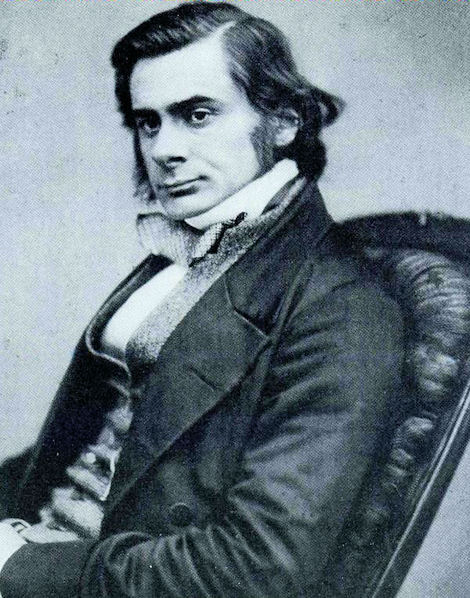

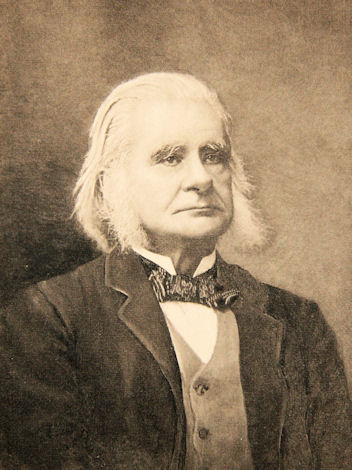

I can’t let the day go by without some sort of homage to Thomas Henry Huxley (1825-1895); for today – 4th May – is indeed his birthday.

Everyone with a special interest in science, or those working in the sciences, has heard of T.H. Huxley. But for many others the name Huxley is more often associated with T.H.’s grandson Aldous – of ‘Brave New World’ fame or, closer to 20th century science and politics, Aldous’s biologist brother and founder of UNESCO Julian Huxley.

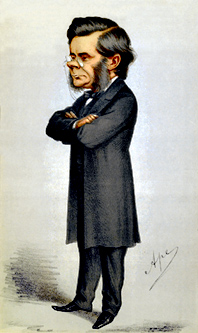

And in Darwin’s 200th anniversary year we’ve seen ‘T.H.’ come to the fore as Darwin’s Bulldog – portrayed as a kind of willing intellectual ‘heavy’, clearing the way of dissenters for Charles’s evolutionary thesis to hold forth – sending bishops flying as he went. I referenced the most recent re-enactment of Huxley’s encounter with Bishop Wilberforce during this year’s Secularist of the Year Awards here.

But Thomas Henry was very much his own man (no sexism intended). Originally trained in medicine, he served as a ship’s surgeon aboard the Rattlesnake in early life but, lacking the financial independence enjoyed by Darwin and other ‘gentlemen scientists’ of the day, had to establish his scientific credibility by hard clawing through the establishment.

In fact, T.H. should be the patron saint of impoverished scientists, for while his later life was comfortable, financial recompense during most of his career was totally out of kilter with his societal contribution and achievement. Fortunately, on an occasion when Huxley’s body failed to keep pace with his spirit, friends who were also members of the scientific ‘X-Club’ chipped in with Darwin to pay for a recuperative continental break.

Huxley’s interest was science in all its manifestations, and his legacy is today’s acceptance of science as a profession, and a system for science education that has its roots in the biology classes he held at South Kensington.

But T.H. was not happy doing just science. In fact there was a conscious moment when he was overtaken by the conviction that helping others understand science was even more important than the science itself; I guess that makes him the patron saint of science communicators as well then!

There was nothing snobbish or ‘look down your nose’ about Huxley’s lectures for working men. His monologue on ‘A Piece of Chalk’ is an icon of communication – of any sort – and can be compared with Michael Faraday’s famed public dissection of ‘The Chemical History of A Candle’ at the Royal Institution.

Being so close to nature, evolutionary concepts, and Charles Darwin, Huxley was bound to take a stance on religion. He coined the term ‘agnostic’ and declared himself as such. I think to understand exactly what HE meant by that you need to read his letters and essays. A pragmatist, Huxley did not subscribe to religious dogma through scripture, but at the same time was concerned that society could not function without something to fill the gap that would be left by, say, the removal of bibles from schools. I’ll resist several more paragraphs comparing Huxley to Richard Dawkins in this regard; suffice to say I believe there are fundamental similarities between the two – but also differences.

Although you’d never guess from the title or intro to this blog, it was Huxley, and specifically Adrian Desmond’s biographies – ‘The Devil’s Desciple’ and ‘From Devil’s Desciple to Evolution’s High Priest’ (which respectively deal with Huxley’s earlier and later years) that have most inspired me – in quite fundamental ways.

Anyone who ‘Twitters’ knows there are an awful lot of motivational gurus out there and, while I’m not against that, believe you’ll find in Huxley’s life a 90% exemplar of the right-thinking, right-stuff behaviour for a happy life. In fact, exploring the Zoonomian Archives I find I referenced the great man in August last year, here comparing his philosophy with that of a former headmaster at my school; perhaps the Huxley influence runs deeper than I know? There endeth that lesson.

