Until last week, I’d only seen the Worcestershire town of Great Malvern from the air. Flying light aircraft in the nineties, one of my favourite sightseeing tours was to head out west from my local airfield near Stratford, turn south over Worcester racecourse towards the Malvern Hills, and watch the sun set over the waters of the Severn estuary.

The ‘Malverns’ are odd. An isolated stretch of peaks, nine miles long and 1394 feet at the highest point. Rising half way up the Eastern side, like a carpet pushed up against a wall, is the town of Great Malvern. In an aeroplane it’s a nice spot to practice steep-banked turns, while distracting your passenger with one of England’s greener and pleasanter views. We mostly got cloud and rain last week – so here’s a view in brighter conditions:

Amongst the famous folk associated with Malvern are C.S.Lewis and J.R.R.Tolkien, whose experiences walking together in the hills, it’s said, fed into their fantasy worlds. For sure, I can see how elves and dwarves might emerge from the cloudy scrumpy cider we sampled at the Unicorn pub – the authors’ favourite after-hike watering hole.

The composer Sir Edward Elgar was a local, and rests with his wife in nearby Little Malvern.

And the private school Malvern College gave many influential political, military, and media people their educational start – including journalist Jeremy Paxman; but not so many scientists or engineers it seems.

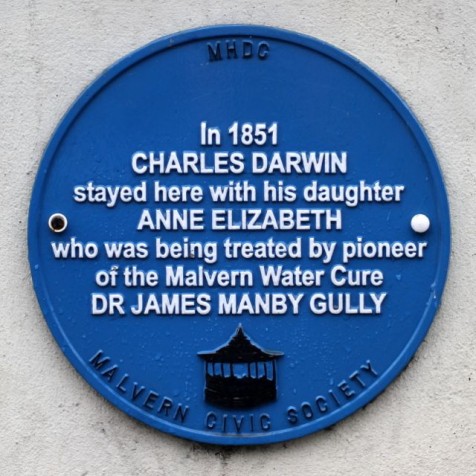

That said, it’s a scientist, Charles Darwin, that I associate most strongly with Malvern. A regular visitor from 1849, Darwin made the two-day journey to Malvern to partake of the town’s popular water therapy, hoping it might relieve the chronic vomiting and headaches that plagued him for much of his life (and caused some now think by Chagas’s disease1 contracted on his Beagle voyage to South America). He would later return with his seriously ill daughter Annie.

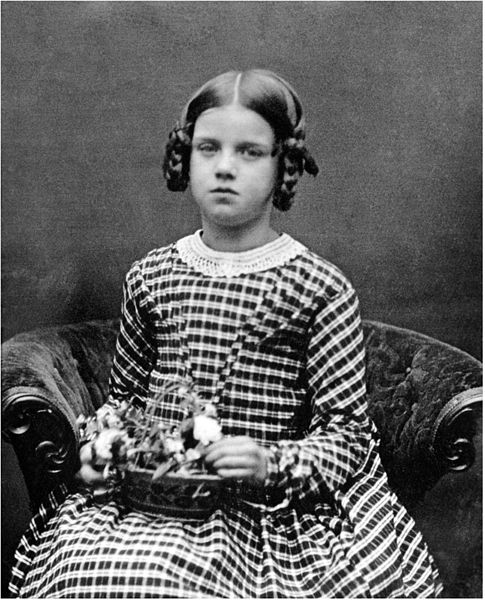

Ten year old Annie had weakened from scarlet fever over the previous two years, and, with her condition worsening, on 24th March 1851 Darwin made the trip with her to Malvern and Dr James Gully.

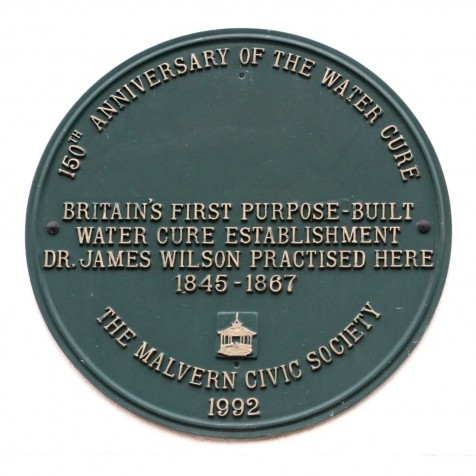

Pioneers of hydrotherapy, or hydropathy as they called it, Gully and his colleague James Wilson set up the first of several specialist clinics in the town. Like other spa towns in England, the geographic and economic growth of Malvern was largely driven by the perceived value of its natural waters.

Despite Gully’s efforts, Annie was beyond any water-cure, and Darwin was to leave her in Malvern, permanently, a month later. She died at their lodgings in Montreal House on the Worcester Road, and is buried in the grounds of nearby Great Malvern Priory – literally a stone’s throw from our hotel. Gully described Annie’s condition at death as a “Bilious fever with typhoid character”2; it’s now thought more likely she died from tuberculosis.

