An Unfortunate Accident

Modern revolvers have a mechanism that keeps them from firing accidentally if knocked or dropped. Before that, savvy owners learned to carry their weapon with an empty chamber under the hammer. Californian real-estate developer Clarence Austin was not among them.

Picture Austin, one May day in 1909, setting off on a peaceful fishing trip. He parks up his vehicle, ready to meet a connecting streetcar. Running late, he hurriedly unloads his gear, casually throwing a blanket roll to the sidewalk. As the roll strikes the ground, a forgotten pistol consealed in its folds discharges. The bullet rips through Austin’s knee, and lodges, somewhere, in his leg.

Picture Austin, one May day in 1909, setting off on a peaceful fishing trip. He parks up his vehicle, ready to meet a connecting streetcar. Running late, he hurriedly unloads his gear, casually throwing a blanket roll to the sidewalk. As the roll strikes the ground, a forgotten pistol consealed in its folds discharges. The bullet rips through Austin’s knee, and lodges, somewhere, in his leg.

“I am shot!” Austin perceptively exclaims – according to the Los Angeles Herald1.

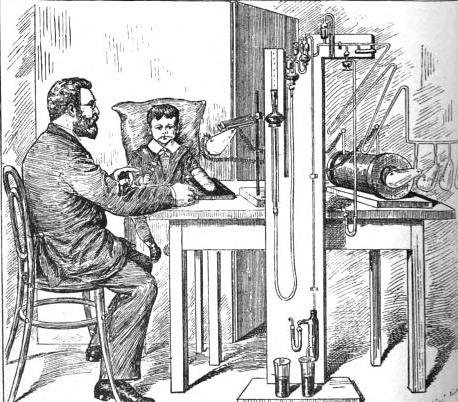

Bystanders rally and Austin is ambulanced home. A doctor arrives, and, with a strange electrical apparatus that emits invisible rays, locates and removes the offending slug. Austin Clarence will live to sell real-estate another day.

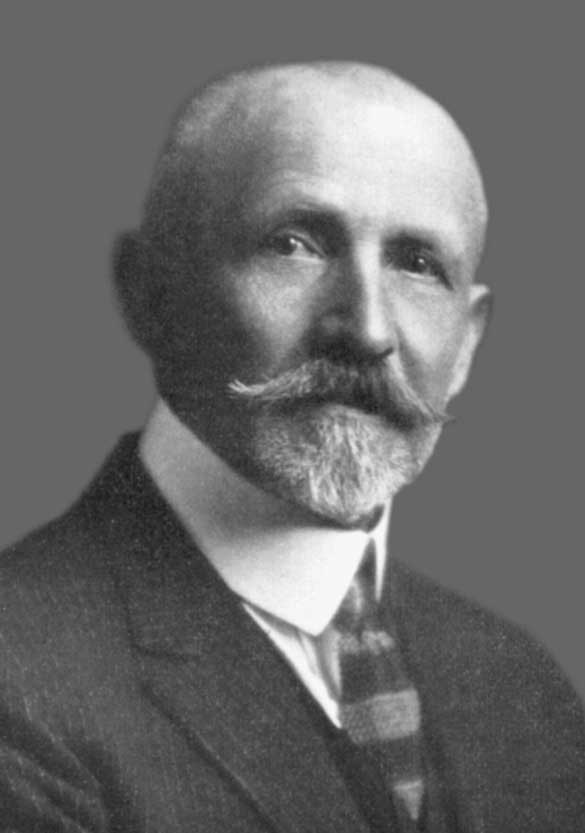

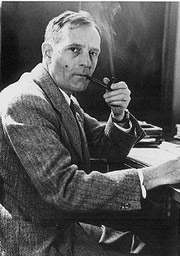

As luck would have it, Austin had picked the best possible neighbourhood west of the Rockies to shoot himself in – for his attending physician was Dr Adalbert Fenyes (1863-1937): M.D., neurologist, celebrated entomologist, all-round gentleman scientist, and – importantly for Austin – one of the very few early practitioners in medicinal X-rays. Fenyes lived in a city 10 miles northeast of Los Angeles, a place that Einstein once compared to nothing less than paradise: Pasadena.

Here in Pasadena it is like Paradise. Always sunshine and clear air, gardens with palms and pepper trees and friendly people who smile at one and ask for autographs.

