This post is something of a reminisce for me – because – I was there; albeit as an attendee, not a competitor, at Leicester’s Gateway Grammar School. Although too young to participate, I saw the effect the show had on the school, its pupils, and the viewing public.

So, beyond the nostalgia, can we learn something from the Young Scientists phenomenon?

The show’s origins trace back to the formation in 1963 of the Science and Features Department of the BBC: the group that gave us Tomorrow’s World, the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures, and the iconic productions of Jonathan Miller, Jacob Bronowski and David Attenborough. The team also produced Heinz Wolff’s next project after Young Scientists – The Great Egg Race.

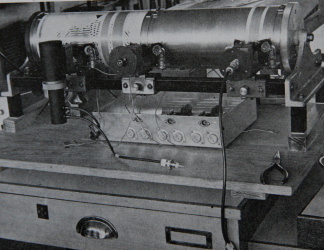

Production entailed a combination of material filmed at the participants’ schools, cut with Q&A sequences from the studio. During the judging, contestants sat nervously with their rigs as backdrop.

My school participated twice. A project on PVC reached but floundered in the final, while an invention that automatically scanned fingerprints won in the UK final and the competition’s European equivalent, hosted by Phillips in Eindhoven. The self-effacing commentary of the PVC team, reproduced from the School Magazine, reveals the production pressures, and gives an honest insight into how laboratory science really works when delivering breakthroughs to order.

” We had won the heat largely on the technical achievement of building the machine and so we made it our policy to concentrate on doing some research with it rather than make modifications to improve its working. With reactions taking up to eight hours and only a few weeks to go before the recording of the final, we had to start working late again and on occasions were still at school at about 2 a.m. During this time we managed to produce two polymers, B.S.R. and P.E.O. but with the limit on our time we were able to complete only a preliminary investigation into these polymers. From these results we managed to draw a few vague conclusions and plan our future research. Armed with this we went to Birmingham for the recording of the final. We were not so apprehensive about what would happen this time as we had the experience of our first visit behind us. As expected, the procedure was much the same as before and we approached the day for judging and filming in a much calmer state of mind than on the first occasion. However, as soon as the first judge, Sir George Porter, began to question us we began to realise that all was not going well. He continually probed us about details of the process which we had only just begun to study. Because of the short period of time which was available to us between heat and final we had not been able to familiarise ourselves with all aspects of the chemistry of the process. Consequently our answers to our questions were rather vague and lacking in the detail that he seemed to want.“

The series ran for nine years on BBC1. Why so successful? The popularity, I suggest, was partly due to the show’s tangible competitiveness – the ‘tune in again next week’ factor. The content itself was made accessible through the pupils’ explanations and chatty atmosphere of the studio. By raising the status of school science and ordinary pupils, there may even have been some flattery of parents by association.

Were there deeper benefits beyond entertainment value? Who knows how many fifteen year olds were swayed to science A-Levels by an inspiring episode of Young Scientists? I believe the participant schools were strengthened by the experience, and others motivated to reach the grade. Involvement would encourage higher quality teacher and pupil applicants to the school, and raise the school’s status with universities and employers. For those directly involved, the show was a springboard.

Could the formula be repeated? Was Young Scientists simply ‘of its time’ – never to be repeated? Promotion of school science is now more important than ever. Science competitions for young people still exist, but do they afford science the public exposure, status, and continuity offered by Young Scientists. Critics might say the format wreaked of elitism (the Grammar to Comprehensive school ratio would be interesting). Do schools have the time now? Would staff be motivated and willing? What about health and safety; PVC manufacture at 2 a.m.?

Despite the obstacles, the goal of broadcasting innovative school science – on prime time national television – with our greatest scientists in attendance – is a noble aspiration.

Could the UK public again be enticed to watch school kids do science? I like to think so.

Surely the greatest Young Scientist moment for Gateway was the winning of the European version in Iceland with the fingerprint scanner. I remember it in the display cabinet on the first floor stairwell outside electronics. It won the heat, the final and then Europe (or was it World).

The problem with the Polymer machine was simply that it was beyond everyday comprehension – why do it when ICI have huge factories to do the same. Where are the flashing lights and moving parts? 8 hours – the program only lasts 30 minutes!

Fingerprints were understandable; the need to match them was able to be expressed in layman’s terms. The machine used a count of the dark lines in the interference patterns of two images of fingerprints to determine whether the prints matched. The film about it demonstrated moiré patterns admirably through the interference patterns generated by the railings on motorway bridges as you drive under them. Never before had motorway bridges seemed so interesting (have a look up next time you pass under one)! The polymer machine had no meaning to the audience.

What school does this sort of thing now? You do not achieve the National Curriculum through engineering projects more that were more relevant to the present day degree level. Gateway (and other schools at the time) was special. The engineering was not aimed at any qualification – it was aimed at learning and bringing out the best in the students (or pupils as we preferred to be known). The result was interest and commitment (both amongst staff and students – teachers and pupils). We had fun and as a by-product – we learnt. Not all projects worked – the non hovering model hovercraft (the glow plug engined prototype went well – it didn’t translate to electric though), the pendulum clock that wouldn’t swing – but I remember the electric guitar, wooden toys for a home for disabled children and many others that were great. I still have my TV sitting on a wooden table made by a student at the school in Woodwork.

Whatever it was we did, it caught our imagination and we were better for it.

Gateway was nearly but not entirely unique – It was made so by the staff and pupils. I feel privileged to have gone there.

Its great that there is a UK Young Scientists of the Year competition today (the 2014 award was recently announced) but such a pity that the BBC isn’t enlightened enough to televise it as they did from the mid 1960s to the early 1980s. I was a member of team from Gateway School that won in 1970 with the fingerprint scanner and went on to jointly win the European competition in Eindhoven. I agree with the sentiment above, it caught the imagination of the school and only happened because of some amazing staff who passed on their enthusiasm to pupils. The team comprised David May, Mervyn Hall, Peter Kitson, Jeremy Hood and Peter Hall (myself). I often wonder if the video recording of the UK final still exists, if anyone from the BBC reads this perhaps they can find out. Who knows, they might even decide to revive the competition on TV!