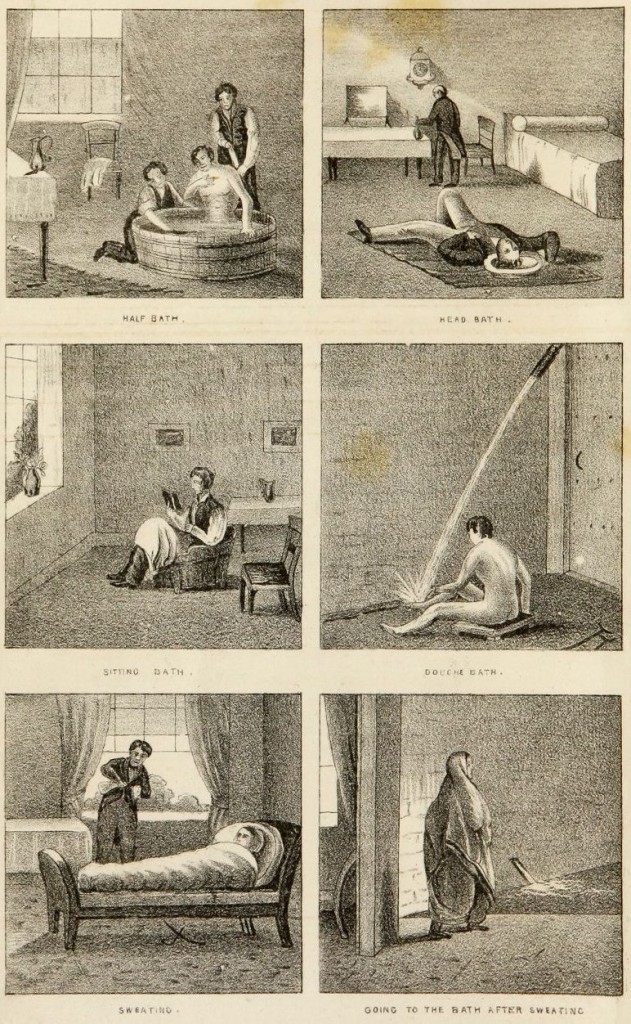

From a modern perspective, Gully’s water treatments were doomed to failure. The enthusiastic Gully might wrap a patient in wet sheets, subject them to heavy douches from above and below, or enroll them for a course of ‘spinal washing’.

The core water treatment might be augmented with anything from hill walks to homeopathy, to clairvoyancey, to what amounted to a light baking under oil lamps. Hydropathy’s enthusiastic adoption and questionable effectiveness groups it with the electrical and magnetic treatments popular with Victorian physicians at the time, eager to apply new insights on nature, however misguided, to human well-being.

Perceived benefits were most likely due less to the watery aspects of Gully’s therapy, and more to the generally healthy context of their delivery. Plain eating, abstention from alcohol, and daily exercise in a calming environment could do a lot for a bloated Victorian gentleman. But that didn’t stop Gully and like-minded advocates publishing elaborate treatises and supposedly affirmative case studies4 directly linking water therapy to the cure of all kinds of disease.

Darwin hung in with Gully’s ideas for years before concluding any benefit was limited and purely psychosomatic. He never bought into homeopathy, and seems to have gone along with the more spiritual add-ons from Gully’s palette to keep their relationship. Darwin was open to new ideas, but he always judged them against the standard of reason.

Darwin hung in with Gully’s ideas for years before concluding any benefit was limited and purely psychosomatic. He never bought into homeopathy, and seems to have gone along with the more spiritual add-ons from Gully’s palette to keep their relationship. Darwin was open to new ideas, but he always judged them against the standard of reason.

Annie was a special favourite among Darwin’s children, and her death took a lasting toll on his mental state. The poignant memorial he wrote to Annie is here at the Darwin Correspondence Project5

Annie’s story also formed the background to the movie Creation (my earlier review here), with Paul Bettany as Darwin, Jennifer Connelly as his wife Emma, and Bill Paterson as Dr Gully. The film, based on Darwin’s descendent Randal Keynes’s book Annie’s Box, is worth watching if you can forgive a bit of historical license-taking (for one thing, Darwin’s other children don’t age through a series of flashbacks involving Annie). Also, note that the town where they shoot the Malvern scenes, which I can now vouch has the feel of the place, is actually Bedford-on-Avon).

References

1. The Mystery of Darwin’s Ill Health. The Darwin Correspondence Project

2. Darwin, Desmond and Moore, Pub.Michael Joseph, 1991, p.384

3. Hydropathy, or, The water-cure: its principles, modes of treatment, &c., illustrated with many cases : compiled chiefly from the most eminent English authors on the subject. Shew, Joel, 1816-1855. New York : Wiley & Putnam, 1844. Link to text at U.S. Library of Medicine here.

4. The Water Cure in Chronic Disease. James Manby Gully, M.D., 1850, John Churchill, London

5. The death of Anne Elizabeth Darwin. The Darwin Correspondence Project

6. Note on the IHS monogram here at History from Headstones

Clairvoyance cartoon from George Cruikshank’s Table Book, 1845

I apologise for using your site for commercial purposes.

I have composed a piano piece called ‘Annie Darwin’. It can be downloaded for printing or read from tablets at http://www.usefulmusic.com/pieces/UD165. The download includes Charles Darwin’s private encomium in her memory. There is also a version adapted for flute and piano. The notation and audio can be sampled.

Randal Keynes thanked me on behalf of Charles and Emma for helping to keep Anniie’s memory alive.