Aspirin by any other name

Drugs have at least two names: a generic or scientific name, and then any number of manufacturers’ brand names for what is essentially the same thing.

So the generic names for two well-known painkillers are aspirin (acetylsalicyclic acid) and paracetamol (acetaminophen), but on Wikipedia you’ll find at least a hundred alternative brand names for paracetamol alone. My favourites are the cuddly ‘Panda’ and the bemusing ‘Europain’.

It’s done of course to differentiate a commercial product, or identify a mixture of drugs – like aspirin and caffeine in Anadin. But it hinders keeping track of particular chemicals that suit you, for a cold or whatever. Also annoying are brands that list different drugs by application under the same headline brand, especially when the contents vary between countries.

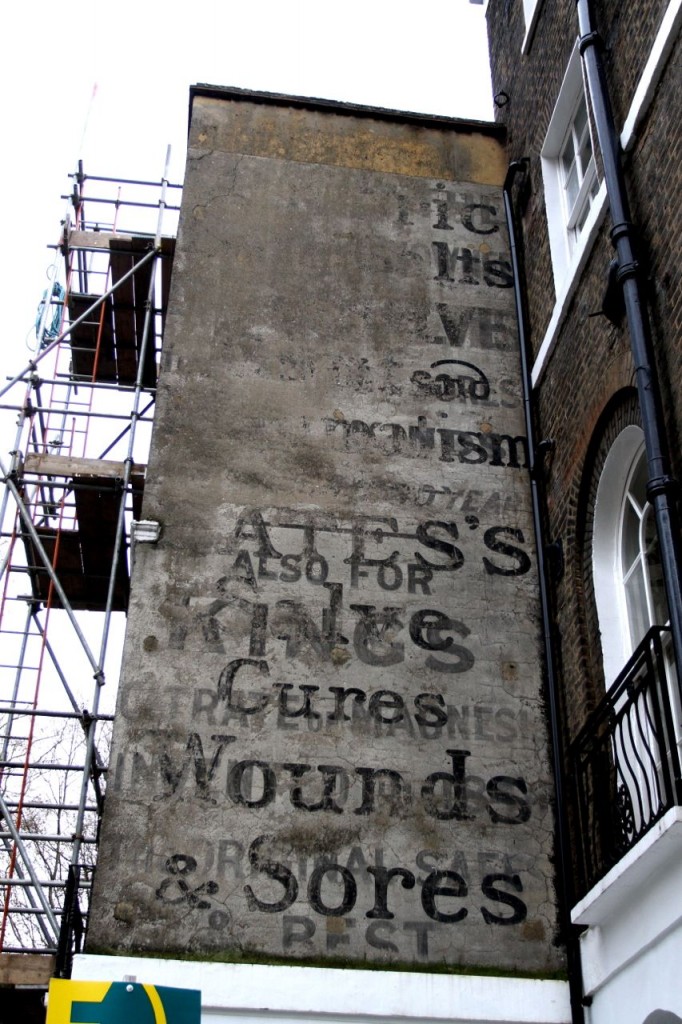

Ghost Sign

As much as I enjoy banging on about how brands can obfuscate choice and cloud rational decision-making – and not just in medicines – this post is really about that photo of a building above, that I took yesterday in Regent Square, London. It’s an unlikely and incongruous survivor. A wall covered in early hand-painted advertisements for medicines from a bygone age. It’s a ghost sign.

Probably Victorian, when salve and laxatives were all the rage, the full spiel for one of the products, ‘King’s Citrate of Magnesia’, made by Bates & Company, reads:

King’s Citrate of Magnesia

Invented in 1844

The Original Safest

& Best

W.W. King was a Liverpool chemist of mixed fortune. I found him listed twice in sources for 1851. First as a prize winner in the Catalogue of the Great Exhibition1 – for his ‘effervescent citrate of magnesia’, but also in Charles Dickens’s Household Narrative2 for that year, in his regular round-up of bankrupts.

Citrate of Magnesia induces a Motion

It was no secret that the article was entirely wanting in both citric acid and magnesia3

The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions, October 1, 1870

Magnesium Citrate, or Citrate of Magnesia, is still used as a uncontentious saline laxative and magnesium supplement. But it has a 19th century history that echos some of today’s complexities around drug names, descriptions, and branding.

We expect boxes and bottles of medicine to contain what the label says. But by 1870, a situation had developed where products labelled citrate of magnesia were more often than not found to contain a mixture of “tartaric acid, sugar, and carbonate of soda3 “. It made for a nice fizzy summer drink, but little else.

A hapless public bought the mis-named drug in spite of the unrealistically low street price; it wasn’t like they could slip on glasses and read the small print, because compulsory ingredients listing hadn’t been invented. That some brands, including King’s (of our wall fame), appeared to ship the real deal didn’t simplify the big picture.

A hapless public bought the mis-named drug in spite of the unrealistically low street price; it wasn’t like they could slip on glasses and read the small print, because compulsory ingredients listing hadn’t been invented. That some brands, including King’s (of our wall fame), appeared to ship the real deal didn’t simplify the big picture.

