Grandson Charles and Grandfather Erasmus Darwin had at least one thing in common besides their illustrious name: they both took delight in figuring out how the world works – which isn’t to say they always followed the same interests.

Charles, we know, focused on the natural world – often in great, great, detail. Erasmus, less fixated but still very much the naturalist, engaged also with just about every aspect of science, technology and the trials and tribulations of the human condition you can imagine.

As happy in the botanical garden as the coachmaker’s yard or canal digger’s trench – it was all the same to him, many are the fields where Erasmus Darwin’s substantive contributions, too often unsung, resonate to the present day.

And while Charles was doubtless adventurous in mind and deed – he did afterall make the voyage of the Beagle – Erasmus, in the broader sense I would argue, ‘got out more’.

No surprise then, one evening in 1756, to find a 24 years young Erasmus Darwin at the epicentre of London society and entertainment: the pleasure gardens at Vauxhall. Less surprising still to find him back at his Nottingham lodgings pre-occupied with reverse-engineering the Gardens’ then prize crowd-pulling spectacle: the artificial waterfall, or Cascade – more of which later.

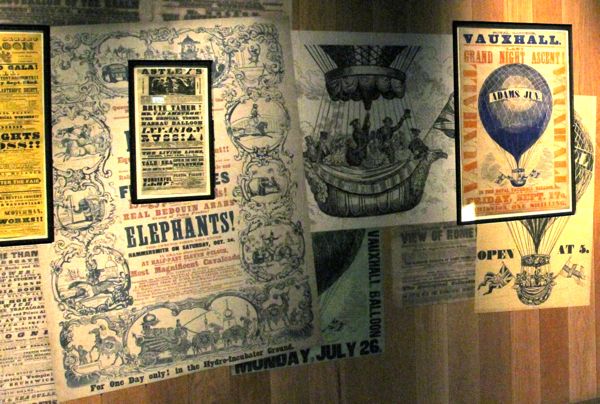

The twelve acre Vauxhall Gardens operated from 1661 to 1859, and enjoyed a fantastically diverse clientele. Anyone who was anyone – or aspired to be – had to show their face: from Kings and Queens to honest tradesmen, to a dependable spattering of pick-pockets and prostitutes.

All mixed shoulder to shoulder, intent on enjoying music, dancing, or one of the many laid-on spectacles: illuminations, fireworks, circus acts, mechanical wonders, balloon rides, battle recreations and panoramas celebrating the fetes of great explorers. Top of the list for many would be a romantic diversion with a favoured beau or belle under the tree-covered walkways.

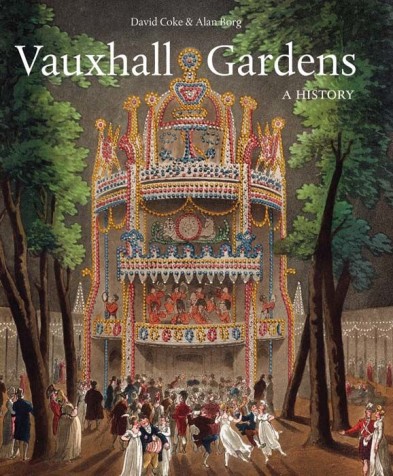

Incidentally, if you’re wondering what prompted this post – digging around in a pleasure garden – it’s down to my latest reading: a new History of Vauxhall Gardens, by David Coke and Alan Borg1: a beautifully presented, comprehensive, and accessible read. Check out the book’s website here and write-ups in the Guardian here and here

I’ve suffered from amateur social historian syndrome since arriving in London eleven years ago – it’s hard to avoid when the place drips with the stuff; but the Vauxhall interest is closer to home – literally; my old flat on the Vauxhall Bridge Road overlooked the former Gardens’ site. Now home to a plain-vanilla grassed park, the only reminder of former glories is the yearly bonfire night sputter of fireworks launched by good-natured, if boisterous, locals. (On which theme, check out this earlier post).

Reading the new history though, I was intrigued by how few famous scientists (natural philosophers in their day) or technical folk are associated with the Gardens, either as self-reporting visitors or through third-party narratives .

Maybe the great and the good of the scientific establishment eschewed egalitarian Vauxhall in favour of the more exclusive (and expensive) Ranelagh Gardens across the river in Chelsea? At least there was a stone bust of Isaac Newton on permanent display at Vauxhall.

Anyhow, it’s entirely possible a trawl through the personal letters of individuals, where they’re catalogued, would turn up further references.

For my part, I checked out Erasmus’s letters – and he didn’t disappoint.

Coming back to the artificial waterfall or cascade for a moment. Installed in 1752, Coke & Borg say of it:

To add to its theatricality, the Cascade was concealed behind a curtain which was drawn back at a particular time in the evening, as night fell, to reveal a three-dimensional illuminated scene of a landscape with a precipitous waterfall; the illusion was created with sheets of tin fixed to moving belts, turned by a team of Tyer’s [the owner] lamplighters; when it was running, the noise and spectacle must have been terrific 1.