Albert Einstein, 19312

I discovered Fenyes on a recent visit to the Pasadena Museum of History. Custodians of the Fenyes legacy, the museum is situated at the site of the former Fenyes Mansion at 170 North Orange Grove (now 470 West Walnut Street).

While not quite an A-Lister in the Einstein league, Adalbert, taken together with his accomplished artist and businesswoman wife Eva, give us a fascinating glimpse on a bygone age: a lost vignette of turn-of-the-century intellectual life in a city whose attraction for talented people, and especially scientists, persists. Fenyes also opens the door on two other Pasadena scientists I particularly admire: the astronomers George Ellery Hale, and Edwin Hubble: who, like the Fenyes’s, supported their city as well as their science.

Gentleman Scientist

There are no direct British parallels to Fenyes – aristocrat son of a Hungarian Count, but he may be close to a Charles Darwin or John William Strutt – Baron Rayleigh (of Argon discovery and Rayleigh Scattering fame): gentlemen scientists with broad interests and the independent means to work to their own agendas.

Fenyes trained as a physician in Austria, and was doctoring in Egypt when he met American heiress Eva Scott Muse – while on her Grand Tour .

After a spell in Chicago, where Adelbert studied X-ray procedures, in 1896 the couple settled in Pasadena, moving to the new $20,000 mansion in 1907.

Multi-faceted Fenyes M.D. ran a physician’s office downtown – specialising in neurological problems – while Fenyes the entomologist wrote scholarly papers, built an insectorium in the mansion grounds, and travelled to collect specimens4 ; a two month trip to Mexico yielded no less than 10,000 beetles5. Fenyes’s beetle collection is now with the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco.

Fenyes discovered several new genera and species within the order Coleoptera (beetles). Always the gentleman, here is one he named after his wife:

While Adalbert’s insect research appeared in learned journals, the bug-hunting trips became the stuff of society page gossip, alongside the movements of movie stars and business tycoons. Fenyes repaid the attention, albeit to the favoured few, with popular lantern slide talks on his beetle research – including samples – to Pasadena’s exclusive Twilight Club (all male) and Shakespeare Club (all female). The civicly framed “Insects and Their Value to the Community”(1904) 6 betrays Fenyes’ skill as a science communicator, tuning into his business-minded audience. Even insects had to pull their weight in those industrious times.

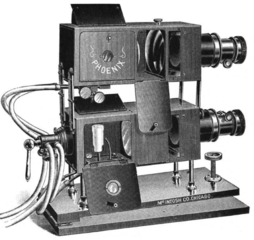

Röntgen Rays

Within a year of Wilhelm Röntgen’s 1895 discovery of X-rays, and Michael Pupin’s method of imaging developed the following year, medical applications started to appear. Fittingly for our story, one of Pupin’s early exposures, or skiagraphs, shows a hand riddled with self-inflicted buckshot7. In the case of Clarence Austin’s leg, Fenyes was able to see the location and orientation of the bullet, and identify cloth fragments carried into the wound. By replacing the photographic plate with a fluorescent screen it was possible to operate ‘live’, the surgeon’s skeletised hands and instruments visible hovering over the patient’s wound (Gillanders8 ). Portable equipment run off car batteries was in use by 18999.

A prominent researcher in the field, Fenyes led a session on ‘X-ray therapy’ at a 1903 meeting11 of the Southern California Electro-Medical Society in Los Angeles, alongside sessions on ‘Galvanism’ and ‘Static Therapy’. Fenyes studied the effects of X-rays on the kidneys and other organs, and for the treatment of non-malignant skin disease like acne and eczema 12 , personally escaping the worst of the radiation burns and illness that seriously injured or killed many contemporary practitioners. When he moved to Pasadena, he had one of the rare X-ray machines shipped to his home – possibly the equipment used on Austin.

If Pasadena had any single founder, it was George Ellery Hale

Kevin Starr in his history of California13.

