Spending time in my original home town of Leicester last week was a chance to get better acquainted with the city’s recently recovered celebrity, King Richard III no less, at an exhibition in the ancient Guildhall. I also got to visit another of my favourite Leicester museums, The New Walk Museum and Art Gallery, which has its own bones to shout about.

Richard III

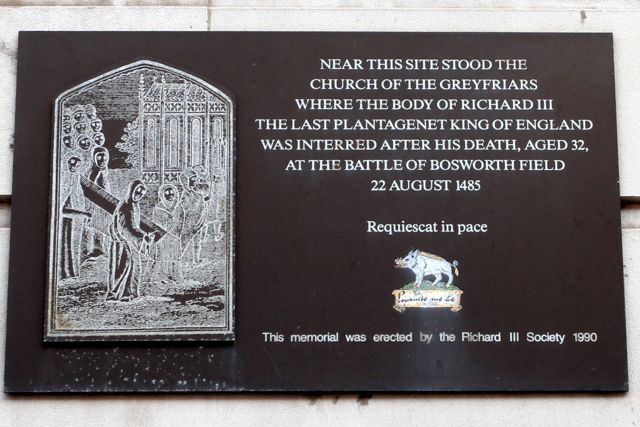

The search for Richard started in August last year, when the University of Leicester working with the King Richard III Society discovered and recovered a skeleton – everything but its feet – from a central Leicester car park: a car park that overlays the site of the former Greyfriars Priory.

With a barrage of forensic tests and historical interpretation brought to bear over several months, including a DNA match with a living descendant, the remains were finally declared the real deal in February this year.

An unlikely prospect made good for historians and archaeologists, I’m guessing I’m not the only one raised in the city for whom the find has a special fascination. I lived close to the King Richard’s Road; and as kids we visited nearby Bosworth Field, where Richard fell in 1485; and I can remember some rivalry with the local ‘King Dick’s’ school. The science labs where I studied for A-Levels were literally a stone’s throw from the burial site. I’m not suggesting Leicester folk spend all their time sat round thinking about history, but there’s always been a general awareness in the air.

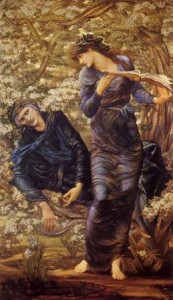

Richard’s character in life, unambiguously portrayed by Shakespeare as one of murderous villainy, is disputed – not least by the splendidly motivated Richard III Society. But there’s no doubting his popularity in death – not if the queues to the exhibition are anything to go by; I gave up on my first attempt and came back early the next day.

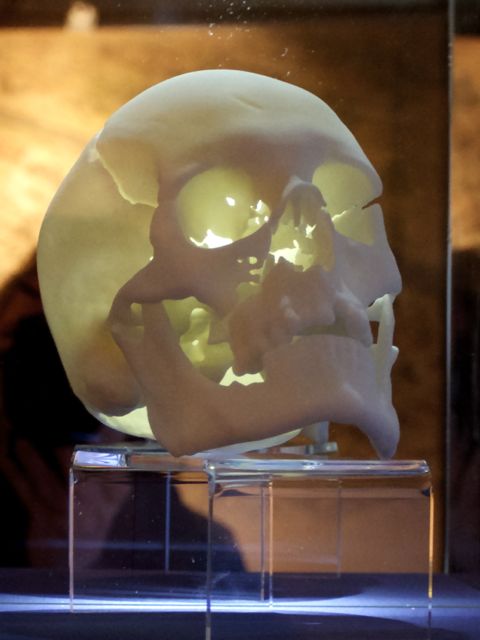

Rather than the real skeleton being on display, there’s a model of the skull and a light-table graphic representation of the bones. The side-on curved spine characteristic of scoliosis is clearly visible: doubtless the origin of historical reports/myths/exaggerations on Richard’s appearance and gait.

The suite of scientific tests used to characterise the remains included DNA Sequencing for identification, Radiocarbon Dating for age at death (1450-1538), Stable Isotope Analysis (tooth enamel) and Calculus Analysis (tooth plaque) for diet, health and lifestyle. The Leicester University team successfully matched mitochondrial DNA from Richard’s teeth with that from his living descendant Michael Ibsen. For more on the science, see Leicester University’s Richard III website.

