I haven’t yet read James Gleick’s latest book Information, but was glad of the chance to hear him in conversation with Nico MacDonald at London’s RSA yesterday for a flavour of what’s in store. This is a brief write-up of my notes and some observations – it’s not a book review! (That may come later…)

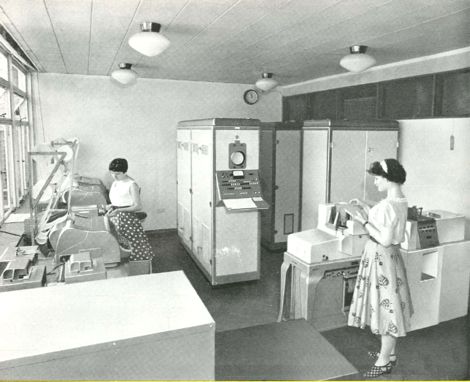

The broad discussion covered topics ranging from the history of Information Theory, how new communications systems and technologies come about and how they’re applied, the rapid pace of developments, and related issues around information quality, choice, control, value, and authority.

Information Theory

Gleick introduced the father of Information Theory, Claude Shannon, who, building on foundations set down by George Boole and Alan Turing, developed the first mathematical theory of communication and the idea that information is measureable – in ‘bits’.

His approach of separating information from meaning in a structured scientific way was another first, launching a way of thinking that has since fed into all areas of formal communications and training.

Shannon’s ideas evolved out of work addressing real-world communications engineering problems at his employer Bell Laboratories, while other developments in information theory were driven by military objectives like those related to the codebreakers at Bletchley Park and the communication needs of the Cold War.

Development and Impact of the new

Gleick believes new technologies and systems appear first, followed by a series of highly unpredictable applications. Who, for example, would have thought the recently invented radio would play a critical role in capturing the murderer Dr. CrippenSee Note 1. Escaping to America by boat, Crippen was intercepted and arrested in Canadian waters after a wireless telegram exchange with the British Police.

But do new ideas and technologies just appear? Gleick argues that intellectual invention happens when the time is right. I’m not 100 percent clear on this, but he may have been referring to times of inspired national growth, and/or where intellectual groundwork has been done in related or previously unrelated fields, as was the case with Shannon embracing Boole’s and Turin’s legacy. And once these systems arrive, says Gleick, it’s not unusual to see “all hell breaking loose”.

Consider the geographical reach and speed at which information jets around the world today. I trust he’ll forgive me for this in the interest of illustration, but when Nico MacDonald mis-pronounced Gleick’s name during introductions today (Gleick pronounces his name ‘Glick’), that little faux pas was broadcast live, archived for webcast, and picked up by at least one troublesome blogger :-). That’s what this web-enabled, multi-media, Googlised, Twitterific world will do for you. On the other hand, those same information systems do little to inform us how we should pronounce ‘Gleick’; it’s not like every textual instance is accompanied by a phonetic brief. (I got it wrong too, so I guess we’re all better people for the experience.)

It’s also apparent that the forms of knowledge we are comfortable with are changing. Gleick recounted the story of Zick Rubin, whose recent piece in the New York Times titled “how the internet tried to kill me” describes how Rubin found his own death reported on a wiki – something of a shock to say the least. As it turned out, the wiki itself wasn’t the culprit, but a printed directory from which false information had been drawn. Had Rubin not run his search, the directory’s failings would never have come to light, and at least the wiki can, and has, been corrected at the press of a button.

Choice and control

Whether it’s the phone, radio, or world wide web, Gleick believes we’ve always driven our communications systems for more efficiency. But now the new systems and tools are coming ever thicker and faster – tempting us, thrusting themselves upon us – with Ads!

This overload is forcing us to make choices: Do I sign up to this? Who do I follow / unfollow? What’s my decision criteria? As an audience member summed up: “Our attention matters and we should think more how best to mobilise it”.

