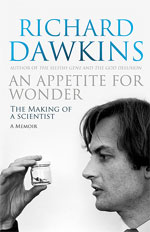

I’ve just finished Richard Dawkins’s self-narrated audiobook of An Appetite for Wonder: The Making of a Scientist, where, introducing a task given to him by his research supervisor Niko Tinbergen, related to nature versus nurture aspects of animal behaviour, he makes special mention of the White-crowned Sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys nuttalli). As it happens, earlier this year I caught this native of North America pecking at a fig.

Is behaviour built in at birth – innate and instinctive? Or is it learned from experience? One way ethologists, who study animal behaviour, try to answer such questions is to compare the behaviour of subjects artificially deprived of normal early life learning opportunities with those raised in their natural habitat.

In the case of birdsong, tests on Sedge Warblers show they automatically know their song without ever hearing the tune from another bird. As Dawkins puts it, they ‘fumble’ towards the final song, trying different sounds and sequences from which they assemble a correct version; so the process is innate: it’s all ‘nature’.

The White-crowned Sparrow also teaches itself to sing its unique song by fumbling and picking out the good bits, but, unlike the Sedge Warbler, it needs to have heard its song from another White-crowned sparrow in early life; it needs a prompt to know where it’s going – so to speak. As for many animal behaviours, including human behaviours, the White-crowned Sparrow’s song is the product of a nature-nurture combo of innate and learned influences. Dawkins wonders what similar early life deprivation experiments, within ethical bounds, might be made to study the human condition.

You can hear the White-crowned sparrows song here at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.