I guess at times we all put up a mask in public. We might even have a bit of a dark side kept under wraps most of the time. But there’s something extra-disturbing when our heroes show a side to them we never knew, especially when it’s at odds with the comfortable stereotype they’ve come to represent.

Take doctors for example: helpful, trustworthy folk, blessed with skills in beneficent care and correcting surgery. Yet Lars Tharp, talking about Hogarth and medicine at the Foundling Museum yesterday, reminded me of at least one medical man with a shadow over him, and a dark side literally demarcated by the geography of his home.

Those who have read Wendy Moore’s biography The Knife Man will know I’m talking about John Hunter – traditionally tagged with the strap-line ‘Father of Modern Surgery’ – as he doubtless was.

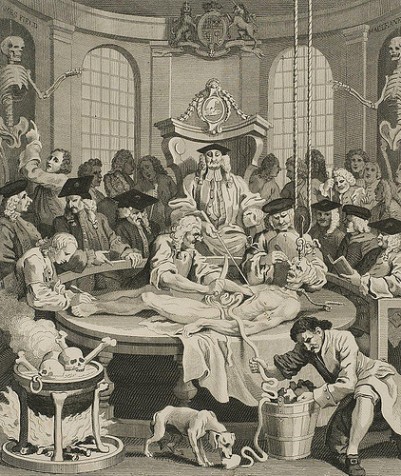

That was almost an accolade he could celebrate in his own lifetime, within the genteel and elegantly decorated reception rooms of his Leicester Square mansion. Yet the learning behind Hunter’s reputation wasn’t gained in his salon, but in the less well publicised back rooms and tiered operating theatre, fed by grisly subjects for anatomy arriving all too timely through the back entrance on shabby Castle Street.

Hunter had cleverly bought the house onto which his Leicester Square residence backed, and built his museum and operating theatre between the two – creating separate worlds.

Not surprisingly, scholars credit Hunter’s situation as the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel Jekyl and Hyde.

Incidentally, Hunter was also in his day the top expert on venereal disease, and it’s thought likely he intentionally infected himself with syphilis via his penis for the sake of research. So despite his unconventional sourcing strategy for bodies, at least he wasn’t selfish.

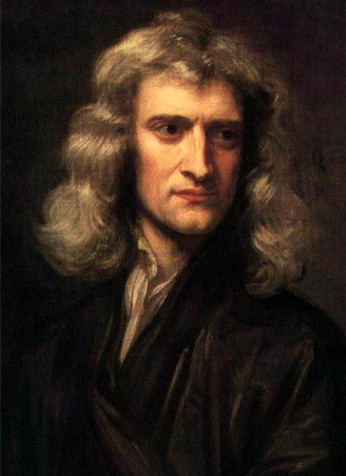

Tharp mentioned Hunter only in passing, but a further remark he made puts me in mind of another scientist with a dark side – Isaac Newton, no less.

The Newton we imagine sitting under a tree, watching apples drop, benevolently ruminating his prisms and calculus, is a far cry from the Master of the Mint Isaac Newton, who doggedly pursued forgers and clippers (they cut bits of valuable metal off coins to sell) to a horrifying death at the Tyburn gallows. (There’s an excellent account of Newton’s life at the mint in Thomas Levenson’s Newton and the Counterfeiter).

Tharp’s case didn’t implicate Newton personally, but dealt with the particularly harrowing story of a mother found guilty of clipping and awaiting execution at Newgate, pleading with the Foundling Hospital to take care of her child.

Her child was saved, but she went on to be burned at the stake all the same; think about that next time you deface the coin of the realm steadying a wonky table leg with a 2p piece (do your own research as to the true present-day hazard of this heinous sin).

So what other scientists’ dark secrets have come out through history to muddy their fantasy image.