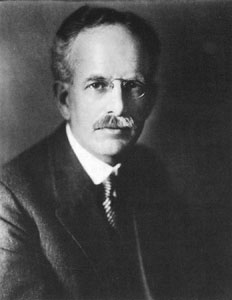

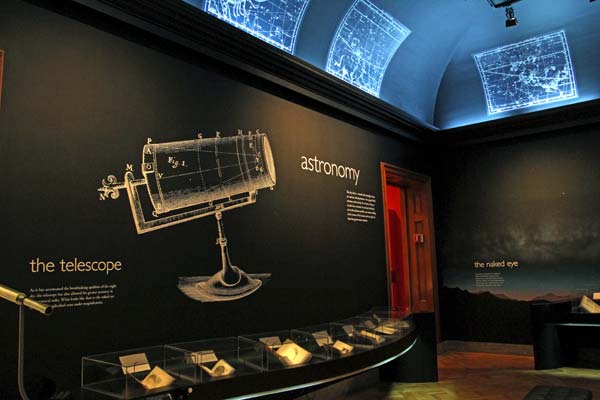

Our next urbane utopian is Chicago born George Ellery Hale (1868-1938): best known – at least among astronomers – as the instigator, designer, and builder of the world’s greatest astronomical observatories and telescopes.

Inspired by his first sight of the Lick Observatory as a young man on his California honeymoon, Hale ‘made-it-so’ for the 40-inch Yerkes refractor in Wisconsin, the 60-inch and 100-inch reflecting telescopes on Mount Wilson, and the 200-inch ‘Hale’ reflector on Mount Palomar.

Inspired by his first sight of the Lick Observatory as a young man on his California honeymoon, Hale ‘made-it-so’ for the 40-inch Yerkes refractor in Wisconsin, the 60-inch and 100-inch reflecting telescopes on Mount Wilson, and the 200-inch ‘Hale’ reflector on Mount Palomar.

Possessed since childhood of a high-energy passion and interest in all things, Hale explored, studied, experimented, and built machines in his laboratory workshop: basically doing all the fun stuff kids are arguably over-protected from today (anyone whose father bought them a steam-driven lathe for Christmas, as Hale’s did, is bound to turn out right in my book).

As the calendar flipped into the twentieth century, 32 year old Hale, already an established solar astronomer with the invention of the spectroheliograph under his belt, was keen to progress research on stellar evolution started at the Yerkes Obervatory. Hale had in mind a series of newer, bigger, and more capable solar instruments, the siting of which, in terms of atmospheric conditions, would be critical. In 1903, his global scouting mission reached Pasadena.

At first, the test observations looked hopeless. From ground level, a shimmering heat from the baking dessert distorted the Sun’s image. But tests at the top of Mount Wilson, a 5700 foot peak in the San Gabriel Mountains overlooking the city, told a different story. Here, where extensive tree cover insulated the ground and muffled the disabling thermals, conditions were perfect. Mount Wilson commanded a World Class view of our nearest star14.

And so the love affair with Pasadena began, when in 1904 Hale took up the directorship of the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory. Dull, wintery, climates depressed Hale; Southern California would do just fine.

Hale’s contribution to astronomy is well known. Less well known, even I suspect among some Pasadenans – is that the city’s California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Huntington Library, Civic Center, and a host of other organisations, institutes, and clubs, only exist because of Hale’s energy and commitment.

No one could be associated with Hale without falling at once under the charm of his vivid and inspiring personality

Walter S Adams, Biographical Memoir15, 1939

Comfortable in the intellectual gentility of Pasadena society, Hale immediately slipped into a circle of friendship, influence and wealth where he would progressively share his vision of Pasadena as nothing less than a ‘New Athens’ of the West. His influence on millionaire industrialist Andrew Carnegie had secured Mount Wilson, but there were always new telescopes to be built. Hale kept potential sponsors and the general public informed of his work through a series of popular talks, including – one year into the project – an upate to the good ladies of the Shakespeare Club:

Prof. George K. Hale, the famous director of the Mount Wilson solar observatory, left a driving snowstorm this evening at the observatory and came

down to Pasadena to give his first lecture in this city. It was at the instance of the Shakespeare Club, and the beautiful auditorium of the clubhouse was crowded for the welcome occasion. Prof. Hale spoke in an informal manner of the building of the observatory, the difficulty of transporting the instruments and material and of the non-technical progress of the work of investigation….

In his recent photographs of the milky way from the top of Mount Wilson, Prof. Hale remarked that the wonderful photographs indicated in a very definite way the remarkable transparency of the atmosphere in the vicinity of the observatory.

