Tonight I joined the 2011 Darwin Lecture, with Sir David Attenborough speaking on ‘Alfred Russel Wallace and the Birds of Paradise’, organised and hosted by the Royal Society of Medicine in association with the Linnean Society of London.

Fresh back from a trip to Borneo – no less, the spritely 85-year-old was introduced by Professor Parveen Kumar, President of the Royal Society of Medicine, and Dr Vaughan Southgate, President of the Linnean Society.

Be it via the TV or lecture theatre, David Attenborough plays to full houses all the time, and this November evening was no exception.

Be it via the TV or lecture theatre, David Attenborough plays to full houses all the time, and this November evening was no exception.

His account of Wallace’s ocean voyage to the Malay Archipelago and pioneering observations of that unique group of theatrical show-offs: the Birds-of-paradise, made for an informative and fun evening – all the merrier thanks to a generous ration of film clips showing the birds’ unlikely courtship rituals.

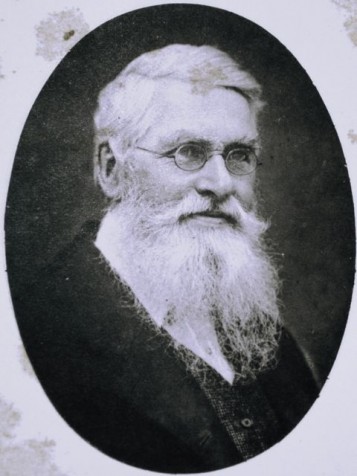

But the real take-home for me was Attenborough’s poignant re-telling of the Wallace-Darwin story: How the two independently arrived at that world-changing idea for the origin of species – natural selection – whereby only the better-adapted offspring of animals survive and pass on their qualities to a new generation.

Darwin had for years been working on his own version of natural selection from the comfortable surroundings of his home Down House, but had held back from publishing.

Then in 1858, Darwin receives a letter from Wallace, incapacitated with Malaria and holed-up in a shack on the Mollucas Islands of the Malay Archipelago. In it, he asks Darwin for an opinion on some ideas he’s had on the introduction of new species: ideas very similar to Darwin’s own.

Wallace’s communication is a bombshell. Yet for Darwin, the fear Wallace might publish first, pipping him at the post, is nothing compared to his horror of being branded a thief. So, after consultation with his scientific confidants, including Joseph Hooker but necessarily excluding the remote Wallace – Darwin’s camp decide a joint announcement of their common idea should be made at the Linnean Society in London, in the form of two short essays comprising Wallace’s note and a summary of Darwin’s work.

All goes to plan at the Linnean, and in due course Darwin publishes the full text of the ‘Origin of Species’ – with all the turbulent aftermath that comes with it. Wallace is comfortable with events, and pleased by the new associations he sees himself making in Darwin’s circle. He remains abroad, observing his beloved Birds-of-paradise .

Darwin, Attenborough said, made known his view that Wallace was capable – had he enjoyed Darwin’s own means – of producing the ‘Origin’ himself. Wallace on the other hand was more than grateful that the painstaking task of collation, supporting work, and documentation demanded of the masterwork had fallen to Darwin. In the lingo of the day, they’d reached a gentlemanly solution with no ill feelings all round.

Wallace produced much original work based on his observations of bird populations in the Malay Archipelago, which he captured in his book of the same name (The Malay Archipelago). Specifically, he identified the so-called ‘Wallace-Line‘ that runs between the islands of Bali and Lombok, separating two geographic regions whose animals Wallace found to be distinct and associated with either Australian or Asian origins. What he’d observed, without recognising it as such, was a product of moving land masses – or plate tectonics.

Related video:

David Attenborough talks about his fascination with birds of paradise (Nature Video)