How do different people and groups of people view science? What do they know about it? What do they think is important?

To help answer those questions – here’s a fun ‘Sci-Art’ idea with a serious side.

You see, proof that Big Science is alive and well at Imperial College, my colleagues Arko Olesk, Graham Paterson and I went crazy last month and invested in an A3 sketch pad and a felt-tip pen.

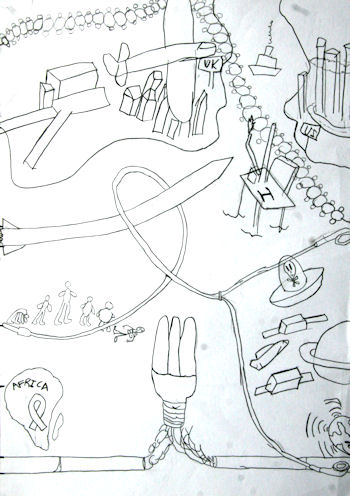

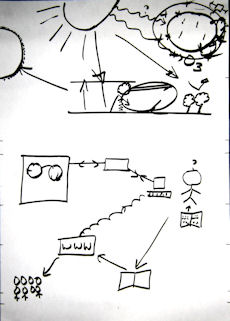

So armed, we’ve been accosting members of the public, scientists, and science communicators, and, looking over their shoulders in the nicest possible way, asking them to DRAW what they think is important about science.

We’ve made audio recordings of what was said whilst drawing and, in a bid to capture all this diversity in an intriguing and memorable way, stitched the pictures together in the manner of the surrealists’ Exquisite Corpse. A little photoshopping nicely finished this testimony to all our efforts.

Pretty, but what’s been achieved here?

Our thinking was that long questionnaires and government surveys have their place, but they don’t catch those instinctive, spur of the moment thoughts and reactions that show where someone’s really coming from. We wanted to capture the ideas that get lost in a more calculated response. OK – we gave our subjects some warning, but we saw real spontaniety too.

On to our subjects and something of the learning…… We are indebted to Imperial’s Head of Physics – Professor Joanna Haigh, Programmes Developer at the London Science Museum’s Dana Centre – Dr Maya Losa Mendiratta, and our ‘public’ – Emma Sears and Gareth (14 yrs), for being temporary artists and great sports in equal measure.

To give you a flavour of what we learned from our statistically unrepresentative ‘spot sample’, take the youngest of our ‘public’ – Gareth. Given his relatively young age, I was struck by his breadth of knowledge: we have AIDs in Africa, perils of passive smoking, space clutter, hearing damage, nuclear weapons, carbon footprint, materials shortages, and nothing less than the “de-evolution” of the human race. A follow-up study might probe for depth, but he came over as a walking endorsement of the contextual focus of UK science teaching (although for me the jury’s still out).

Scientist Joanna Haigh chose to illustrate the scientific method, to which end she referenced her specialisation in atmospheric physics, especially topical given the field’s impact on the global warming debate (which all our subjects referenced).

Some of our subjects were quite complimentary about science journalism – others less so. And we saw a ‘blurring of the lines’ between what a group or public really is. Some of our scientists also dealt with the media, making them part communicator. When it comes to keeping up with the sciences distant from her field, Haigh reads the popular press, like New Scientist, rather than specialist journals.

Haigh was also strong on interdisciplinary working, a theme that resonated with science communicator Maya’s comments about scientists needing to avoid stereotyping in one field. Yet that idea can conflict with another view we got that it is the focused scientist who traditionally ‘gets on’. Behind all this I sensed a yearning for some enabling change in the scientific establishment.

Climate was perhaps THE common scientific theme, with Emma talking about water conservation and desalination. She also discussed affordable medicine, which resonated with Gareth’s comments on AIDS. The possibility of extra-terrestrial life (not so much UFOs – despite Gareth’s alien sketch) was another recurring theme.

Anyhow, my intent here is to share the idea, not this particular analysis. And I’ve also avoided academic discussion of communication models: deficit, PUS/PEST, hierarchical etc. – which this sort of exercise can inform.

Update 12th July 2009

You can watch the movie of this project here.

Tim,

Feeling really dense for just coming across this – interesting idea with a huge amount of mileage I suspect! Looking forward in anticipation to seeing where it goes.

Just one question though – how do you break through the inhibition to expression through drawing you will find in many adults, who don’t believe they can draw?

To be quite honest, the personal touch is everything! Important to contact in person, or by phone – then emphasise it’s about sketching, not high art.

As you can see and hear, our subjects did a smashing job.

Interestingly, we also contacted several high profile science communicators to draw for us – all of whom you will know, but will remain nameless! – and it was definitely a mixed bag of response (although they did all respond).