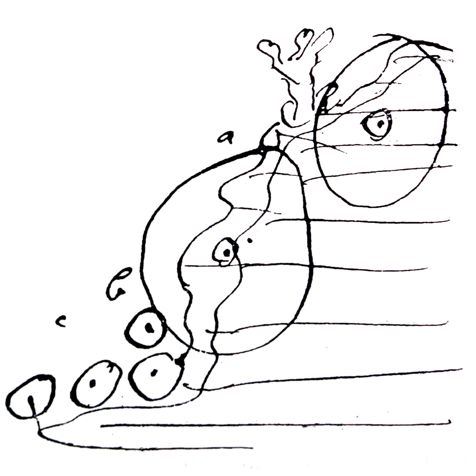

Then I found this letter from Erasmus, dated 9th Septemebr 1756, describing his interpretation of the operation of the spectacle to his friend Albert Reimarus, drawing and all:

“The artificial Water-fall at Vaux Hall I apprehend is done by pieces of Tin, loosely fix’d on the Circumferences of two Wheels. It was the Motion not being perform’d at Bottom in a parabolic Curve that first made me discover it’s not being natural. The Velocity at Top is not so great to my rememberance as at the Bottom half of the fall, as I suspect the top Wheel is less than the lower one; a Shade is put where the Wheels join. At Bottom are many less Wheels I conjecture. Now the Velocity of the fall from a to b not being encreased was another thing that shock’d my Eye. What you mean when you say “let the Water fall over a Parabola etc”, I don’t understand.“

I’m taking expressions like “The Velocity at Top is not so great to my remembrance….” as evidence Erasmus actually visited the Gardens himself in the summer of 1756, possibly accompanied by Reimarus.

For Erasmus, the waterfall ‘game’ was given away by the shape of the flow – something other than parabolic, and not moving at the expected relative speeds.

In fairness to the designer (the concept likely derived from Francis Hayman’s theatrical stagecraft), that exposing the spectacle as anything other than natural required such analysis seems high praise indeed! Incidentally, Coke & Borg maintain no visual representation of the cascade exists, so this might be as close as we get.

(As an aside, there’s also evidence Erasmus’s sister Susannah (Sukey) visited the Gardens. In a letter of 12th June 1759 to his wife Mary (Polly), Erasmus accuses his sister of exagerating the number of people attending, 30,000, saying that number would not fit3 (although audiences of 12,000 are known to have gathered). There’s also a much later association with Charles Darwin, that appears in the correspondence4; not that he visited the Gardens but, as a twelve year old boy, having watched one of Vauxhall’s favourite performers, a ventriloquist named Mr Alexandre, did imitations of animal calls – interesting eh?)

We should take care when talking about Erasmus in this period not to visualise him along the lines of the podgy, red-cheeked albeit aimiable 38 year old captured by Joseph Wright and hanging in the National Portrait Gallery. In 1756, Erasmus was 24 years old, single (he married Mary/Polly Howard the following year), and largely unknown; he’d only two months earlier unpacked his bags in Nottingham to start his first medical practice.

So this is before he moved to Lichfield, and way before the invitation to become the King’s physician, his rivalry with Samuel Johnson (of dictionary fame and a regular at Vauxhall Gardens to the degree he appears in contemporary prints), or his adulation as England’s best loved poet. Moreover, the brief spell Erasmus spent in Nottingham is sparsley covered in the literature, with no mention in the standard biographies of trips to London or the Gardens. There’s just the one letter as far as I can tell.

In conclusion, it’s nice to see Erasmus’s early credentials as both engineer and bon viveur reinforced in the one story (however much, as a fan, that assessment might be tainted by confirmation bias :-)).

In their longevity, Vauxhall Gardens represent a unique microcosm, a laboratory for the study of change in societal norms, fashion, culture, politics and contemporary opinion. Coke’s and Borg’s analysis refreshes our insight on these, and placing Erasmus Darwin at the scene adds to our understanding of his early life.

Update 4/9/11

Twitter friends have suggested Samuel Pepys as an example of a ‘scientist’ known to have visited Vauxhall. He for sure counts as one of the establishment great and the good, and was a president of the Royal Society to boot. Coke and Borg do talk about Pepys, who wrote at some length about Vauxhall Gardens in his famous diaries. I’m afraid I associate Pepys so strongly with the Gardens, and for all his other interests and achievements – not just in science, that I completely forgot to mention him – poor chap. Still, he’s one guy, and it would be interesting to see if any of the other famous scientific names of the day including Newton, Wren, or, as Rebekah Higgitt (@beckyfh) suggested via twitter, Edmund Halley or Joseph Banks made mention of Vauxhall experiences in their letters. I must say, if I had my bust up there in all its glory like Newton did, I’d be checking up on it every friday night.

Of related interest on Zoonomian: The Other Darwin Genius

References

1) Vauxhall Gardens A History, Coke, David., Borg, Alan., Yale, 2011

2) King-Hele, Desmond (Ed.), The Collected Letters of Erasmus Darwin, Cambridge, 2007, [56-6] p.35

3) King-Hele, Desmond (Ed.), The Collected Letters of Erasmus Darwin, Cambridge, 2007, [59-1] p.47

4) Darwin Correspondence Database,

http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/entry1 accessed on Thu Sep 01 2011 15:56:18 GMT+0100 (BST)

Other Sources

King-Hele, Desmond, Erasmus Darwin 1731-1802, Macmillan, 1963

King-Hele, Desmond, The Essential Writings of Erasmus Darwin, MacGibbon & Kee, 1968

King-Hele, Desmond, Erasmus Darwin A Life of Unequalled Achievement, Giles de la Mare, 1999