If you want to know more about T.H., read the Desmond biographies alongside some of Huxley’s collected essays. And for a deeper understanding, the ‘Life and Letters of T.H.Huxley’ – published by his son Leonard in 1901 are engaging. The Huxley File is a comprehensive web reference.

Now something for the Huxley aficionados and the just plain interested:

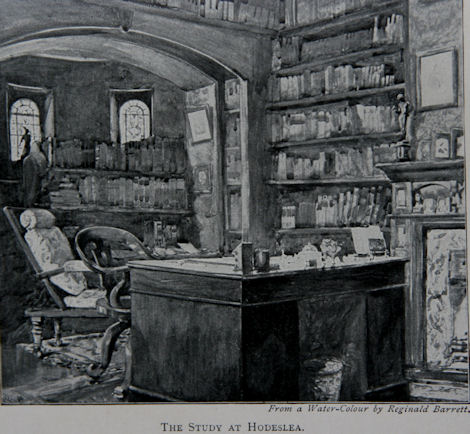

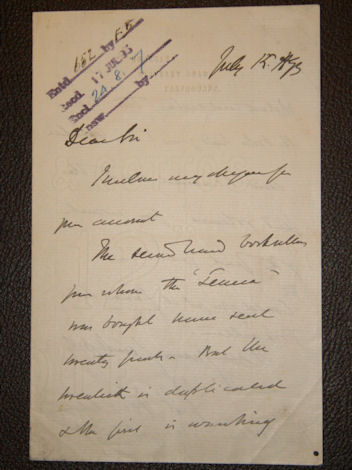

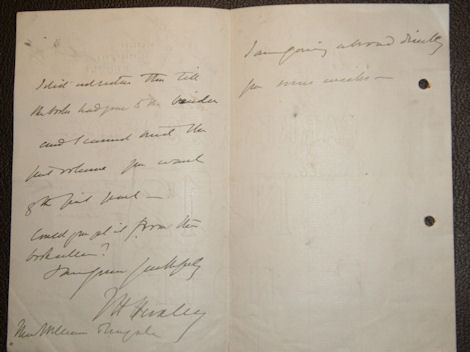

On 15th July 1893, Huxley was sitting at his desk in his home Hodeslea, in Eastborne in the south of England, writing a letter to Sir J Skelton; you can find it on p.383 of the U.S. Appleton edition of ‘Letters’.

Huxley tells Skelton how he never fully recovered from a bout of influenza in the spring and is setting off the next day to Maloja (Switzerland) for one of his recuperative breaks. As Huxley says: “It mended up the shaky old heart-pump five years ago, and I hope will again.” The next recorded letter I can find is from October 1st 1893. But Huxley did write at least one more letter on the 15th July – I know because I have it :-).

The note is to the publishers Williams and Norgate, sending a cheque as payment on his account, and asking them to obtain a missing volume.

So, it’s not exactly a keystone in the scientific chronology. But, taken in the context of the Skelton letter, Huxley’s last line does conjour up images of packed suitcases and trunks: ‘I am going abroad directly for nine weeks‘. Proving……I’m just a big romantic at heart.

Of related interest….

Liz Maloney explores Huxley’s time in Eastbourne, and puts a few wrong perceptions right in the process. Thomas Henry Huxley: A Good Eastbourne Neighbour, in the Eastbourne Local Historian.

Thanks for your delightful piece on Huxley. I have been a fan of his for several years and was looking for someone else who is celebrating his birthday today. I also appreciate the other references you provide. I have read Adrian Desmond’s biography, which, alas, I had to buy online as it was out of print. I understand it is back in print now.

While Darwin was certainly the hero of the era, and our era as well, Huxley – and Chauncey Wright – deserve our attention and gratitude for their remarkable contributions as well.

Again, thanks for the article and pictures.

Glad you enjoyed the piece Jon. And thanks for highlighting Chauncey Wright as another unsung voice on evolution and the philosophy of science.

Nice scoop! And very interesting post too. I love these little details of where these great men lived. Quite a place, wasn’t it?

Hodeslea was my childhood home and I count myself very fortunate to have lived in the ‘cottage’ of such a great thinker. It is a wonderful place, full of warmth and beauty. I particularly loved sitting in Thomas Henry’s study, which still has the beautiful stained-glass windows that you can see in the illustration above. I thoroughly enjoy reading articles on TH, so thank you Tim!

Nicola, great to hear from you.

Goodness – what a thing – living in Thomas Huxley’s home. How inspiring!

I believe Huxley designed the house himself, so it will be a true reflection of his character.

Strangely, I’ve never visited – even the outside. Must put that right one day soon.

Regards, Tim

Visiting the grave of Aldous I found out that both his father and his mother were born on 11 December. I was saddened to learn that both ‘Laleham’ and the house where Brave New World was written are no longer there.

Ries, thanks for that. It is sad when these houses disappear, taking their associations with them.

I’ve just had a look at my copy of ‘The Huxleys’ by Ronald Clark, where it says Aldous returned from the USA to visit the house when he was ill, near the end of his life. He died in 1963, so it must have been demolished relatively recently. I guess the full significance of the Huxley’s as a family was not really recognised even then.