You’re a young 33, with an already impressive scientific career under your belt, and – although you only suspect it – a spectacular future ahead of you. Within 10 years, you’ll be elected President of the Royal Society.

But in November 1811, you’ve got something else on your mind.

How exactly would Humphry Davy (he of Davy Lamp fame among many other achievements) impress the first true love of his life – the beautiful widow and heiress Jane Apreece ?

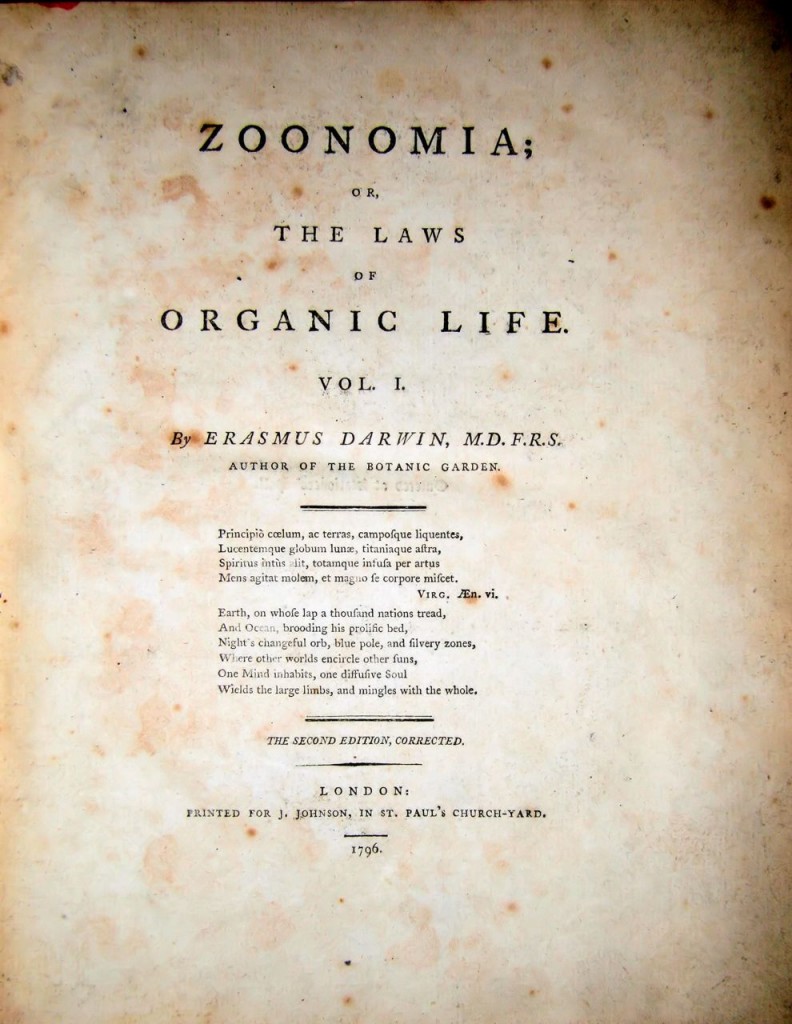

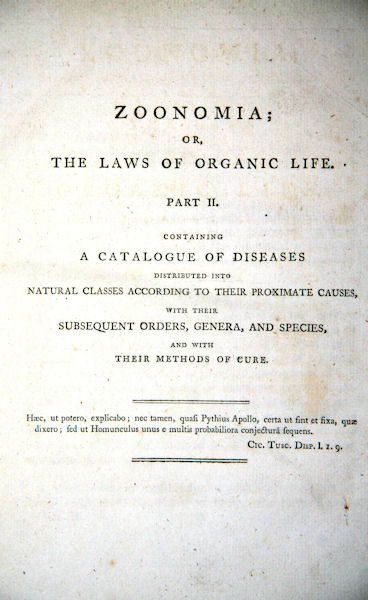

Well, as it turned out……with more science of course. And unlikely as it might seem, with quotes from the book whose spine forms the header of this very blog: Erasmus Darwin’s Zoonomia. (Erasmus was Charles Darwin’s grandfather….how many times)

Over to you, Humph….