All this threatened the reputation of professional pharmacists, so, as reported in the October 1st 1870 edition of the Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions3 , some of them met to discuss a formal motion that would set things right – they hoped.

What’s in a name?

19th century Britons got their medicines from a variety of sources: via a doctor’s prescription, from an apothecary, chemist, or druggist, but also as commercial articles from the general store or local grocer. It’s like us going to the doctor, the pharmacy at Boots or RiteAid, or shopping at Tescos or Walmart. The difference is we get the same drug wherever we go, while for 19th Century folk it was more of a lottery. General commercial outlets were especially problematic – where unscrupulous quacks plied their mischievous trade of old. At worst, the more renegade outlets might be guilty of “applying definite chemical names to articles not having the composition thereby designated3 “.

The pharmacists thought renaming the product might be the answer, but that idea just got them in a mess. Do you call a thing what it is, or what it should be? Suggestions included “citrate of magnesia of commerce“, “citrate of magnesia so called” , “citrate of magnesia of pharmacy“, “granular effervescent citrate of magnesia“, or the more vague “granular effervescent salt“. Also names closer to the common composition, like “granulated tartrate of soda“; or “citro-tartrate of soda” – whose sponsor claimed special privilege because it was already listed in the British Pharmacopoeia (an early list of approved drug standards published in 1867).

In the end, relative sense prevailed, with options smacking of inaccuracy and deception, however pragmatic, being rejected in favour of scientific purity.

…this Conference, as representing and expressing the highest aims of pharmacy, ought to maintain a scientific purity and exactness in its nomenclature3

The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions, October 1, 1870

Not that everyone was behind an honest naming regime. It would confuse the public, said some, and open a Pandora’s Box of renaming obligations; hundreds of ambiguous favourites would be challenged: from ‘Salt of Lemons’, to ‘Seidlitz Powders’, to ‘Soda Water’.

From this strained conflict of pragmatism with scientific integrity a final motion was passed: a bit lame on specific actions, but a signal that professional pharmacists would not countenance inaccurate naming driven by commerce or tradition. At least for Citrate of Magnesia that is, by now firmly established as the tip of a misnomer ice-berg.

That this Conference is of opinion that the term ‘citrate of magnesia’ as applied to the ordinary granulated preparation of commerce is a misnomer, and ought to be discouraged as inconsistent with the true interests of pharmacy.3 (The final form of the motion)

The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions, October 1, 1870

Legislation

Motions from professional bodies are all well and good, but they’re not law. ‘Discouragement’ without legislation is toothless, and laws in this area had been slow in coming and often contested.

Earlier legislation, like the Apothecaries Act of 1815, defined standards and training for licensed apothecaries without actually outlawing unqualified practitioners, druggists, or quacks. The Medical Act of 18584 was more about regulating doctors, and explicitly excluded from its provision chemists, druggists, etc. involved in the sale of medicines (although it did action the earlier mentioned British Pharmacopoeia).

The Pharmacy Acts of 1852 and 1868, established under the auspices of the pharmacists’ own professional society – the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (est 1841) gave them powers to control drugs, and may explain why this was such an issue in 1870. But with those acts focused on poisons and dangerous drugs, legal actions against peddlers of mis-named versions of the pedestrian citrate of magnesia were brought under the more generic Food Adulteration Act (1860) or Adulteration of Food and Drugs Act (1872). Coincidently, these same legislations helped reduce the sawdust content of sausages, and alum and chalk in bread.

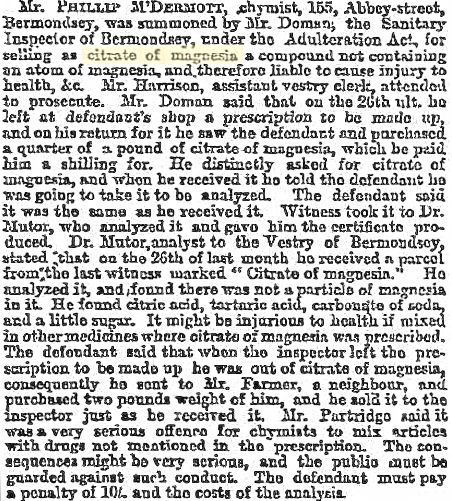

In this 1873 case, the defendant was found guilty under the Adulteration of Food and Drugs Act (1872), and fined £10 – about £1000 today – plus the cost of analysing his product:

Gradually things moved along, with further legislation on dangerous and controlled drugs appearing in the 1920s. The Medicines Act 1968 split drugs into the prescription, pharmacy, and general sales categories we have now. The naming of medicines in the UK is today administered by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), an agency essentially tasked with resolving the sort of issues our pharmacist friends were facing in 1870.

There’s no doubt controls over the naming and description of medicines has progressed massively since 1870. But with outstanding issues around the labelling and promotion of homeopathic products, and the classification and control of herbal remedies, the job’s far from over.

