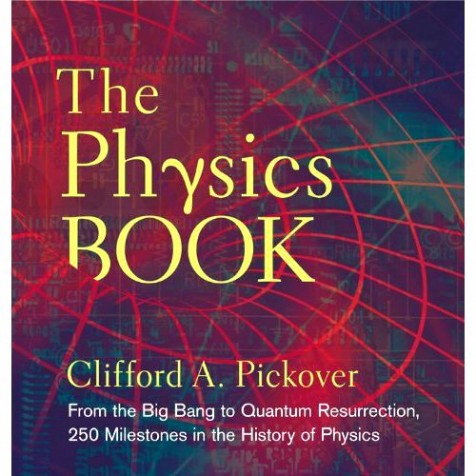

- Hardcover: 528 pages

- Publisher: Sterling (23 Sep 2011)

- Language English

- ISBN-10: 1402778619

- ISBN-13: 978-1402778612

- Product Dimensions: 22.1 x 19.6 x 3.7 cm

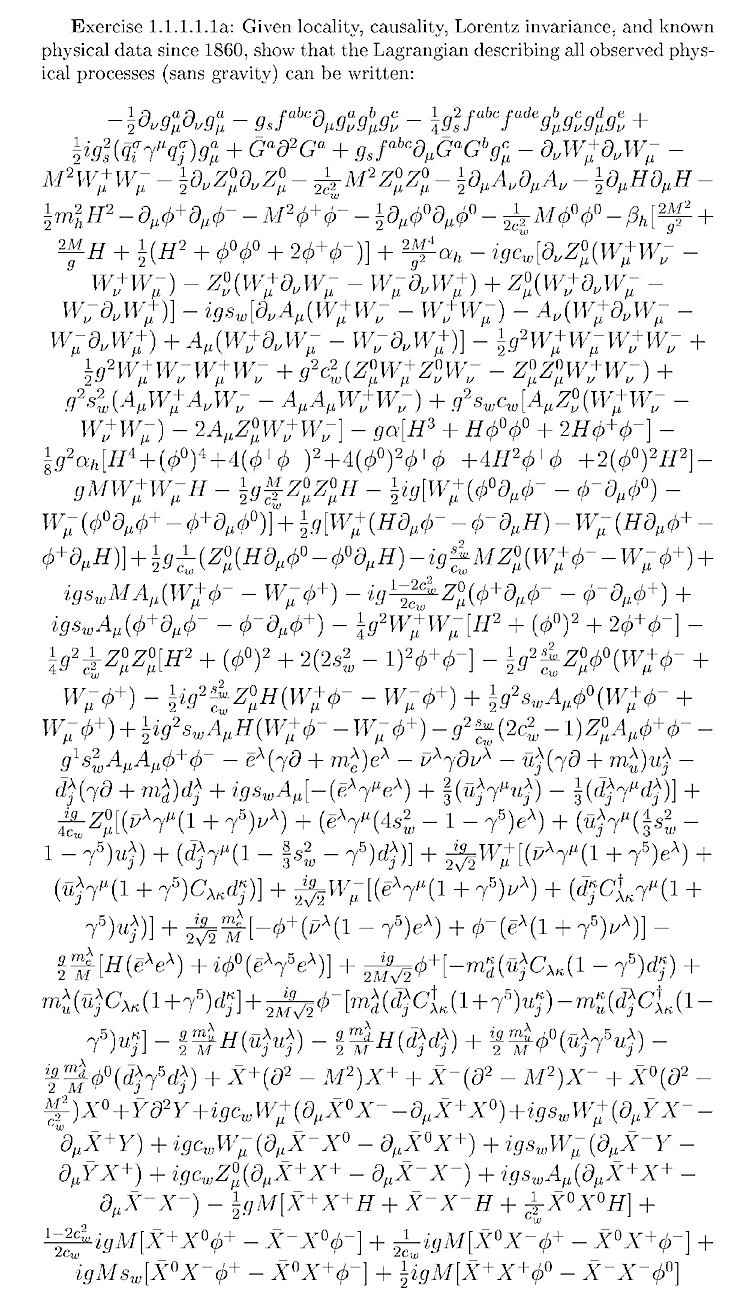

The Kindle’s supremely convenient, and the iPad’s drop-dead gorgeous. So why do I find Clifford Pickover’s good ol’ fashioned hardback version of The Physics Book so damn attractive. And I do mean physically – so to speak. (It’s on iPad too, but read on.)

so damn attractive. And I do mean physically – so to speak. (It’s on iPad too, but read on.)

