It’s many years since that winter weekend I met up with friends in the UK’s Lake District National Park, intent on hiking the slopes of Helvellyn.

Helvellyn (Photo: Simon Ledingham, WikiCommons)

We’d arrived in groups from various locations, and it was during the traditional kitting-up ritual, managed out the back of our respective vehicles, that the full realisation of my ill-preparedness struck home.

Confidence in my sturdy boots and fleece failed to counter the sinking dread I felt as my friends systematically bedecked themselves, NASA pre-flight-ops style, with all the latest snow gear. The thing was, I simply didn’t own, or had neglected to bring, the mittens, over-trousers, goggles, and miscellaneous species of crampons and ice-axe recommended by the now darkening sky.

Just as well I was in the safe invincibility of my early twenties.

So off up the hill went we. Almost immediately it started snowing – gently at first, with a serious deterioration setting in at 2000 feet; a full-blown blizzard now: horizontal snow, near zero-visibility, heavy reliance on compass etc.

I stood clown-like, my gaiterless cotton trousers stiff as boards, the ice caking and cracking as I lifted my legs through the thick snow. My fingers and face went numb. Resplendent in Gortex, my fellow hikers peered out from their hermetic cocoons, reflectorised goggles glinting from deep within wind-cheating hoods. Proffered spare socks were gratefully accepted and fashioned into makeshift gloves.

Then as the storm blew into near total white-out, we made the only possible decision, irrespective of equipment, and turned around.

Had we pushed on, things could have got nasty. As it was, we’d still managed something of a walk, and I guess I got what I deserved by way of a sound freezing and lesson learned. You’ve got the picture.

In Good Company

This mildy embarrassing tale comes to mind because of research I’ve been doing into the history of botany (and science stuff in general) in Wales.

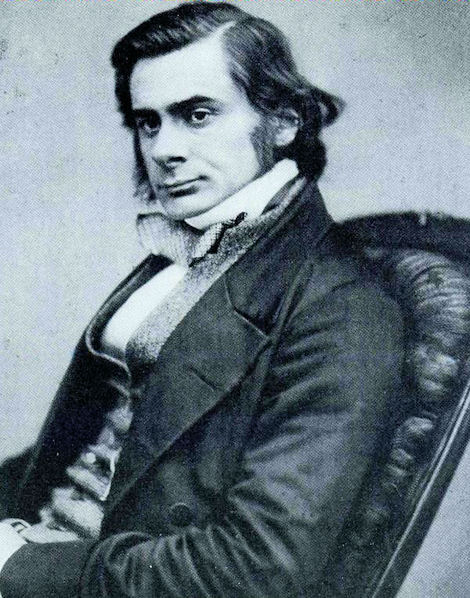

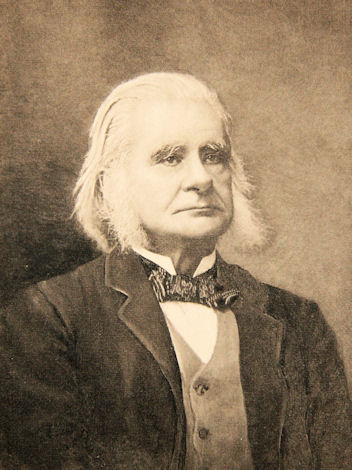

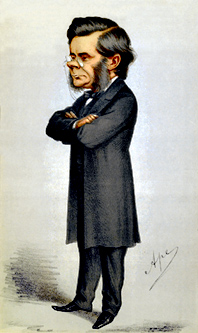

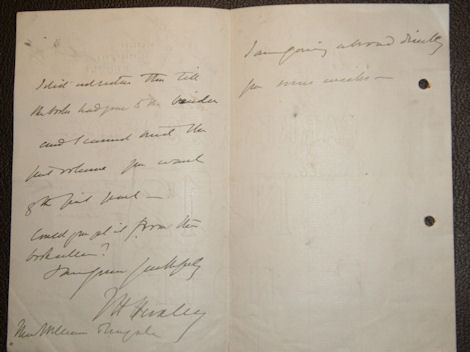

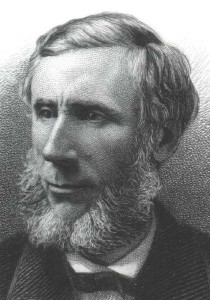

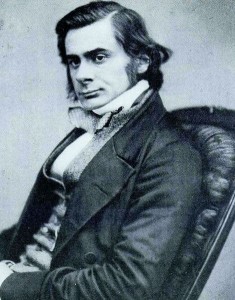

And as it turns out, I’m not the first to show up for a mountain ascent without the proper kit. What’s surprising perhaps is that, among scientists of the Victorian age, that honour goes to none other than seasoned Alpinist John Tyndall and ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ Thomas Huxley for their 1860 ascent of – not Helvellyn this time – but Mount Snowdon in North Wales.

Snowdonia was a major stomping ground for botanists in the 18th and 19th centuries, and by the 19th century, professional guiding had become quite a local industry.