Los Angeles Herald, 190516

The Los Angeles Herald has it slightly wrong here, as Hale’s first Pasadena outing was a year earlier on 28 January 1904, with a talk on ‘The Evolution of the Stars’ to the Throop Institute17: the educational facility Hale would gradually transform and in 1920 see formally renamed as the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Hale also gave popular talks to the Friday Morning Club in Los Angeles and most likely, the Twilight and Valley Hunt Clubs of Pasadena where he was a member.

Four years later in 1909 and things have moved on a bit. Adalbert Fenyes, on his way home from an X-ray session with a certain Clarence Austin, looks up (we suppose) and sees a shiny white tower on the mountain crest: shiny, because the paint on Hale’s new 60-foot solar telescope tower – completed in the Fall of 1908 – is barely dry.

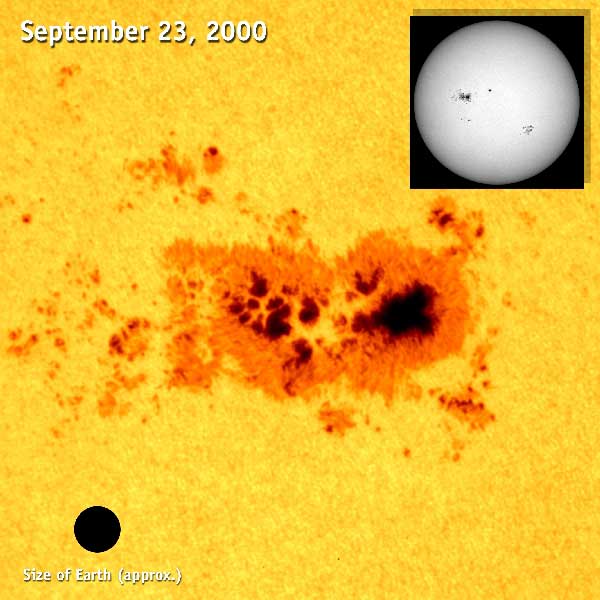

The ‘Snow’ horizontal solar telescope, borrowed from Yerkes, was already at the site; but this new instrument made possible Hale’s most important discovery: that the sun has magnetic fields18 and their association with sunspots. For a description of how he did it, see here (USC history page).

Both the 60-foot, and a 150-foot instrument from 1912 are still used for research today.

Solar telescopes follow the Sun with a moving plane mirror, or coelostat, often mounted at the top of a tower. The light is directed through a stationary lens to a focus below ground, where, because it’s not being slewed around on the end of a long tube, all manner of equipment can be assembled, including Hale’s spectroheliograph to analyse the Sun’s image at specific wavelengths of light. At Mount Wilson, Hale took these ideas to new extremes of scale and sophistication.

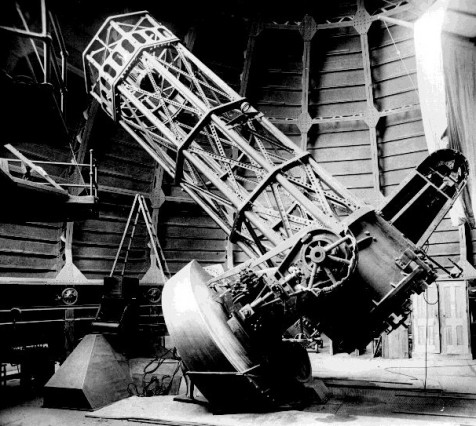

All in all, 1908 was a busy year. The solar tower was completed, but so too was the even more ambitious 60-inch reflecting telescope – easily the world’s largest, and this time for night-time use. Bearing in mind the Sun appears 400,000 times brighter than the Moon, and 13 billion times brighter than the next brightest star, Sirius, you need a much larger lens or mirror at night to collect enough scarce photons to make objects visible. Hale trudged his heavy 60-inch diameter glass mirror, and a 150 tons of supporting telescope steelwork, up Mount Wilson by mule train and a primitive mountain truck.

The lead up to the delicate mirror’s installation on 7th December 1908 must have been a particularly stressful time for Hale, and may go some way to explain why on the 19th November he got arrested following a high-speed motorbike chase with the Pasadena Police Department19,20: an offense that cost him $10. (1908 was also a bad year for the “nervous attacks” Hale suffered from for much of his life25.) But it was all worth it, and on the night of 20th December Hale was rewarded with an early Christmas present: the best naked-eye view of the Orion Nebula anyone had seen up to that point.

