Owning multiple copies of a book isn’t that unusual. There’s that extra copy for the bath, the duplicate Christmas present you don’t have the heart to return, or maybe you’ve just made home with someone with similar interests – and library: always a good idea. But no one has hundreds of copies of the same title – do they?

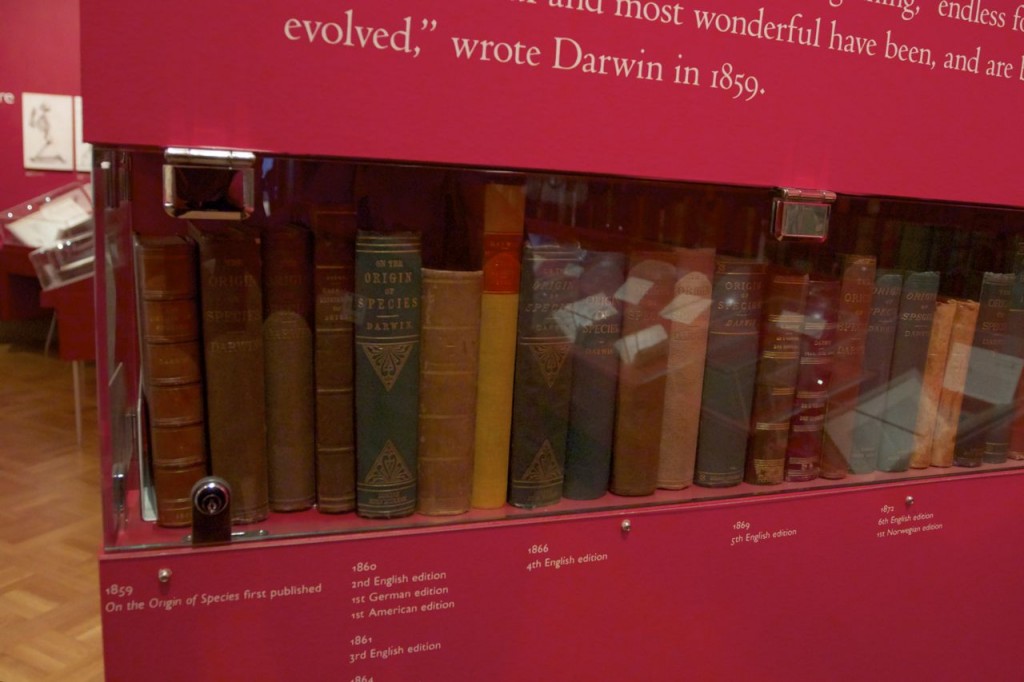

Sure they do. Meet the front end of the Huntington Library‘s 252 strong collection of Darwin’s Origin of Species – all 20 feet of them. I snapped this at the permanent ‘Beautiful Science’ exhibition last month, and have just gotten around to a bit of research:

And turning the corner, here are the rest of them:

And turning the corner, here are the rest of them:

Henry Edwards Huntington acquired much of his collection, now at San Marino, by buying up ready-made collections or even whole libraries. But some books he bought individually, including, in 1860s New York, an 1859 first edition of the Origin of Species in original cloth – for $22.79 (1). Checking Abebooks.com just now, I see you can pick up the same thing in the same city today for a cool $210,000 (Arader Gallery). Nice investment, Henry.

Henry Edwards Huntington acquired much of his collection, now at San Marino, by buying up ready-made collections or even whole libraries. But some books he bought individually, including, in 1860s New York, an 1859 first edition of the Origin of Species in original cloth – for $22.79 (1). Checking Abebooks.com just now, I see you can pick up the same thing in the same city today for a cool $210,000 (Arader Gallery). Nice investment, Henry.

All the Origins at Huntington are different. Most of the variations are reprints of the early six editions published by John Murray between 1859 and 1872; and then there are all the various languages. The original six do vary in content though, with Darwin making material changes in response to readers’ comments.

Despite the title’s legendary status, the print runs of Murray’s Origin look modest by modern standards:

1st Edition (1859) 1,250

2nd Edition (1860) 3,000

3rd Edition (1861) 2,000

4th Edition (1866) 1,500

5th Edition (1869) 2,000

6th Edition (1872) 3,000

which goes some way to explain their value today – although the first editions command disproportionately very much more than any of the others. (For a comprehensive bibliography of all Darwin’s works see Freeman, R. B. 1977. The works of Charles Darwin: an annotated bibliographical handlist. 2d ed. Dawson: Folkstone. and accompanying database at Darwin Online.)

Scholars have argued over the Origin’s scientific content since, well, its origin – so it’s refreshing to find an analysis along a different tack, like Michele and Chris Kohler’s essay about the Origin of Species as a physical object (2).

The authors mention Huntington’s collection of Origins as one of the three largest, along with the Kohler Collection at the Natural History Museum London and the Thomas Fisher Library of the University of Toronto.

Their research also suggests that many more people may have read the first edition than the 1,250 figure suggests, with 500 copies going not to wealthy individuals (books like this were still a luxury for most people) but to Mudies Lending Library – the largest commercial library in the country. (btw, current Origin sales are a respectable 75,000 to 100,000 units per annum.)

There’s also a discussion on how the content was on occasion not so much lost, but subtley changed, in translation, as in the case of Heinrich Bronn’s first German edition.

The Kohlers’ analysis of price history shows a run-away escalation of first edition values in the 20th and 21st centuries: so from an average £36 in the mid-50’s, to still only £4000 in the 80’s, to a top price of £49,000 in 1999; that’s still a long way off the £100,000+ values being achieved today.

The collector demographic has necessarly changed in step: from pure scholars to business people; but perhaps those working in sci-tech related areas who want, and can afford, to be close to a piece of scientific history. Maybe that ownership requires a Henry Huntington income is a good thing – reflecting an increased awareness of the value of it’s intellectual message?

There again, maybe it’s all going the way of the art market, with rare books becoming a commodity currency. What do you think?

References

1. Henry Edwards Huntington, A Biography. James Ernest Thorpe, University of California Press, 1994

2. Essay by Michele and Chris Kohler in: The Cambridge Companion to the Origin of Species, Ed. Michael Ruse, Robert J Richards, New York, 2008 (Archive.org .txt version here)