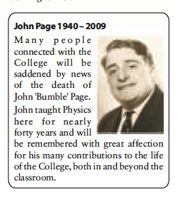

I learnt only recently, while researching the early use of computers in schools, that my physics teacher from the late seventies, John Page, had died during 2009.

Better known by his nickname ‘Bumble’ (possibly after the Dickens character), he was certainly a character himself. He was also a teacher who encouraged me to think.

For sure, Bumble covered the official syllabus: wheeling out worthy but ultimately plain vanilla physics kit like air pucks, weights, and springs. But the most interesting discussions – the ones that have stuck with me – followed some of his more off-the-wall demonstrations.

For example, as an introduction to Newton’s Laws of Motion and the Gas Laws, Bumble kicked off one lesson by discharging a black powder pistol at the front of the classroom.

The lesson started in the usual way, Bumble making his signature ponderous walk to the laboratory’s front desk, eyes looking at the floor.

Entirely normal so far, except today he carried a long-barrelled revolver in his hand, one chamber of which he proceeded to load, methodically inserting pieces of cloth, then gunpowder, then cloth again (no bullet thankfully), before compressing the package with a small ram rod. We watched in stunned silence.

Remember, this was all way before the Dunblane massacre or other school shootings, so I guess we felt a sense of intrigue rather than fear. This was Bumble anyhow – he did weird stuff. With a copper percussion cap in place, the gun was pointed in the general direction of the laboratory wall. And fired.

Within seconds of the most enormous bang echoing through the now smoke-filled laboratory, the Head of Physics, Mr Gill, closely followed by the Head of Chemistry, Mr Scottow, tumbled into the lab looking suitably alarmed. They’d clearly not been pre-briefed, and I still remember their expressions changing from shock to relief – and a glance of resignation between them – as the gunman stepped out of the smoke.

Stunts like Bumble’s Colt Navy revolver demo were attention grabbing and fun, but also an introduction to typically stretching discussions.

In this case, Bumble got us thinking about how long a gun barrel would have to be before the bullet changed direction and went back the other way. Imagine the thought processes needed for that. First off, there’s the non-intuitive realisation that a projectile in a tube can change direction if the pressure behind it falls sufficiently relative to the pressure in front of it – which theoretically can happen in a long enough gun barrel. Then there’s the skill of mentally extrapolating the familiar (relatively short barrel) to unfamiliar extremes (hugely long barrel). Thinking in abstraction and at scales beyond normal experience is useful, for scientists and non-scientists alike, in appreciating the scales relevant to fields as diverse as evolutionary biology and cosmology (and presumably also super-gun design).

Then comes the actual physics and chemistry: mechanics, thermodynamics, kinetics, friction, shock-wave propagation – not to mention the mathematical tools needed (I don’t remember if we came up with an actual quantitative answer, and suspect an analytical solution is only possible with major simplification. ) The follow-on lesson might cover ballistics: catching up with the bullet after it leaves the gun.

In a similar vein, my introduction to fluid flow through constrictions and Bernoulli’s principle took the form of the largest firework rocket I’d ever seen being launched from the school playground. In the lesson afterwards, we talked about rocket nozzle design. It turned out Bumble was licensed to make fireworks and had designed and cast his own ceramic nozzles. I still marvel that the thing came down ‘safely’ in the confines of the school yard.

So that’s how I remember Bumble. We might at times have got distracted from the strict letter of the course syllabus; but that’s the nature of real-world problems if they’re studied with sufficient rigor. And arguably as the antithesis of spoon-fed exam training, Bumble’s teaching style may not have suited all students. But personally, I love the attitude and approach to education John Page represented, and very much hope we haven’t seen the last of the Bumbles.