When Colonel Griffith J Griffith visited Mount Wilson in 1908, and looked through the new 60-inch, the views inspired him to fund the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles’s Griffith Park, proclaiming:

If all mankind could look through that telescope it would change the world!

Colonel Griffith J Griffith, 1908

Today, visitors can look through a 12-inch refractor telescope at Griffith for free, or hire the 60-inch on Mount Wilson at $900 for a half-night or $1700 for the whole night.

1908 was a challenging year for Hale in the roadcraft department. As well as the high speed run in with police in November, he had already suffered a collision with a motor vehicle in March that year: in which he “made a flying leap and landed safely in the road. The front part of his motorcycle was ground to pieces under the wheels of the car.”21

Private road vehicles were popular, available, and accessible to monied Pasadenans. Electric vehicles were favoured by ladies en route to the opera, keen to avoid soiling their gowns with horse muck or the oil and swarf of the internal combustion engine. Eva Fenyes drove one: on one occasion mounting the pavement and virtually inverting the car through a plate glass window22.

The big telescopes aside, I particularly like Hale’s attitude to: (a) investment in science, and (b) the amateur’s role in science. His approach to investment, not just in money, but in time and recognising the need for a long view, is still relevant in the age of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), and, indeed, super-telescopes. His enthusiastic support for amateurs resonates with the burgeoning trend for so-called Citizen Science. Writing in 1905, with the challenge of equipping Mount Wilson ahead of him, Hale is uncompromising on what it takes to make progress in scientific research:

A man of science must so direct his efforts as to secure the largest results not within a single month or a single year, but within the entire period of his activities. He can thus afford to devote much time and effort to details of construction, if these promise sufficient advantage in the end. He must work years, if need be, to secure such means of investigation as appear to him needful.

The Development of a New Observatory, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific23, Vol. 17, No. 101, April 10, 1905

Hale’s equally unrestrained enthusiasm for amateur science positively bubbles over in his essay Work for the Amateur Astronomer24, where he recalls his own evolution from schoolboy experimenter roots:

But neither in limited or unlimited resources nor in association with public or private laboratory do we find the criterion that marks the amateur. Nor is he to be mistaken for the dilettante of the popular imagination. The amateur is in fact a true lover of knowledge for its own sake, one who works because he cannot help it, swept on by a passion for research which he attempts neither to explain nor to curb, an enthusiasm which carries him over obstacles too high to be surmounted by the perfunctory student or the man without zeal. To the sane enthusiast, whether his talents be large or small, great advances are possible. An impelling interest, even if backed by only a very slender stock of knowledge, may accomplish more than all the learning of the schools...

The passion for research springs early, and the boy of twelve may already feel within him the desire to add to the world’s knowledge. He consults his books, and is fascinated by the experiments they outline. Who can forget his thrill of excitement when the bubbles of oxygen, issuing from the heated retort, rose one by one thru the water-filled bottle, inverted over its tank! The delicious possibility of an explosion (realized all too often with prematurely ignited jets of hydrogen!) and the proud consciousness of actually venturing into the field of the original investigator, are experiences to be felt but not described. Then there was the winding of the first induction coil, the anxious test of the length of its spark, and the dim realization that here was an instrument of research applicable in many fields…

“In recent years, as I have pushed with larger and larger telescopes into the depths of space, I have often been forced to confess that the astronomer never beholds sights more wonderful than those which a drop of ditch-water, on the stage of the cheapest microscope, will afford to any boy.

WORK FOR THE AMATEUR ASTRONOMER, 191624

All good things, and people, come to an end. His mother feared he would burn out early, but in the event Hale put in a very respectable innings before his health, and his psychological demons, caught up with him. Hale suffered a serious nervous breakdown25 in 1921, which led to a wind-down and eventual full resignation from the Mount Wilson directorship. When Hale started out in astronomy, his ever-encouraging father built him an observatory equipped with a 12-inch refractor. Now, in his retirement, he commissioned his own solar observatory for private research – in Pasadena of course.