In ‘The Botanists and Guides of Snowdonia’, Dewi Jones describes how mountain guide Robin Hughes first met up with Tyndall and Huxley:

“Robin Hughes was 61 when he guided John Tyndall, the famous alpine mountaineer and scientist, up Snowdon from Gorffwysfa (now Pen y Pass) in 1860. Tyndall, despite his Alpine experience, had arrived in the area on a snowy December day rather ill prepared for a winter assault on Snowdon, but they managed to gain the summit despite having to wade through drifts of soft snow. Tyndall, with his friend Huxley, had brought no ice axes or gaiters with them. They bought two rake handles at a shop in Bethesda, while on their way from Bangor to Capel Curig, and had the local blacksmith fit them with rings and iron spikes. During the ascent Tyndall complained of numbness in the feet as the result of his boots becoming filled with snow due to the absence of gaiters.“

So, with all due credit for the last minute improvisations, one still wonders what they were thinking – especially Tyndall. With Tyndall aged 40 and Huxley 35 in 1860, it’s not like either man could claim the inexperience of youth.

A bit more digging suggests Huxley at least was distracted. The Snowdon trip had been arranged by his wife Nettie, with the help of Tyndall, to relieve the depression he suffered at the recent death of their son, Noel. That Nettie had soon after given birth to another son only added to Huxley’s confusion (Desmond):

[Hal hardly knew whether] ‘it was pleasure or pain. The ground has gone from under my feet once & I hardly know how to rest on anything again’

Desmond continues:

Nettie…..conspired with Tyndall to get Hal away. That meant one thing. In unprecedented Boxing Day frosts, when the thermometer plummeted to -17 degrees, Busk and Tyndall marched him off to the rareified air of the Welsh mountains, reaching Snowdon on 28th December. The grandeur of it matched ‘most things Alpine‘. (Busk is George Busk (TJ)).

On 19th December, Huxley had written to his friend Joseph Hooker that he was:

“…going to do one sensible thing, however, viz. to rush down to Llanberis with Busk between Christmas Day and New Year’s Day and get my lungs full of hill-air for the coming session.” (The Huxley Letters.)

Llanberis is the village at the base of Snowdon, and Pen y Pass the highest point in the nearby pass. There’s a pub there now, and in 1860 an inn, where, according to Tyndall, Hughes fueled up with whisky before the trip, [and Huxley doubtless topped off his brandy flask] (Tyndall).

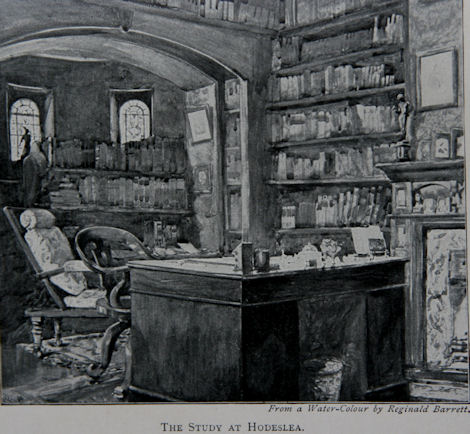

Fifteen years later, writing his book Hours of Exercise in the Alps, Tyndall’s torment on Snowdon was fresh in his mind:

“I had no gaiters, and my boots were incessantly filled with snow. My own heat sufficed for a time to melt the snow; but this clearly could not go on for ever. My left heel first became numbed and painful; and this increased till both feet were in great distress. I sought relief by quitting the track and trying to get along the impending shingle to the right. The high ridges afforded me some relief, but they were separated by couloirs in which the snow had accumulated, and through which I sometimes floundered waist-deep. The pain at length became unbearable; I sat down, took off my boots and emptied them; put them on again; tied Huxley’s pocket handkerchief round one ankle; and my own round the other, and went forward once more. It was a great improvement – the pain vanished and did not return.”

And that’s pretty much the story. Maybe it’s because I know the territory so well, or just that I’m a big fan of both these guys; but I love the imagery of Huxley and Tyndall spilling out of Pen y Pass with their half-cut guide, then trogging up Snowdon with their frozen feet and rake handles.

Anyway, all this staring at a computer screen is unhealthy; I’m off out.

Now where did I put those gloves……

Sources

Jones, Dewi. The Botanists and Guides of Snowdonia. Pub. Gwasg Carreg Gwalch (Jun 1996), ISBN-10: 0863813836, ISBN-13: 978-0863813832

Tyndall, J. Hours of Exercise in the Alps. Pub. Appleton and Company 1875 (Tyndall originally described his exploits in the Saturday Review 6 Jan 1861 as ‘The Ascent of Snowdon in Winter‘, but clearly felt the tale was worth re-telling in his Alpine book)

Desmond, Adrian. Huxley The Devil’s Disciple. Pub. MIchael Joseph 1994. pp 289-290.

Jones, G.Lindsay. The Capel Curig Footpaths up Snowdon, A Brief History (link to pdf at http://www.snowdonia-society.org.uk)

The Huxley File (Charles Blinderman) at Clark University http://aleph0.clarku.edu/huxley/

Clark, R.W. The Huxleys. Pub. Heinemann, 1968. P64

Related posts on Zoonomian