References

1. Official Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations 1851, Cambridge University Press, 2011

2. The Household Narrative of 1851, Ed Charles Dickens

3. The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions, October 1, 1870, P.275

4. Medical Act of 1858 (here at legislation.gov.uk)

Of Related Interest on Zoonomian

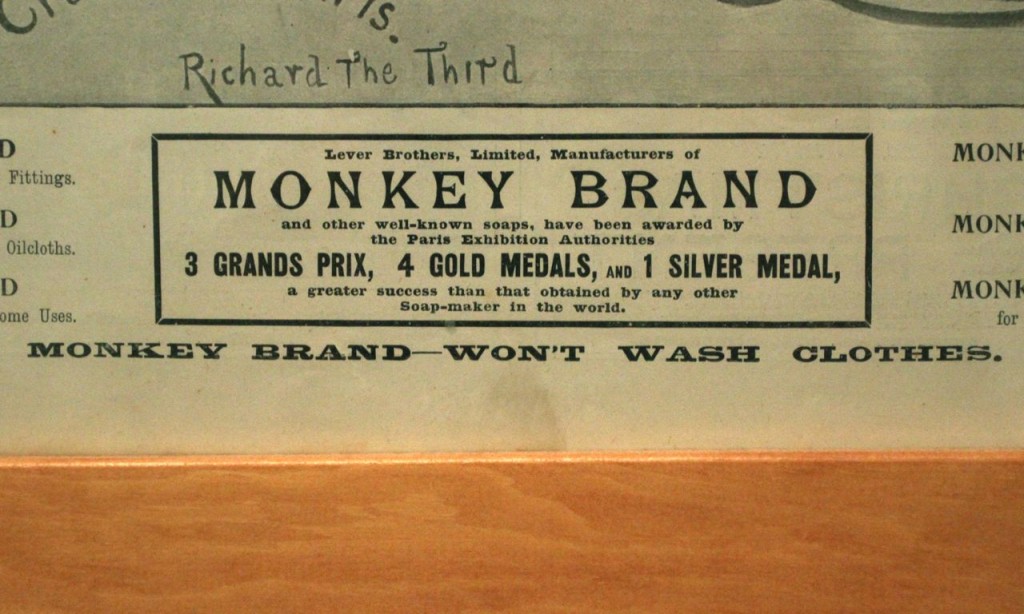

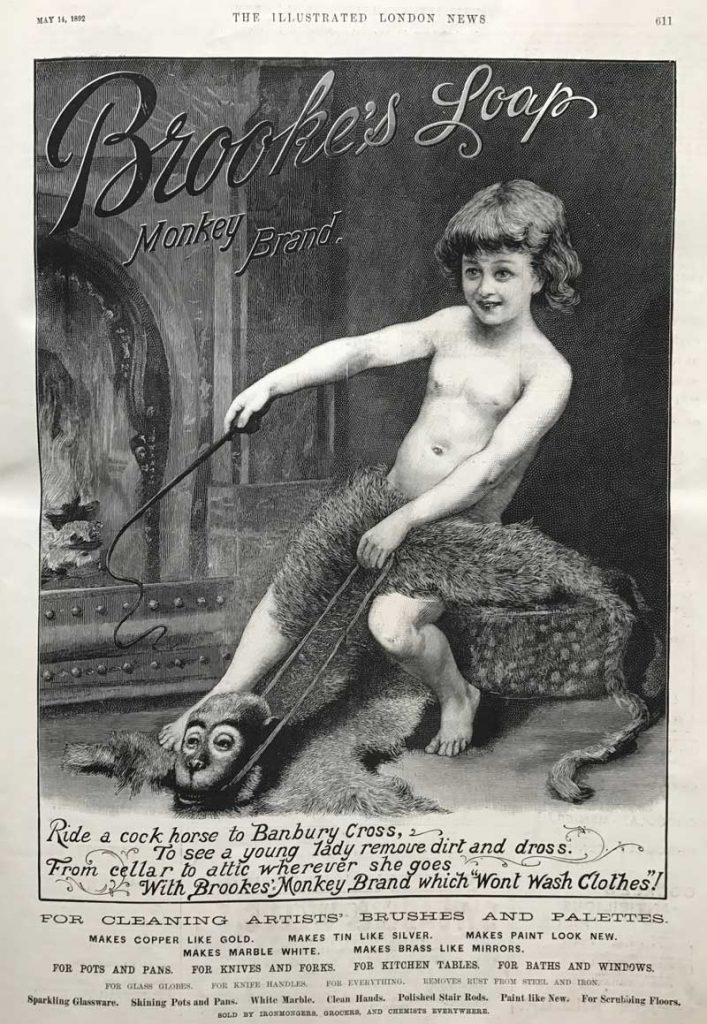

Monkey Brand Comes Clean (re: nineteenth century soap ads.)

Further Reading

More about Ghost Signs at Sam Roberts’s ghostsigns.co.uk

More medical ghostsigns at the History of Advertising Trust

Blogger Sebastien Ardouin says more about Bates & Co here.

More recent legal developments, more so for dangerous drugs, in: Shipman Enquiry, Fourth Report, Chapter 3 (pdf here)

More on the fight against food adulteration here at the Royal Society of Chemistry.