The last thing I expected at a history talk with Stephen Fry was a discussion on the relative merits of rationalism and empiricism. But that’s what we got for part of the time at the Harper Collins Annual history Lecture at the Royal Institute of British Architects last month. And for some reason, the topic’s stuck in my head.

A rush to rationalism?

The difference between rationalism and empiricism essentially turns on the degree to which we draw on the evidence of our senses in creating knowledge.

Fry’s comments were a warning through illustration of over-dependence on apparently rational decisions. As the conversation moved to the fall of the Berlin Wall, Fry made the point that while it seemed rational to liberate Eastern Europe with the flourish, rapidity, and completeness now symbolised by the dismantling of the wall, that process also had unforeseen consequences in the form of unprecedented crime and corruption.

Fry likened it to the activation of a sleeping cancer one might find in a patient from Oliver Sacks’s book Awakenings. These negative developments had been kept in check only by the strictures of the former regime, and were now – in some quarters – the cause of discontent and a call for a return to a more certain past.

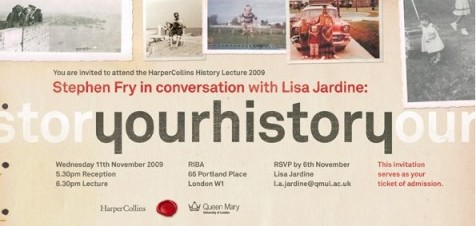

- Stephen Fry in conversation with Lisa Jardine at RIBA (Photo: Sven Klinge)

It’s hard to know whether an empiricist approach would have predicted the unlooked for outcome, or whether the experience of Eastern Europe has informed China’s more recent and ongoing transformation. But when looked at in this way, the Chinese process, whereby economic liberation moves ahead of relaxation in political and social controls, might not be all bad. For while the West finds elements of the process distasteful, what greater chaos might be unleashed under a less managed regime?

Yet at an emotional level, attacks on rationality can grate, especially with scientists and technologists. I bristled when Fry likened over-zealous support for rationalism to belief in religion. Was this the same Stephen Fry whose debate trounced the Catholic Church, and who regularly shares platforms with the likes of Richard Dawkins? But rather than rejecting rationalism, I believe he made a valid point: that it is too easy to assume a rationalist approach in all situations – however complex – when sometimes the abstract premises from which we deduce knowledge for decision making are just not up to it.

A palette of reason

Moving on, but with an eye to Fry’s sentiments, there seem to be an awful lot of reasonable sounding words out there: like ‘rational’, ’empirical’, ‘evidence-based’, ‘logical’; and indeed – ‘reasonable’. Whether in the context of drugs policy, climate change, faith schools, or whatever; these words sit like so many pigments on a palette of reason, wielded by individuals and governments alike, to convince us – and themselves – that a particular course of action carries some special sanction. But why do the same words frequently lead to misunderstandings and angst?

It seems to be down to definition and interpretation. Boiling our list down to rationalism and empiricism (subsuming ‘evidence-based’ into empiricism and logic into rationalism) the dictionary definitions and learned philosophical commentaries leave plenty of scope for confusion.

The Compact Oxford English Dictionary defines rationalism as:

‘the practice or principle of basing opinions and actions on reason and knowledge rather than on religious belief or emotional response’, and empiricism as

‘the theory that all knowledge is derived from experience and observation‘

which seems pretty clear. But the Oxford Pocket English Dictionary muddies the rational water by including philosophical and theological interpretations that flex the definition of rationalism to a form no scientist could agree with. It seems scientific rationalism is just one brand. I’ve really no idea what to make of the theological interpretation given as:

‘the practice of treating reason as the ultimate authority in religion’.

but it put me in mind of this quote from the current Pope, relayed in this interview by the Vatican astronomer Guy Consolmagno, and equally confusing to my concept of rationality:

“religion needs science to keep itself away from superstition“

No wonder there’s confusion

This all goes some way to explain why scientists find themselves at odds with the government on issues like drugs policy and the recent Nutt affair.

Professor David Nutt led a committee advising the British Government on drugs policy, until he was sacked for speaking publicly in a manner the Home Secretary judged inconsistent with his position. The sacking blew up into a huge debate about the role of scientific advisors and their advice, what they can say when, and the way scientific evidence is used in a politically cognisant, but surely still rational, decision making process.

Some of our reasonable words appeared in the popular press; such as ‘empirical‘ in this Daily Mail piece by A.N.Wilson:

Evan Lerner has argued the technical inaccuracy of this statement that leaves us nowhere to go. If empirical facts are no good, decision makers must be following a rationalist stance or some ‘third way’ unbeknown to philosophers. But I’d argue the politicians are just following a brand of rationalism that suits their purpose; it’s just not a scientific one. And when A.N.Wilson goes on to invoke the R-word:

he’s right; anyone who doesn’t comply with the scientific definition of rationality is demonised. Personally I’d like the scientific definition to be universally accepted, but while there are powerful constituencies who benefit from and delight in wooliness defended as realism or flexibility (politicians, theologians, dictionary compilers), I can’t see it happening.

Likewise, the only kind of rationality under which a discussion on the virtues of faith schools makes sense is one that allows ethical and metaphysical propositions (e.g. is there a god). Moreover, we’re left with politicians working up a drugs policy using an ethics-based ‘political rationality’, and an education policy that recognises and values a ‘religious rationality’.

Unfortunately, the transparency being called for concerning when and under what circumstances this flexing of scientific rationalism happens, also threatens politicians with the anathema of exposing less visible agendas traditionally played close to the chest.