A good few Zoonomian posts are based on things or events I just happen to stumble onto. And that’s certainly the case with these oak galls I snapped on a trail walk this week.

These hard woody growths, about 1.5 inches across, are induced by insects interfering with the oak plant’s bio-chemistry.

Typically a wasp, like Neuroterus albipes in the photo, lays an egg on an oak twig, along with chemicals that react with the plant’s hormones to trigger growth of the gall, making both a home and ready meal for the wasp grub. On occasion, secondary parasites of other species may join the ‘host’ grub after the gall has formed. It looks from the multiple holes like that’s what’s happened here.

Historically, oak galls have been useful to humans as a main ingredient of Iron Gall Ink, in common use from before the middle ages to Victorian times. I made iron gall ink as a kid, which probably explains why I got so excited when I saw these. And while I’ll concede the skill is probably not a 21st century essential, making the stuff is quite satisfying.

So if you’re up for a little kitchen science, you will need: a handful of oak galls, some ferrous sulphate and, optionally if you want the ink to have a good consistency, some Gum Arabic.

The chemistry begins when the crushed galls are mixed with water, causing the tannin, or gallo-tannic acid COOH.C6H2(OH)2O.COC6H2(OH)3 in them to form gallic acid C6(COOH)H(OH)3H. Adding hydrated ferrous sulphate FeSO4, 7 H2O to this forms the ink, a soluble ferrous tannate complex.

As regards procedure, you should get a workable product by smashing up 5 or 6 oak galls and boiling them down to about a 1/4 pint in water and filtering the liquid through a cloth or handkerchief; then dissolve about a teaspoon of ferrous sulphate in a shot-glass sized measure, and mix the two together. Instant medieval ink. For a much more thorough and professional approach, see this article from the Conservation Division of the Library of Congress. BTW – ferrous sulphate can be bought in art shops, garden supply stores, and some health stores – you want iron(II)sulphate, FeSO4 – not anything else.

The advantage iron gall ink brought over previous inks was its permanence. Because ferrous tannate is water soluble, the ink soaks into the paper, where the ferrous tannate oxidises to insoluble – and darker – ferric tannate, which is now trapped in the fabric of the paper. Various refinements are seen in recipes, such as the addition of extra acid, maybe as vinegar, to keep the ink from oxidising in the pot, as it were. A drawback of iron gall inks is their corrosive action, sometimes only apparent over a long period, and in extreme cases resulting in writing literally dropping out of the paper.

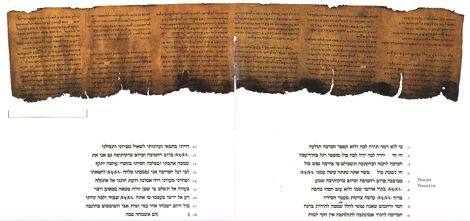

Despite the corrosion issues, many famous documents were written in iron gall ink, including the dead sea scrolls (the black ink that is; the red ink is cinnabar, or mercuric sulphide HgS), and the Constitution of the United States.