Maybe I’m getting all bookish-protective in the month that Encyclopedia Britannica wound up its iconic print edition after 244 years? Or is the tactile slabbiness of The Physics Book a nostalgic reminder of the Purnell’s and Marshall Cavendish encyclopedias of my formative years? Well, it’s the latter of course; I almost feel like jumping into short trousers for a re-read.

But enough of my fetishes already.

The Physics Book isn’t really an encyclopedia, but the word kind of fits given the breadth of topics covered. For each of 250 Milestones in the History of Physics, we’re given enough information to be useful in its own right, but with signposting for further research; it’s a kind of physics taster if you like. And while I’m sure it’s readable in two or three good sessions, I found myself dipping in and returning over a period of weeks. So much for prompt reviews then, but this is an eminently dipinable book.

When I reviewed Tweeting the Universe, I was impressed how the authors tackled the unassuming little task of explaining the whole universe in a series of 140 word ‘tweets’. Pickover’s offering is a different animal with much more meat on it, but he’s still had to work, effectively I think, at getting a coherent story for each item into one page of text and an accompanying photograph. Also, Tweeting the Universe doesn’t weigh 1.5kg!

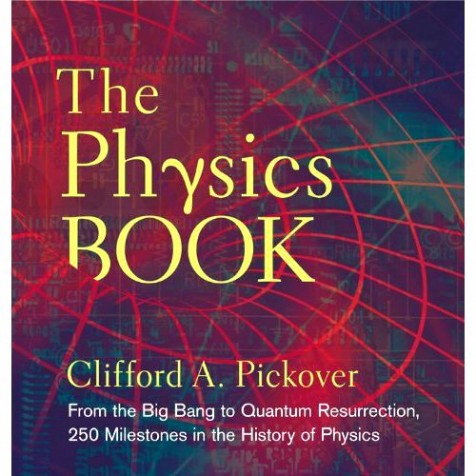

Appropriately kicking off with the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago, the chronological journey is otherwise unsegmented. How could it be? Discoveries don’t just pop up in categories to order. But that also means practical, down-to-earth, physics applications – like the engineering truss – can mingle with less tangible concepts like Pauli’s exclusion principle. And while there’s no talking down to the reader – there are even a few equations! – I think the spattering of examples linking underlying physics to everyday objects and experiences keeps us all onboard.

The engineering references in particular show how some devices we think of as modern were discovered and applied ages ago, even if they weren’t at the time properly understood in a scientific sense; it turns out the first electric battery pre-dated Volta by a whole millenium. In other news, we’ve only recently come to grips with why ice is so slippery – and it might not be why you think. We only figured out how the hourglass works in a 1996 physical modelling study at the University of Leicester (as it happens the city I originally hail from and an area of research technique I used to work in). Other apparently simple observations still lack a satisfactory explanation, like the mysterious black drop effect that happens when Venus transits the sun.

A repeating theme is discoveries being made independently by more than one person, like the explanation of rainbows, calculus, and the laws of refraction: a reminder perhaps that we discover scientific knowledge, not make it up depending on who we are, where we are, or which culture we belong to. There are also lessons in the less than intuitive nature of some relationships, like that between fluid volume and pipe size (Poiseuille’s Law).

The popular association of physics with weapons – typically represented by the iconic atom bomb mushroom cloud – is not neglected or shied away from. Indeed, Pickover describes a range of weapons enabled by physics through the centuries. I knew about the boomerang and crossbow, but the prehistoric atlatl technology, exploiting the principle of leverage to kill mammoths and conquistadors with indiscriminating effectiveness, was news to me.

