“A squib is a type of firework, hence damp squib: something that fails ignominiously to satisfy expectations; an anti-climax.”

Oxford English Dictionary

The opportunities for non-scientists to do science have never been greater: it’s called Citizen Science.

Helping out the professionals can involve anything from counting ladybirds in your back yard, to looking for alien life, to classifying galaxies and discovering new planets, to monitoring the population dynamics of the Rose-Ringed Parakeet. Just take your pick from the Zooniverse Smörgåsbord.

But when was the first citizen science project? I’ve been thinking about it lately, and my starter-for-ten comes from some research I did last year about fireworks. There must be other examples, so please comment if you have any.

Not to be distracted by definitions (however interesting – see Openscientist), I’m taking citizen science to mean some sort of research or project where a scientist – or what passed for one at the time – appeals to the public to report observations, measurements, or such like.

My candidate project concerns Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) Benjamin Robins, who in 1748 made a general appeal to the public to observe and report the height of rockets – ultimately with military and surveying purposes in mind – during a firework display.

Without email, podcasts, or Dara Ó Briain’s Science Club, Robins’s request appeared as an anonymous bulletin in the November 1748 issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine1 (in his excellent Fireworks: Pyrotechnic Arts and Sciences in European History2, Simon Werrett suggests Robins is the most likely author)

For if such as are curious and are from 15 to 50 miles distant from London, would carefully look out in all proper situations on the night when these fireworks are play’d off, we should then know the greatest distance to which rockets can possibly be seen; which if both the situation of the observer, and the evening be favourable, will not, I conceive, be less than 40 miles. And if ingenious gentlemen who are within 1,2 or 3 miles of the fireworks, would observe, as nicely as they can, the angle that the generality of the rockets shall make to the horizon, at their greatest height, this will determine the perpendicular ascent of those rockets to sufficient exactness.

The Gentleman’s Magazine1November 1748

Robins had made a name for himself in gunnery and ballistics, calculating for the first time how air resistance affects military projectiles3. Now he enthused over rockets for their

…very great use in geography, navigation, military affairs, and many other arts;1.

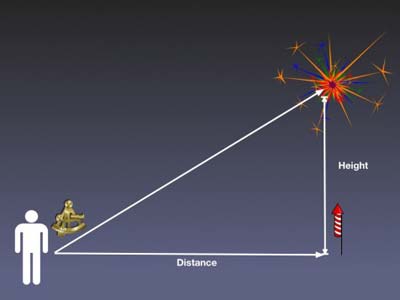

The light alone from a rocket was a useful signal in war; but Robins knew more was possible. Provided the rocket rises vertically to a known height, the observed angle between the horizon and the rocket at the top of its flight lets you calculate its distance. Before GPS and radio, this could tell you where someone was:

The map maker John Senex had already used the method for surveying4, but Robins needed more height and distance data to refine and calibrate the technique. But where would the rockets come from?

As it turned out, Robins’s timing was perfect. Bringing to an end a series of tortuous European wars, the recently signed Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle was the latest cause for national, and therefore Royal, celebration. And George II planned to celebrate in style, with a sound and light spectacular involving the launch of thousands of firework rockets. The geo-politics of the day were about to lend Robins an unlikely and unwitting hand.

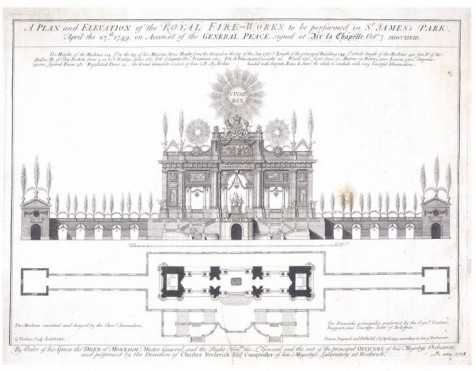

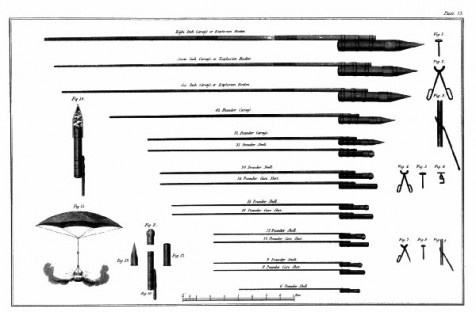

Held at Green Park, London, in April 1749, George’s display, famously accompanied by Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks, was huge. No less than 10650 rockets weighing up to 6 pounds each rose into the night sky from a 410 ft long ornate Doric temple or ‘firework machine’5 – 6000 of them reserved to go up together in the finale6.

Robins’ request for two types of data: angle measurements from those close in, and simple confirmations of visibility from those further out, came with instructions:

The observing the angle which a rocket, when highest, makes with the horizon, is not difficult. For if it be a star-light night, it is easy to mark the last position of the rocket among the stars: whence, if the time of the night be known, the altitude of the point of the heavens corresponding thereto, may be found on a celestial globe. Or if this method be thought too complex, the same thing may be done by keeping the eye at a fixed place, and then observing on the side of a distant building, some known mark, which the rocket appears to touch when highest; for the altitude of that mark may be examined next day by a quadrant; or, if a level line be carried from the place where the eye was fixed to the point perpendicularly under the mark, a triangle may be formed, whose base and perpendicular will be in the same proportion as the distance of the observer from the fireworks, is to the perpendicular ascent of the rocket.