‘There is a law of sensation which may be called the law of continuity & contrast of which you may read in Darwin’s Zoonomia [sic]. An example is – look long on a spot of pink, & close your eyes, the impression will continue for some time & will then be succeeded by a green light. For some days after I quitted you I had the pink light in my eyes & the rosy feelings in my heart, but now the green hue & feelings – not of jealousy – but of regret are come.’

Smooth, or what?

I’m not the first to spot Davy’s creative application of ground-breaking ideas in colour perception; the above passage is from Richard Holmes’s award-winning Age of Wonder. But what’s it all about? Let’s start with Zoonomia.

Erasmus describes his experiments on colour and the eye in Volume I, Section III: Motions of the Retina; and Section XI: Ocular Spectra.

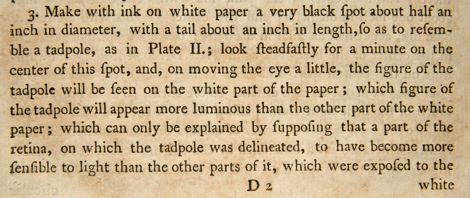

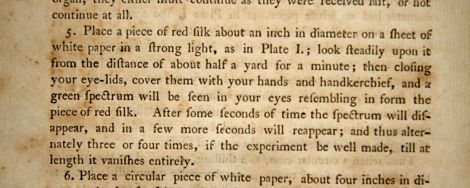

In his letter to Jane Apreece, Davy is referring to this experiment (Warning for the unfamiliar: f = s):

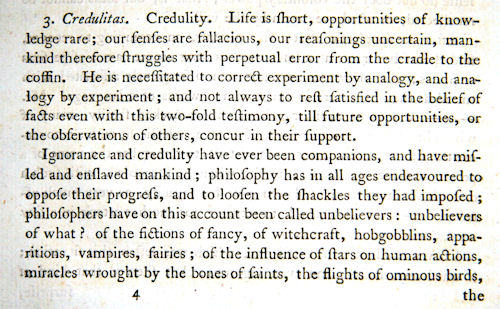

Later, Erasmus restates the experiment and proposes a mechanism for the observed effect:

Darwin’s experiments covered a range of colour and contrast effects. Here in his ‘tadpole’ experiment he interprets the bright after-image we see after staring at a dark object, explained again in terms of conditioning and sensitivity of the retina.

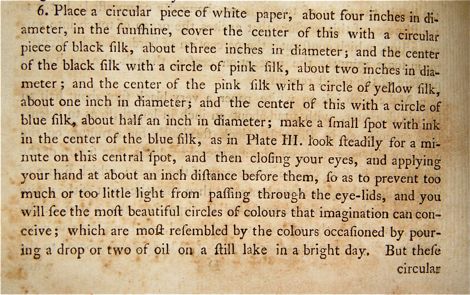

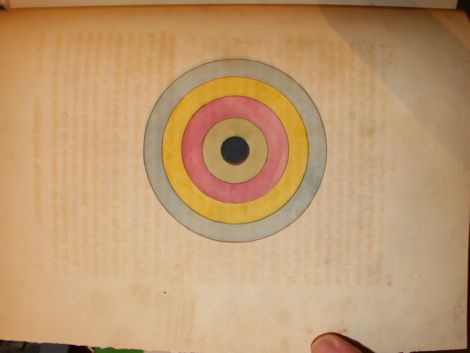

The drawings in Zoonomia are individually hand drawn and hand coloured. In this passage, Erasmus encourages his readers to partake of some drawing-room diversion using silks of many colours:

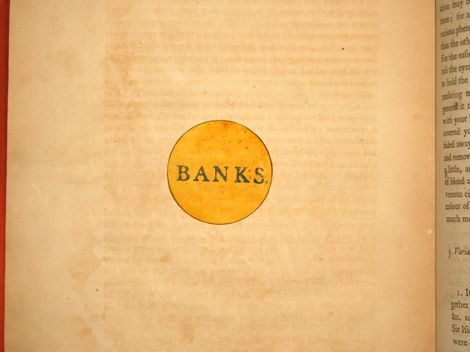

All exciting stuff, not least for Erasmus, who betrays his giddiness in this chuckling wind up to his analysis, where he curries favour with the incumbent president of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks.