New Walk Museum

Passing on Richard’s queue that first day gave me plenty of time to explore Leicester’s New Walk Museum and Art Gallery.

I’m spoilt for museums in London, but still have a soft spot for Leicester’s New Walk. It was the first museum I visited as a child: with an indoor goldfish pond and scary Egyptian mummies standing at the top of the stairs as you went in. The fish have gone, but the mummies are still there, better contextualised now in a special ancient Egypt exhibit. And overall they’ve done a great job of keeping up with the times.

On this occasion, supporting a special exhibition on DNA, I caught a lunchtime lecture on the human genome, by Dr Ed Hollox, a Leicester University geneticist whose talk focused on the genetic basis and geographical distribution of milk (lactose) intolerance.

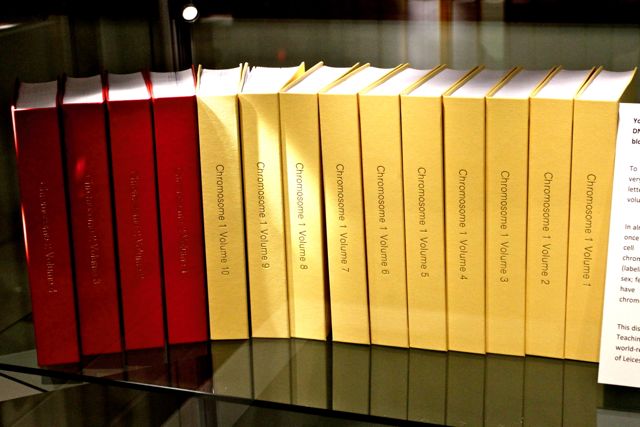

The Leicester group have also printed a 130 volume hard copy of the entire human genome – as a communication exercise in getting over the sheer size of the thing. The volumes, printed in tiny 4 point font, are on display at New Walk.

The Rutland Dinosaur

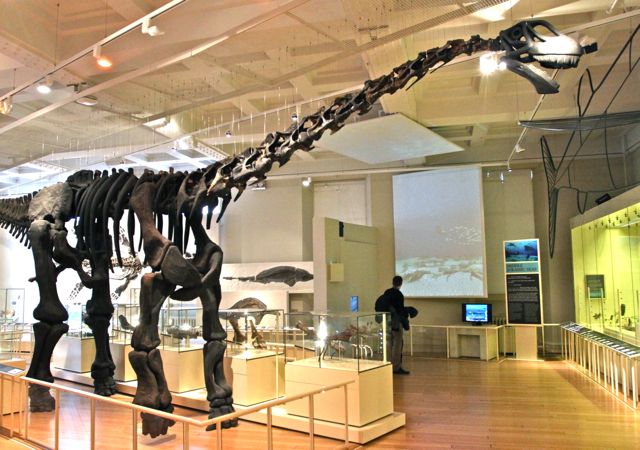

Back to the bones, and this c.168 million year old Ceteosaurus Oxoniensis , known as The Rutland Dinosaur.

The long-necked herbivore’s fossilised remains, recovered in 1968 from Great Casterton, Rutland – the county just East of Leicestershire – have a special claim as the most complete (about 40%) Sauropod found in the United Kingdom.

Connections

I’m not alone in my childhood memories of New Walk Museum. In this video, Sir David Attenborough, who hails from Leicester and stays close to the museum, recalls his early impressions. Incidentally, the chair he mentions, belonging to the giant Daniel Lambert, is now in Leicester’s Newarke Houses Museum – but that’s a different story.

Let’s not forget too that one of the oldest fossils in the world is kept at New Walk: the pre-Cambrian Charnia fossil, as featured in Attenborough’s First Life series (for more on that, see Return to the Land of Charnia).

All of which lets me finish on a nice obscure link, almost as unlikely as finding Richard III in a car park. Which is to realise the roof tiles from the Greyfriars Priory, recovered from the excavation and featured in the Guildhall exhibition, come from the very same Swithland slate quarry where Charnia was found.