Pickover’s references are diverse, with lots of modern day and ancient quotations from commentators ranging from Aristotle to Einstein, references to fiction and science fiction, and some pan-cultural associations you wouldn’t expect. Who knew Edgar Allen Poe first suggested a solution to Olber’s Paradox “Why is the sky dark at night?”.

Certain pre-eminent individuals like Newton, Einstein, and Hawking, as sources of particular inspiration, get their own pages. William Gilbert De Magnete gets a mention as the first guy to break god’s monopoly on knowledge and start doing proper experiments, as does Eratosthenes for the shear elegance of his Earth circumference calculation from observation and deduction. Talking of experiments, it’s not the main idea, but there are a few prompts to try stuff at home, like breaking candy bars or pulling off lengths of scotch tape in the dark to see the triboluminescence.

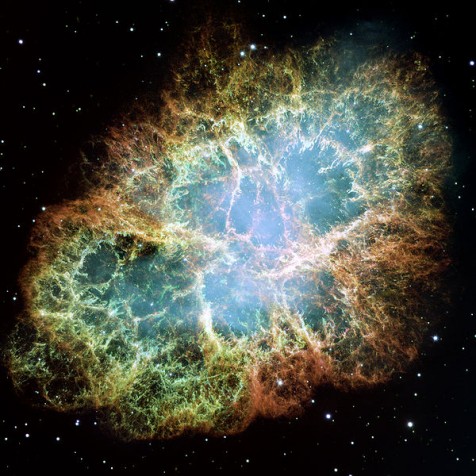

If big picture, left-field, even spooky physics are your thing, ideas like Quantum Mechanics (including Quantum Electro-dynamics) and Heisenberg’s Uncertainty principle are generously discussed; also my favourites: Spooky Action at a Distance (Quantum Entanglement, Bell’s Theorem), and stellar nucleosynthesis. It’s a reminder we’re all made of star stuff, and that reality is weird enough without us making up any extra fairy stories. Other entries in this vein border on the philosophical (another discipline gobbled up by physics?), like the totally plausible if challenging thought that we might all be living in a Matrix-style simulation. Then there is Quantum Immortality – the idea that across infinite multiple universes we might live effectively, necessarily, forever. Likelihood is after that lot you’ll only be good for browsing the photos.

So just as well there are lots of them – precisely 50 percent by page area. My favourite – I think I go for shots with people in them – shows observatory staff posing somewhat precariously on the mount of the University of Pittsburgh’s Thaw refracting telescope. I also like the shot of Stanley and Lawrence standing by their cyclotron. Other pictures illustrate applications – good and bad: like the squat ‘Little Boy’ atomic bomb sitting innocently in its cradle: a simple photograph that evokes so many complex thoughts. Or more constructively, a Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) picture of arteries in the head, for me the ultimate expression of applied, useful, physics. Some pictures are just fun – like Schrodinger’s Cat peeping out of a cardboard box with a “what?” expression on its face.

Moreover, we’re left in no doubt that physics gets everywhere. It’s a bit of a joke across the scientific disciplines, in a sour-grapes sort of way, that all the other sciences are a subset of physics. That’s not the case, but Pickover’s examples for sure underscore physics’ broad reach. I love the way diffusion and Brownian Motion explains the spread of muskrat populations.

So there you go. My impressions and a bit of a content summary of items that stuck with me from The Physics Book. There’s nothing not to like, and despite my reminiscences from childhood, I’m sure readers of all ages and backgrounds will enjoy it – in iPad or ‘real book’ form!

“The truth is stranger than fiction” (Mark Twain and Todd Rundgren)

Other info.

Cliff Pickover’s page on The Physics Book (includes photos)

Preview of electronic version on US iTunes site

Disclosure: I’m grateful to Clifford Pickover for sending me a complimentary copy of The Physics Book