“I was surprised, and agreeably amused, with the following experiment. I covered a paper about four inches square with yellow, and with a pen filled with a blue colour wrote upon the middle of it the word BANKS in capitals, and sitting with my back to the sun, fixed my eyes for a minute exactly on the centre of the letter N in the middle of the word;after closing my eyes, and shading them somewhat with my hand, the word was dinstinctly seen in the spectrum in yellow letters on a blue field; and then, on opening my eyes on a yellowish wall at twenty feet distance, the magnified name of BANKS appeared written on the wall in golden characters.” [Banks was elected President of the Royal Society in 1778].

Did Erasmus get it right with all that stuff about flexing of the antagonist fibres and analogy to the muscles? Well, he wasn’t a million miles away from the truth. Indeed, it looks like yet another case of Erasmus Darwin not getting the credit he deserves for being ahead of the game.

Here’s a modern popular version of the tadpole ‘trick’ (Credit: from here)

The idea is you stare at the bulb for 20 or 30 seconds then look at the white space to the right of it. The popular description of the effect is in terms of the retina cells stimulated by the light portions of the image being desensitized more than those which respond to the dark part of the image – so that the least depleted cells react more strongly when the eye switches to the more uniform all-white image next to the bulb.

The modern authors note also that the size of the afterimage varies directly with the distance of the surface on which it is viewed: a manifestation of Emmert’s Law. This is consistent with Erasmus’s report of the name BANKS writ large on his garden wall.

Likewise, the modern interpretation of colour afterimages is popularly framed in terms of how ‘fatigued’ cells respond to light (See how fatigued’ aligns with Erasmus’s muscular references). Erasmus didn’t know we have two types of light-sensitive cells in the eye: cones (that broadly speaking detect colour) and rods (that are more sensitive to absolute brightness), and that the cones themselves are sub-divided to be maximally sensitive to red , blue and green (RGB).

But he did understand the concept of complementary colours, and recognised that whatever part of the retina detects the colour red becomes fatigued through over-exposure; he’d got the principle that green appears againt white as a kind of negative red ).

If we dig a little deeper we find the brain-proper conspires with the retina to consider what we see in terms of black-white, red-green, and blue-yellow opponencies. And the corresponding three sets of retinal cells operate in a pretty arithmetical fashion: the electrical impulse sent to the brain by the red-green cells is proportional to the net red-green exposure to light that the cell has experienced in recent time; likewise the blue-yellow sensitive cells.

That’s all clear then.

What bugs me a wee bit is that in my research for this post I never once saw a reference to Erasmus Darwin. Rather, the standard historical reference seems to be the German psychologist Ewald Hering (1834-1919), who is credited with the first observations of the phenomenon.

Hold the horses – it’s Valentines Day

Ok, we got a bit lost in the science there. And I got a bit hot under the collar; eh-hem. So, the real question is: did Davy’s colourful overtures hit the mark? Well, sort of. Humphry Davy and Jane Apreece married the following year in 1812. The bad news is it didn’t really work out longterm.

All the same, Davy shone ever bright in his science. Already famous for discovering a whole range of new chemical elements, including via separation by electrolysis potassium and sodium, and chlorine gas; he went on to discover elemental iodine and, for good measure, invented the Davy Lamp – thereby saving who knows how many thousands of lives in the mining indistry. In 1820, when Banks’s death ended his 40+ year run at the head of the Royal Society, Davy was elected President.

All of which doubtless kept a bit of colour in his cheeks.

Sources

Darwin, Erasmus. Zoonomia Vol 1 Pub. J.Johnson 1796 (photos are from author’s copy)

Holmes, Richard. Age of Wonder. Pub. Harper Press (the softback is out for about £7 now – buy it!)

And Resources

The Guttenburg version of Zoonomia Vol 1 is here.