In 1769, James Cook visited the island of Otaheite, or modern Tahiti, to observe the transit of venus.

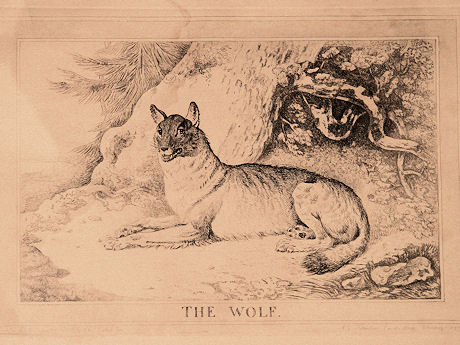

And these are the Otaheite Dog and Wolf, or at least 1788 aquatint renditions of them, made with some license if the awkward stance and anthropomorphic gaze are to be believed; but let that not distract from their story.

Drawn from life, engraved, and published by Charles Catton in his ‘Animals, Drawn From Nature and Engraved in Aqua-tinta‘, in 1788, the prints are technically interesting as representing the first use of aquatint for natural history illustration.

Catton started life as a coach painter, expertly representing animals in heraldry, and achieving the rank of coach painter to George III. Later in his career he helped document animals observed by adventurers like John White, who travelled to the South Seas in 1787, and whose ‘A Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales’ featured Catton’s picture of an Australian kangeroo. Like most artists at this time, Catton didn’t actually travel with the explorers, but worked from live and dead specimens sent home from the New World expeditions.

A contemporary advertisement for the journal contains a statement on accuracy that, applied to the Otaheite dog, is indefensibile by modern standards:

“The Public may rely, with the most perfect confidence, on the care and accuracy with which the drawings have been copied from nature, by Miss Stone, Mr. Catton, Mr. Nodder, and other artists; and the Editor flatters himself the Engravings are all executed with equal correctness, by, or under the immediate inspection of Mr. Milton.”

Despite their failings, Catton’s aquatints were an honest attempt to represent reality. What they lack, with the animals drawn dead and out of context, is any essence of the beasts: be that energy, poise, or sloth.

Catton’s Otaheite dog and wolf look similar, which is intriguing given John White made the same observation of their Australian counterparts:

“This animal is a variety of the dog, and, like the shepherd’s dog in most countries, approaches near to the original of the species, which is the wolf, but is not so large, and does not stand so high on its legs.

The ears are short, and erect, the tail rather bushy; the hair, which is of a reddish-dun colour, is long and thick, but strait. It is capable of barking, although not so readily as the European dogs; is very ill-natured and vicious, and snarls, howls, and moans, like dogs in common.

Whether this is the only dog in New South Wales, and whether they have it in a wild state, is not mentioned; but I should be inclined to believe they had no other; in which case it will constitute the wolf of that country; and that which is domesticated is only the wild dog tamed, without having yet produced a variety, as in some parts of America.”

Note the language: “approaches near to the original of the species”. Some concept of evolution clearly existed way before Darwin published his 1859 Origin of Species.

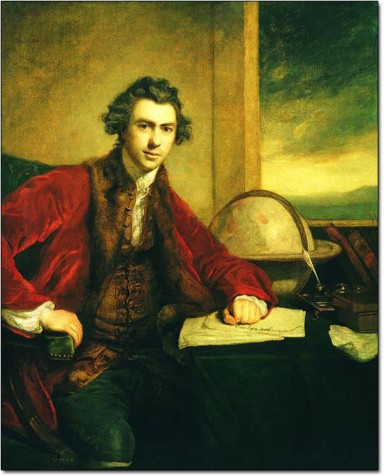

The London Natural History Museum’s beautiful ‘Voyages of Discovery’ describes the Pacific crossing made by James Cook, Sir Joseph Banks, and Sydney Parkinson on the Endeavour, including their visit to Otaheite. What it fails to mention is the Otaheite dog and, more importantly – how to cook it. For that we must turn to primary sources. In ‘A Journey of a Voyage to the South Seas‘, Sydney Parkinson describes how civilised Englishmen came to share the Otaheite locals’ penchant for tasty roast dog:

“These people also are fond of dog’s-flesh, and reckon it delicious food, which we discovered by their bringing the leg of a dog roasted to sell. Mr. Banks ate a piece of it, and admired it much. He went out immediately and bought one, and gave it to some Indians to kill and dress it in their manner, which they did accordingly. After having held the dog’s mouth down to the pit of his stomach till he was stifled, they made a parcel of stones hot upon the ground, laid him upon them, and singed off the hair, then scraped his skin with a cocoa shell, and rubbed it with coral; after which they took out the entrails, laid them all carefully on the stones, and after they were broiled ate them with great goût; nor did some of our people scruple to partake with them of this indelicate repast. Hav-ing scraped and washed the dog’s body clean, they prepared an oven of hot stones, covered them with bread-fruit leaves, and laid it upon them, with liver, heart and lungs, pouring a cocoa-nut full of blood upon them, covering them too with more leaves and hot stones, and inclosed the whole with earth patted down very close to keep in the heat. It was about four hours in the oven, and at night it was served up for supper: I ate a little of it; it had the taste of coarse beef, and a strong disagreeable smell; but Captain Cook, Mr. Banks, and Dr. Solander, commended it highly, saying it was the sweetest meat they had ever tasted; but the rest of our people could not be prevailed on to ate any of it.”

“These people also are fond of dog’s-flesh, and reckon it delicious food, which we discovered by their bringing the leg of a dog roasted to sell. Mr. Banks ate a piece of it, and admired it much. He went out immediately and bought one, and gave it to some Indians to kill and dress it in their manner, which they did accordingly. After having held the dog’s mouth down to the pit of his stomach till he was stifled, they made a parcel of stones hot upon the ground, laid him upon them, and singed off the hair, then scraped his skin with a cocoa shell, and rubbed it with coral; after which they took out the entrails, laid them all carefully on the stones, and after they were broiled ate them with great goût; nor did some of our people scruple to partake with them of this indelicate repast. Hav-ing scraped and washed the dog’s body clean, they prepared an oven of hot stones, covered them with bread-fruit leaves, and laid it upon them, with liver, heart and lungs, pouring a cocoa-nut full of blood upon them, covering them too with more leaves and hot stones, and inclosed the whole with earth patted down very close to keep in the heat. It was about four hours in the oven, and at night it was served up for supper: I ate a little of it; it had the taste of coarse beef, and a strong disagreeable smell; but Captain Cook, Mr. Banks, and Dr. Solander, commended it highly, saying it was the sweetest meat they had ever tasted; but the rest of our people could not be prevailed on to ate any of it.”

And that about wraps it up for the Otaheite Dog. Yummy.