Unlike the solar telescopes, the 100-inch was a laviathan of the night, with two and a half times the light gathering power of the 60-inch reflector Hale installed in 1908. It would remain the world’s largest telescope until Hale outdid himself one final time with a 200-inch instrument on Mount Palomar (operational in 1948, he never saw it completed). And the arrival of the 100-inch, as one element of a perfect storm of capability, knowledge, and inspiration that was about to redefine our concept of the universe, is the perfect cue for our last résident du paradis : Edwin Powell Hubble.

Receding Horizons

Thanks to Carl Sagan, Neil deGrasse Tyson and Brian Cox, it’s no great mystery to most of us that we live on a planet, near a star, in one of many galaxies that make up the expanding universe.

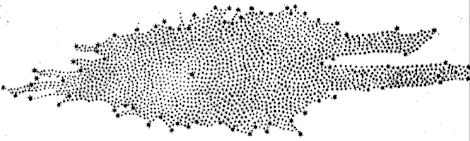

But in 1919, when 30 year old Edwin Powell Hubble (1889-1953) returned from the First World War to work for George Hale at Mount Wilson, that was not the case. William Herschel, as early as 1785, estimated the shape of the galaxy by counting the number of stars he could see in different directions. But he had no idea about size, and assumed the fuzzy patches between the stars – he called them nebulae – were all contained inside the one collection. Hubble was not the first to question this picture of the universe. Dark lanes in the spiral shaped Andromeda nebula looked something like the dark lanes in our own Milky Way: so were we looking at something like a copy of ourselves? And the red-shifted spectra of some nebula suggested they might be separate entities. But solid evidence was lacking, and it would take Hale’s 100-inch telescope, recent discoveries about variable stars, and Hubble’s conviction and skill – a perfect storm – to prove we are part of something much larger.

Using the 100-inch telescope, Hubble could for the first time resolve individual stars in the Andromeda and other nebulae. And by measuring the brightness and periodicity of Cepheid Variables – special ‘standard candle’ stars whose absolute brightness and periodicity Henrietta Leavitt had in 1908 showed to be related, he could calculate the distance of both the stars and their containing nebula.

In 1923, Hubble did exactly that for Cepheid variable Hubble V1 in Andromed. In a delicious example of restrained scientific under-statement, the magic distance number: 285,000 parsecs, or 929,100 light years, appears almost lost in the text of Hubble’s 1925 address to the American Astronomical Association26 (reminiscent of Crick and Watson’s first paper on DNA in its down-play of implications). Our galaxy is 100,000 light years across, so Hubble had, figuratively, expanded our universe by a factor of ten – and that based on Andromeda, which, cosmically speaking, is virtually on top of us. We now think the universe is 150 billion light years across. Hubble went on to measure the red shifts of many different galaxies, which showed these ‘island universes’ to be moving away from each other at a rate proportional to their distance. Not only was the universe larger than we ever imagined – it was expanding too. Hubble’s photographs of Andromeda, with the Cepheids he measured marked in his own hand, are on display in the Huntington Library.

Hubble’s announcement may have set the scholarly hearts of American Astronomical Association members racing, leaving the popular scientific press of the day to translate for the rest of us – as in Science News-Letter‘s enthusiastic headline27:

Sky Pinwheels Are Stellar Universes 6,000,000,000,000,000,000 Miles Away

The Science News-Letter, Dec. 1924

I make it 5.5 x 1018 miles, but close enough. Of Hubble’s observations of a 700,000 light year distant cluster in Sagitarius, the Daily Princetonian28 declared:

Another Universe Exists Beyond Telescope Reach

Daily Princetonian, January 1926

Again, not entirely accurate, but I guess people got the idea. I dutifully drove past Hubble’s house on Woodstock Road, San Marino, where he lived from 1925 till his death in 1953. Designed by Joseph Kucera in 1925, it is the only National Historic Landmark in Pasadena’s neighbour city. It’s also situated in a very nice spot – handy for the Huntington Library, and looks very little changed from earlier photographs. (And today well out of the reach of all but the wealthiest early-career scientists.)

I guess out of the three: Fenyes, Hale, and Hubble – Hubble’s ghost has had the best popular run, mostly down to the space telescope named after him.