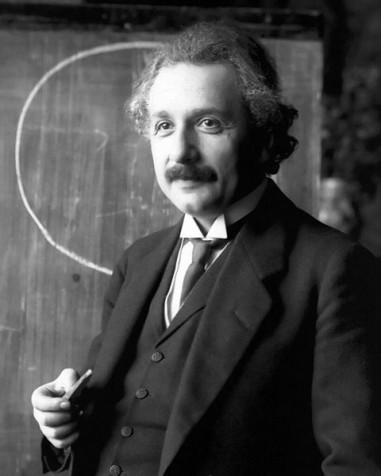

There’s Einstein: a nice old guy who wouldn’t harm a fly, right? Wrong – at least as far as his family were concerned. Einstein cheated on his wife, set out unreasonable conditions for their marriage to continue, and paid little attention to his children. And while we accept Einstein was human like the rest of us, that’s somehow more information than we want to hear.

There’s often a conflict in the minds of scientists who choose to do war work: like building bombs, weapon systems, or other enablers of physical destruction; and there’s still a debate around the social responsibility scientists should bear for the outcomes of their work (although I sense it’s more settled that scientists should indeed feel that obligation). Closer to home, as a humble chemical engineer in peacetime 1980s Britain, I lacked the opportunity or temptation to get conflicted in that way, but, for sure, the most interesting and rewarding jobs for my physics and electronics buddies were defence related. I guess Robert Oppenheimer, reluctantly self-styled Destroyer of Worlds and leader of the atomic bomb Manhattan Project, is the text-book example in this category, although if there’s one guy truly qualified for the E-word on that team it’s probably giddy hydrogen bomb fan Edward Teller.

Fritz Haber is another example. The Haber process for making ammonia was hugely useful and constructive in the manufacture of fertiliser. But Haber’s dark association with poison gas manufacture for Germany in the first world war – captured in Tony Harrison’s play Square Rounds – caused his vilification to this day.

It’s an imperfect comparison, but as a scientist whose work ultimately saved millions of lives – through the food produced using ammonia fertilisers, but at the cost of lives lost to gas and explosives, Haber shares some common ground with surgeon William Hunter. How much faster did surgery move along because society, with a bit of convenient blind eye turning, allowed Hunter access to the bodies he needed? (Related to this idea, I’ve most recently been intrigued as to where we’d be had some of the more questionable early twentieth century work on brain surgery not gone ahead – as it for sure wouldn’t today.)

What this comes down to is that scientists are just people after all: some pretty nice, some about alright, and some pretty rotten.

On a brighter note, having multiple facets to your sparkling intellect can also be a good thing.

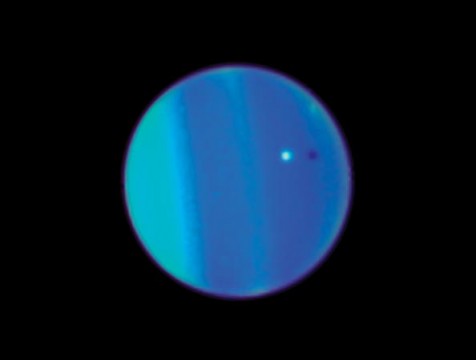

Astronomer William Herschel’s (1738-1822) tale of confliction is a relatively happy one that I think made his life more fulfilling.

Herschel discovered Uranus and built fabulous ground-breaking telescopes. But he was also a professional organist and competent composer, whose first love – and bread and butter for much of his life – was music.

And it stayed with him; Herschel’s cheery ‘Echo Catch’ was performed at the pleasure gardens in Bath only a year before he discovered the mysterious seventh planet. For other good stuff Herschel got up to, see this earlier post.

I’m sure there are loads more examples of scientists whose dark side has come to light through some sordid revelation. But these are the ones who sprang to mind; maybe I’ll add more later. Feel free to volunteer candidates – especially if they’re still living.

Right! Two in morning. Now where did I put my cape and sword-stick.

References & further reading

1. The Knife Man, Wendy Moore, Bantam Press 2005

2. Newton and the Counterfeiter, Thomas Levenson, Faber & Faber, 2009

3. The Other Side of Albert Einstein, Physics World, 2005

4. Square Rounds, Tony Harrison, Faber & Faber, 2003

5. The Georgian Star. Michael Lemonick, Atlas, 2008

6. Article on Fritz Haber here at Smithsonian.com