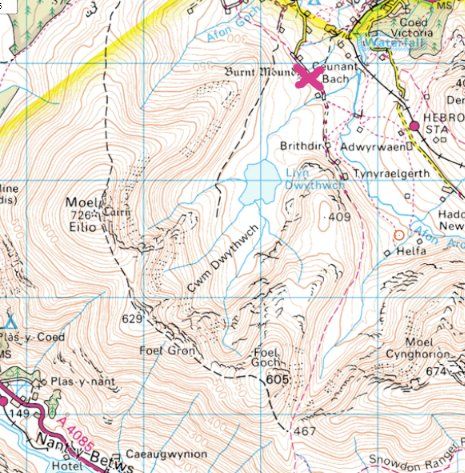

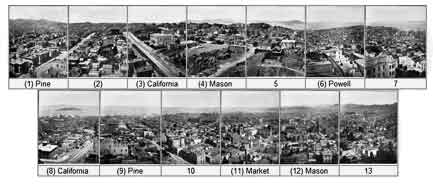

But back now to the North West / North East question; a closer look at the Ordnance Survey and Google 3D map projections suggests an answer.

For directly to the South West of our boulder is a more local gouging of the hills in the form of Cwm Dwythwch and its attendant lake – Llyn Dwythwch, suggesting the area was subject to local glaciation running perpendicular to the main ice-flow from Snowdon. Indeed, the feature is discussed in a paper from the 1950s describing the glaciation as a distinct event, separated from the main ice-flows by 10,000 years in the last period of UK glaciation – the ‘Loch Lomond Advance’. The cwm certainly aligns with our boulder (pink X marks the spot):

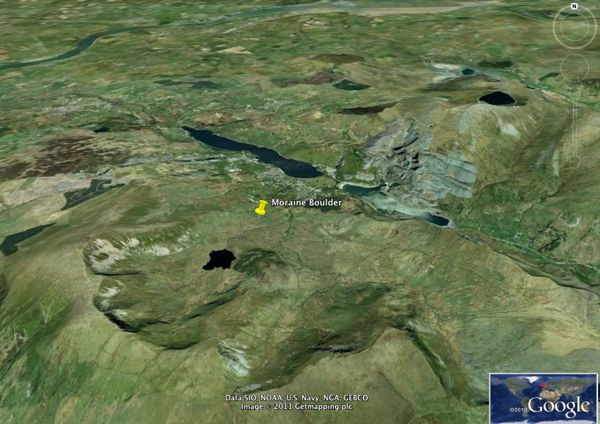

Things are even clearer in glorious Google 3D, North at top:

or looking toward Snowdon:

In Late Glacial Cwm Glaciers in Wales5, Brian Seddon references Cwm Dwythwch and 32 other cwms or cirques in the region arguing they developed from snow and ice preferentially deposited on the sun-sheltered North and North Eastern faces of hillsides, assisted by snow-drifting induced by South Westerly prevailing winds (like we have today). Seddon recorded the moraine fields of 33 such cirques, plotting their altitude(circles) and aspect(radii) to illustrate the dominance of North/North East facing cwms. He placed the lowest extent of moraines in the Snowdon Group, containing Cwm Dwythwch, at 275 metres, which is above, but not far off, our boulder’s height at 240 metres. Maybe he didn’t count every individual boulder at the boundary? That Snowdonia was formed by a mix of ice-cap and localised glaciation is now widely accepted6,7.

All of which, in conclusion, suggests our boulder most likely started life as a volcanic outcrop at the top of Cwm Dwthwch, was carried to its present position by a glacier in a secondary period of low temperatures and glaciation around 10,000 years ago, and picked up abrasions as it was overrun or carried in the North Easterly underflow.

All that with three qualifiers: (a) it’s not 100% certain the boulder is not actually an outcrop of bedrock (need to take a closer look next visit!); in which case it’s fair to assume it was simply overrun by the glacier; and (b) it’s possible the boulder was carried down from Snowdon in the first glacial episode and subsequently overrun by the secondary glacier (again, more research); or even (c) the boulder was scarred in the first episode and somehow got spun around 90 degrees just to fool us.

Clearly no rest for the rigorous – or obsessive weekend geographers – it would seem.

p.s. If any seasoned geologists out there want to put me right / out of my misery, please feel free :-).

References / Sources

1. Rock Trails, Snowdonia: A Hillwalker’s Guide to the Geology and Scenery. Gannon, Paul. Pesda Press, 2008

2. Notes on the Effects produced by the Ancient Glaciers of Caernarvonshire, and on the Boulders transported by Floating Ice, Charles Darwin, The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, 1842, p.362.

3. Ice Marks in North Wales (With a Sketch of Glacial Theories and Controversies) Alfred Russel Wallace, Quarterly Journal of Science, January 1867

4. Physiography: An Introduction to the Study of Nature. T.H.Huxley, Macmillan, 1878, p.162.

5. Late Glacial Cwm Glaciers in Wales. Brian Seddon, Journal of Glaciology, 1957. In International Glaciological Journal, Volume 3, Issue 22 pp.94-96

6. The last glaciers (Loch Lomond Advance) in Snowdonia, North Wales. Gray JM 1982. Geological. Journal 17: 111-133.

7. Allometric development of glacial cirque form: Geological, relief and regional effects on the cirques of Wales, Ian S. Evans, Geomorphology Issues 3-4, 1986

8. The Early History of Glacial Theory in British Geology. Bert Hansen, Journal of Glaciology, Vol 9, No.55, 1970.