The film Creation went on general release in the UK today, and as I’m just back from a lunchtime viewing, here are a few thoughts on the movie while it’s still fresh in my mind.

To cut to the chase: enjoyable film, with great performances from Paul Bettany as Charles Darwin and Jennifer Connelly as his wife Emma. I’m giving it 4 out of 5 stars.

Very odd start though. I arrived at 12.10 for a 12.15 showing and had the theatre entirely to myself. By 12.30 ish, when the ads were over, the final audience had grown to six people. I know most folk can’t just knock off for the afternoon, but I found it surprising all the same; clearly not one for the pensioners.

I’ve made a point of not reading most of the Creation reviews already out there; just one or two quickly once over. So I’m relatively untainted but sufficiently informed to pick up on some of the obvious criticisms.

One of those criticisms has concerned the film’s factual accuracy. But as few viewers will have read the various biographies and letters, it strikes me that the emphasis should be more on identifying only serious material misrepresentations – and overall I don’t believe there are any (an exception is Huxley’s character – read on).

I was pleased to see certain events included: the failure to ‘civilise’ the Fuegan kids, the water cures, the influence of Hooker & Huxley, Darwin’s animosity with his local church, and Wallace’s letter.

At times though, I felt some incidents and issues had been slotted in because they had to be there – as if the director had a check list of ‘leave that out and the Darwin aficionados will play hell’. That’s how I felt about Huxley’s appearance anyhow. Arguably, Huxley came in to his own in the affairs of the Origin only after its publication – exactly the point at which this film ends. But the filmmakers have done T.H. an injustice all the same; the take-away impression of the man is just wrong. Richard Dawkins wasn’t overjoyed with the portrayal, and I can see why; the character is out of kilter with the historic record, and may as well have worn a ‘new atheist’ sash. (I find New Atheist a silly term; what is an old atheist? – Quiet?). Intellectually, the portrayal is overly one-dimensional and aggressive. Physically, Toby Jones is too short to portray a man whose height and presence in reality matched his intellect. They got Hooker’s whiskers down to a tee, so why not Huxley?

The core narrative revolves around Charles’s relationship with, and thoughts about, his daughter Annie. I don’t know the actor who played Annie, but she has an obvious future in Hollywood. We don’t get to know the other children anything like so closely as we do Annie; and the intellectual, as well as emotional, bond between Annie and Darwin is particularly well developed. There is something of the co-conspirator about Annie – a sense of allegiance lacking in Emma until a reluctant appearance in the final scenes.

The various ghost sequences have been criticised, but again, I just saw these as a device to illustrate Darwin’s pre-occupation. I don’t think he actually ran about the streets chasing his dead daughter (but please correct me if you know different).

All the themes in the movie ultimately link back to the Origin and what it stands for. One of the more human incarnations of that influence is the Emma – Charles relationship. Here I’d liked to have seen Emma’s philosophy explored a little more – even if the detailed story-line were credibly fabricated (biographers do this all the time). I guess we can never know someone’s innermost thoughts on life, the universe, and everything – no matter how many letters we read; but I felt the middle ground that our two protagonists must have found could have stood a little more exploration.

And never mind the movie, I find this theme of different fundamental philosophies within a relationship fascinating. I wonder how many couples today mirror Charles and Emma? This is a personal blog, so I can say that I would, for example, find it challenging at best to live with a partner who I knew was going to hell. That said, I have friends in atheist/Christian marriages who appear to get on just fine.

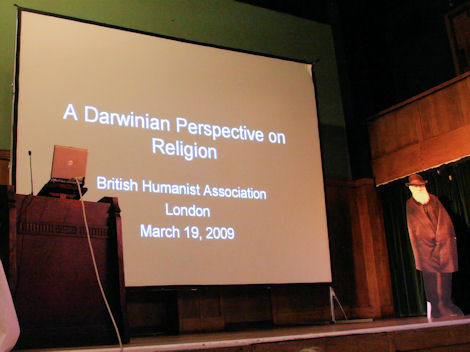

Which brings us to the big issue: is there a conflict between science and religion? Back to Huxley, I suspect the director intentionally set him up as the fall guy on this score; he can safely be hated for his total lack of religious accommodation early on in the film. Hooker does pop up now and again to reinforce the atheist line (the word is not used – nor is Huxley’s later derived ‘agnostic’), but never with Huxley’s brand of enthusiastic venom.

So what will a religious person make of this movie? After all, wasn’t it the possible religious reaction, and associated reduction in box-office $, that was behind the recent stink over US distribution (the film now has a US distributor).

There is nothing in Creation more offensive than a portrayal of the facts of evolution as they were understood in Darwin’s day. And Darwin’s encounter with Jenny the orangutan, which is beautifully represented in the film (well it’s not really acting is it) leaves little more to be said on the question of our own evolution. I’m not about to dive into a lengthy science-religion debate, suffice to say my position is that there are elements of religion as defined by some that are – on the evidence – incompatible with some definitions of science; and that the science-religion debate is an important one with practical consequences for us all.

God’s official in Creation, the local vicar, is played by Jeremy Northam. In one memorable scene, Northam tries to comfort Darwin in his torn anguish, which only sparks a sarcastic tirade from Darwin on the delights of the God-designed parasitic wasp larvae and the burrowing habits of intestinal worms. Northam’s sincerity and Bettany’s losing his temper are both convincing.

I live within an hour’s drive of the real Down House, and know it pretty well. While the house in the movie was not Down, the exterior feel – with large bay windows and patio doors opening to the garden captures the right flavour.

The study has a similar feel to English Heritage’s reproduction of the real thing at Down – even down to Darwin’s screened-off privy. Likewise, the lounge and dining room, while never visible in wide-shot, have an attractive homely ambiance. The village road and church scenes are consistent with the feel of the real Down.

It’s not the end of the world, but a sandwalk scene was noticeable by its absence. The sandwalk for those who don’t know it is a gravelly path leading into the woods near Down House. I tend to imagine Darwin pacing down the sandwalk, under the trees or sheltering from the rain; to be sure – it’s a nice spot for thinking.

To wind up, this movie contains all the main factual, scientific, cultural, and emotional elements I associate with Darwin in this important period in his life. Issues around the compatibility of science and religion are met head on through illustration (if a little caricatured) rather than tedious debate, and we get to see the human, sensitive and fragile side of a scientist.

There is plenty here to enjoy in the theatre, but also much to take home and mull over – with your partner perhaps :-).

Go see it ! 4/5.