I’d heard of Alain de Botton’s School of Life and its “good ideas for everyday living“; I just hadn’t been to one of their ‘Sunday Sermons’.

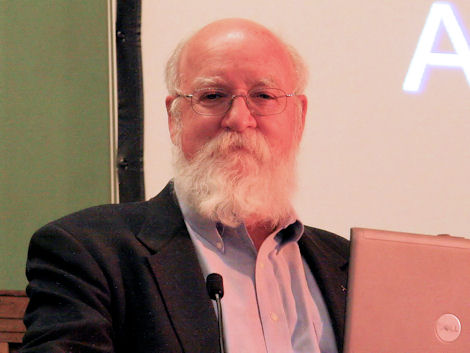

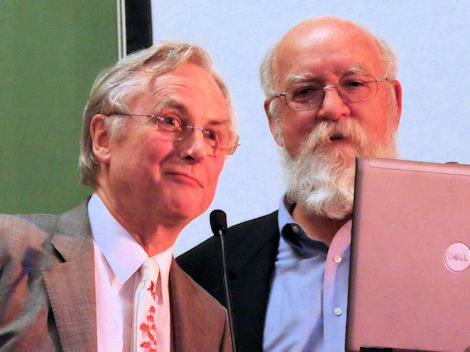

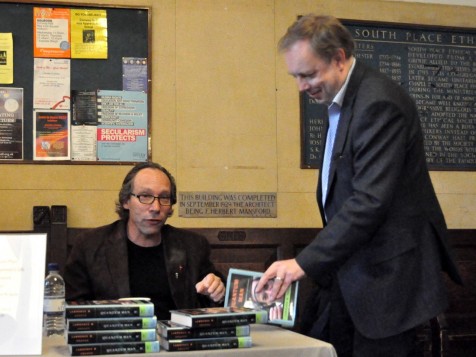

So arriving at Conway Hall yesterday to hear theoretical physicist and all-round science communicator Professor Lawrence Krauss talk about Cosmic Connections, it was an unexpected but not disagreeable surprise to find David Bowie and a seven foot spandex-clad devil stirred into the mix. I for one can’t think of a better preparation for contemplating one’s insignificance in a miserable futureless universe than a good singalong to Space Oddity.

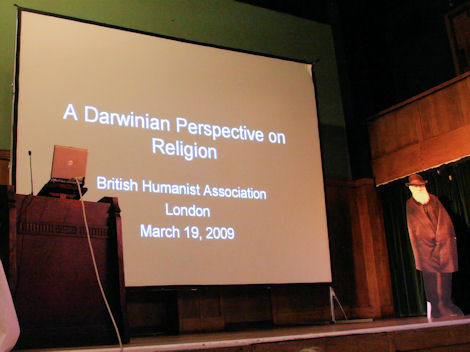

On the face of it, Krauss’s ultimate message is a bit grim: that our expanding, accelerating, universe will eventually dilate into cold, empty, blackness. But, more positively, he’s saying we should take all that as read and concentrate on our perspective: understand what we really are and how we connect with the universe. Then the journey to oblivion doesn’t look so miserable afterall; it looks fascinating – even poetic.

Krauss’s consciousness-raising / cheer-up therapy centred around three less than obvious connections we have with the cosmos:

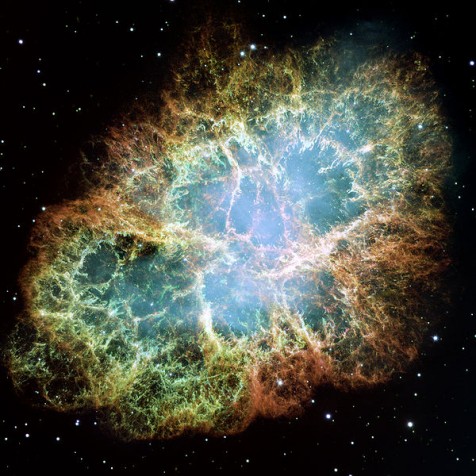

First off – we are the universe. We’re made of stars. The heavy elements that make us up could only have been made in stars, and they could only end up as part of us if they were blasted out of exploding stars: the supernovae.

Call me a romantic, but I like the imagery. Bits of me: hands and feet, arms, legs, head, brain – they didn’t just pop up a few decades ago, but have been flying around for billions of years and will be around for billions more. I’ve been inside an exploding supernova – several most likely.

Next came the connectedness of life, with a nice story of Krauss sitting to write a physics paper, aware he’s breathing the very atoms breathed by Einstein as he formulated his own theories (inspired inhalation?). We’ve all got a bit of Julius Caesar in us it seems – literally. And on the larger scale of the solar system, the exchange of possible life-bearing rocks between the Earth and other planets, including Mars, could mean we’re all extra-terrestrials without even knowing it.

Krauss’s final illustration challenges our perception that aspects of reality we normally consider outlandish and irrelevant to our day-to-day life do indeed have a direct influence on us. The mundane activity in question is navigation by Global Positioning System (GPS), where the consquences of not correcting for satellite speed (Special Relativity), and height above the Earth (gravity effect/General Relativity), on measurement of the requisite nano-second scale signal transit times, would in only a day be sufficient to put ground track navigation out by several kilometres.

I really like this GPS example and the way Krauss presented it. There was no such thing as GPS when I was at school, so all we got were stories of atomic clocks losing time when they were shot round the world on fast planes, or hypothetical astronauts of the future going on fictional journeys. To be able to relate relativistic effects to a very real navigational error that normal folk can recognise and care about is brilliant.

Who’d have thought Sunday sermons could be such fun?

Photographs copyright Tim Jones.

Final photo: Thanks Sven Klinge.

Update 4th Dec. 2011 Video of the event:

Lawrence Krauss on Cosmic Connections from The School of Life on Vimeo.

Also of interest? – Lawrence Krauss recently on Materials World with Quentin Cooper (about 15 mins in)