But Hubble’s original work, that literally expanded our horizons a billion-fold, is not forgotten, and in 2010 was specially honoured when the telescope bearing his name was turned to once more monitor the brightness of Hubble variable V1 in Andromeda. When the data were analysed, the period of variability derived from the modern measurements was found to be in agreement with the historical values. Or to put it another way, while you are more likely to be run down by a Tesla than a Waverley today, the light curve, like much of Pasadena, has barely changed.

But Hubble’s original work, that literally expanded our horizons a billion-fold, is not forgotten, and in 2010 was specially honoured when the telescope bearing his name was turned to once more monitor the brightness of Hubble variable V1 in Andromeda. When the data were analysed, the period of variability derived from the modern measurements was found to be in agreement with the historical values. Or to put it another way, while you are more likely to be run down by a Tesla than a Waverley today, the light curve, like much of Pasadena, has barely changed.

References

1. Real Estate Dealer Accidentally Hurt. Los Angeles Herald, May 7, 1909

2. Albert Einstein, U.S. Travel Diary, 1930-31, p.28 via Einstein Papers Project

3. Mrs Fenyes and the Movies. Home Town Pasadena

4. Fenyes Colioptera (beetle) collection is kept at the California Academy of Sciences Entomology Collection Highlights

5. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 35, Number 266, 24 June 1908

6. Twilighters in Session. Los Angeles Herald, Volume XXXI, Number 183, 30 March 1904

7. Pupin’s slide is on display at the Huntington Library, San Marino

8. The Roentgen Rays In Bullet Extraction. I. L. G. Gillanders, British Medical Journal, Vol.1, No 1950 (May 14, 1898), p.1252-1253

9. Portable X-ray powered from car. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 601, Number 185, 3 April 1899

10. The New Photography. Arthur B. Chatwood, Pub. Downey & Co. 1896

11.’Electricity in Medicine – Southern California Society Will Meet This Afternoon’. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 30, Number 239, 2 June 1903

12. Southern California Practitioner, Vol 18. 1903 P541

13. The Dream Endures: California Enters the 1940s. Kevin Starr, Oxford University Press, 1997.

14. May Locate Giant Telescope on Summit of Mount Wilson. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 31, Number 115, 22 January, 1904.

15. Biographical Memoir of George Ellery Hale, by Walter S Adams, National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoirs, Vol.21, fifth memoir.

16. Important Work at Observatory. Prof. Hale Shows Progress of Investigation. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 33, Number 51, 21 November 1905

17. Illustrated Lecture at Throop. Los Angeles Herald, Volume XXXI, Number 122, 29 January 1904

18. On the Probable Existence of a Magnetic Field in Sun-Spots. Hale, G. E., Astrophysical Journal, vol. 28, p.315, 1908ApJ….28..315H

19. Hale Arrested for Speeding. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 36, Number 50,

20 November 1908 20. Hale Pays FineLos Angeles Herald, Volume 36, Number 54, 24 November 1908

21. Dr Hale Injured by Fall From Motorcycle. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 35, Number 172, 22 March 1908

22. Car Crash. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 33, Number 112, 21 January 1906

23. The Development of a New Observatory, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Vol. 17, No. 101, April 10, 1905

24. WORK FOR THE AMATEUR ASTRONOMER, George Ellery Hale, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Vol. 28, No. 163 (April, 1916),pp. 53-61 Pub. The University of Chicago Press.

25. Hale’s “Little Elf”: The Mental Breakdowns of George Ellery Hale. Sheehan, William; Osterbrock, Donald E., Journal for the History of Astronomy, 05/2000, .93

26. Hubble, Edwin P., “Cepheids in Spiral Nebulae,” Pubs. Amer. Astr. Soc. 5, 261-64 (1925); reprinted in Observatory 48, 139-42 (1925).

27. ‘Sky Pinwheels Are Stellar Universes 6,000,000,000,000,000,000 Miles Away’, The Science News-Letter, Vol.5. No.191, Dec 6, 1924, pp.2-3. Pub. Society for Science and the Public.

28. Daily Princetonian, Volume 46, Number 170, 25 January 1926

Location Map

View Pasadena Science in a larger map Further Reading Includes examples of Eva Fenyes painting, article in Hometown Pasadena Journey to Palomar video: Includes background on Hale, more on the 200-inch Palomar telescope, and a look to the future and the planned 30 metre telescope.