Once again, a discussion at the start of the session is topical: this time on the merits and de-merits of in-session Tweeting. As you might expect in the spirit of an Information flavoured event, the RSA had laid on WiFi and a hashtag so attendees could Tweet from the meeting. But I don’t think Gleick, while playing along gamefully, was really up for it – suggesting it might distract us from the discussion. And while I fully support in-event Tweeting, he is of course dead right; it’s a self-inflicted distraction that needs self-management. I’ve come across similar mini-controversies concerning chit-chat and questions during presentations in virtual worlds.

Value, quality, filtration

Into the Q&A, and a discussion on the potential for information to add value and generate competitive advantage. The conclusion here is that Gleick sees value linked to overcoming new economic challenges, so: publishers exploring new business models for e-books, and newspapers “scared to death about Twitter” looking for ways to compete with free news.

And as to us being overwhelmed by the sheer volume of information – reliable and unreliable – that all these new systems are generating? Gleick thinks not, but only if we sort out faster methods of recovering quality information and making intelligent recommendations. Efficient suppliers of those sorts of services will find themselves in a growth business.

Authority

If the information is good and there’s one set of agreed facts, then conclusions will speak for themselves – right? Wrong, says Gleick, pointing to those who would resist the overwhelming evidence for climate change; and that small group of Americans who still dispute Obama was born on Hawaii.

Moreover, he worries we might lose science as an “authoritative, trustworthy, account” in a world – as MacDonald observed – where some people decide a position upfront, only then looking to science to back it up – the antithesis of the scientific attitude of finding out facts and seeing where they lead.

Age of the information zombies

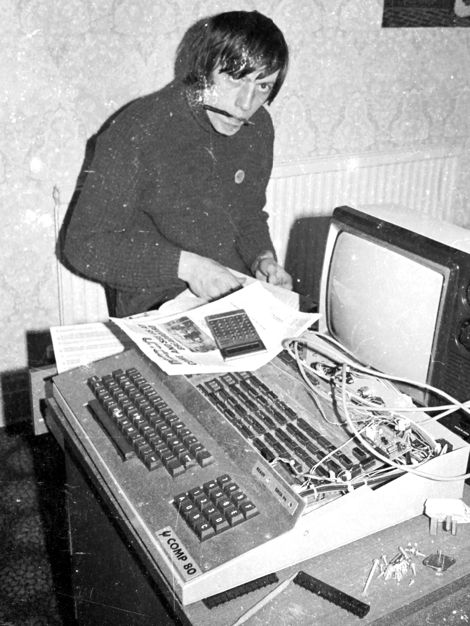

O.k., no one even mentioned information zombies. But the audience did wonder if access to ‘too much, too easy’ information might stop us (and particularly students) from concentrating and analysing properly. I got the impression Gleick was sanguine on this, but with a note of caution given we don’t even know the full effect that replacing mental arithematic with calculators has had, never mind the impact of the full on info-fest that is Google.

O.k., no one even mentioned information zombies. But the audience did wonder if access to ‘too much, too easy’ information might stop us (and particularly students) from concentrating and analysing properly. I got the impression Gleick was sanguine on this, but with a note of caution given we don’t even know the full effect that replacing mental arithematic with calculators has had, never mind the impact of the full on info-fest that is Google.

So, that was pretty much it – a thoroughly enjoyable lunchtime.

And as you see, I’ve got my signed copy of Information. Hopefully some ‘bits’ will agree with what I’ve just written :-P.

Note 1 – Updated 14/4/11. There was a mix up over stories in the conversation, with Crippen being confused with the murderer John Tawell. In 1845, Tawell was captured at Paddington Station thanks to the new telegraph (wired) being used to signal ahead that he was on the train from Slough where he had committed the murder. I’ve filled in the correct later story for Crippen, which is an analagous example but for the wireless rather than wired telegraph.

Event Audio – The audio of the event is here at the RSA’s Website

Royal Society Vidcast – Gleick presented at the Royal Society on the following day. Here is the vidcast at the RS’s website.

Also of interest: James Gleick interviewed on CastRoller