The Gentleman’s Magazine1November 1748

Bearing in mind astronomy and triangulation are skills likely absent from most readers’ day jobs, this is quite an intimidating, albeit educational, set of instructions. So much for the procedure; how did the results pan out?

There were some issues on the night, including a large portion of the Doric temple unexpectedly catching fire during the show, and various eye witness accounts suggest the event was a little lack-lustre. But the rockets went up, and George’s spin-doctors took care of any negative PR.

The response to Robins’ experiment was more disappointing, with only one report appearing in the follow up edition of the Gentleman’s Magazine, and that from a Welshman 138 miles away near Carmarthen:

I had a clear prospect of several miles eastward where I waited with impatience till near 10 o’clock, and then saw two flashes of light, one a few minutes after the other, that rose east of me to the height of about 15 degrees above the visible horizon. I don’t pretend that I saw any body of fire, only a blaze of light, which neither descended like a meteor, nor expanded itself abroad like a lightning, but ascended and died. Clouds interrupted, that I could see no more.

Thomas Ap Cymra, Gentleman’s Magazine, May 17497

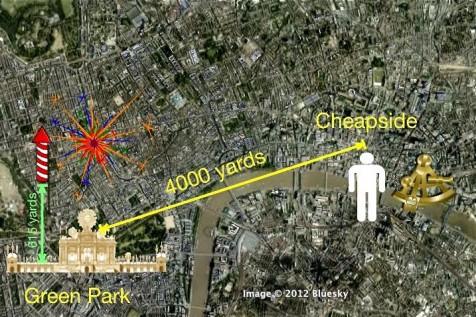

Let’s remind ourselves what 138 miles looks like:

So, how believable is Thomas Ap Cymra’s report?

At this distance, a line-of-sight view of the rocket at the top of its trajectory is out of the question, thanks to the curvature of the Earth – never mind the Brecon Beacon mountain range. But we shouldn’t write Thomas off just yet. 6000 rockets going off together would make a hell of a flash, and we know lightning from thunderstorms can be seen from many miles away. And in the First World War there were reports of flashes from the fighting in France being visible from London.

In his full letter, Thomas logically argues why his observations could not have been meteors or lightning. Off the technical topic, he then questions the suitability and cost of the event, saying how he struggles to rationalise the irony of using fireworks to celebrate a military cessation. The moaning somehow makes his observations more credible.

All the same, a single response with no elevation data must have been a disappointment to Robins. And just as well he’d taken the belt-and-braces precaution of making some of his own elevation measurements, with the help of a friend stationed 4000 yards away in Cheapside,

From these measurements, taken with a sextant with the starry background as reference, Robins was able to publish in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, that the highest Green Park rockets had risen to 8.75 degrees above the horizon, equivalent to a height of 615 yards8.

Robins made further tests after the Green Park display, trusting to friends and colleagues placed at various locations tens of miles from London – itself a non-trivial task without mobile phones – and using rockets of more consistent specification9

We have to hand it to Robins, that despite a poor public response, his was a valiant effort to stir up interest and participation using the latest communications media available to him.

We should also remember The Gentleman’s Magazine was the first publication of its type (est. 1721) and the first to reach anything like a wide audience – albeit one excluding women and the not so well-to-do. The concept of a publicly visible two-way conversation via a publication was itself recent, having first appeared in pseudo form in the fictional dialogue between characters in the Spectator Magazine (1711-12). So maybe it was just all too new.

These days, I suppose Robins might suggest participants send him a geo-mapped digital photograph of the rockets. Some would understand what they were doing – others wouldn’t – but the data would still be good. But that brings us back to asking exactly who counts as a citizen scientist, which is a whole new question, and probably a good place to stop.

References and further reading

1. ‘A Geometrical Use proposed for ‘the Fire-Works’, Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol 18 Nov. 1748, p.488.

2. Fireworks: Pyrotechnic Arts and Sciences in European History. Simon Werrett, University of Chicago Press, 2010.

3. New Principles of Gunnery, Benjamin Robins, London, J.Nourse, 1742

4. John Senex Wikipedia article

5. A description of the machine for the fireworks; with all its ornaments, and a detail of the manner in which they are to be exhibited in St.James Park, Thursday, April 27th, 1749, on account of the General Peace, signed at Aix-la-Chappelle, October 7, 1748. Published by His Majesty’s Board of Ordnance. By Gaetano Ruggieri and Gioseppe Sarti.

6. The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction. Vol 32, 1838, p.66

7. Fireworks Observed. Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol 19, May 1749, pp.217-18

8. Observations on the Height to Which Rockets Ascend; By Mr. Benjamin Robins F. R. S. Phil. Trans. 1749 46 491-496 131-133; doi:10.1098/rstl.1749.0025

9. An Account of Some Experiments, Made by Benjamin Robins Esq; F. R. S. Mr. Samuel Da Costa, and Several Other Gentlemen, in Order to Discover the Height to Which Rockets May Be Made to Ascend, and to What Distance Their Light May be Seen; by Mr. John Ellicott F. R. S. Phil. Trans. 1749 46 491-496 578-584; doi:10.1098/rstl.1749.0109