What do they say? It’s never too late and you’re never too old? I finally made it to Disneyland (Anaheim) last week.

There we were: doing all the rides – some several times, eating food that’s bad for us, buying stuff we don’t need. I so want to take the Star Tours sim home with me.

It’s a hard experience to knock. Except, looking round, aren’t the Disney icons a bit thin on the ground, especially that icon of icons – Mickey Mouse. Where’s the guy off the TV with his big mouse head, big mouse eyes and ears, flowing tailcoats? Okay, between whipping round Space Mountain and transfering the contents of the flume into my fleece, our accessibility to roaming mice is limited; but I’m still half disappointed (half thankful too) we’ve avoided a mugging by the world’s cutest rodent – me with my ‘1st Visit’ badge an’ all.

Then at the end of the day, as we sit munching Mickey surrogate pretzels, the mouse himself finally shows on the Parade float; and with that box ticked, we head home to live happily ever after.

Hurtling down LA’s great big freeway, I can only mull, through waves of incipient indigestion, the definitive paper on ‘the impact of twelve hours of corn dogs, ice cream and churros on the human body under intermittent acceleration to 3g’. Shelving that due to data-weakness in cotton candy (with a recommendation for further work), I move to the important question of why exactly is Mickey Mouse so very popular? Some thirty years ago, evolutionary biologist and sometime Disney scholar Stephen J Gould asked the very same question.

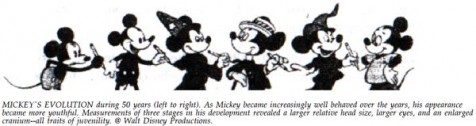

Gould’s essay, Mickey Mouse meets Konrad Lorenz, originaly pubished in the May 1979 issue of Natural History, and reappearing as ‘A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse‘ (link to pdf) in the Panda’s Thumb collection of essays, is a light-hearted yet sound scientific analysis of how Disney artists changed Mickey’s features over the years to make him more innately appealing to us. Perhaps not knowingly, but in biological terms they’d neotenized him, migrating his more adult features to the juvenile forms we see, and are programmed to endear, in human children. It’s one of my favourite pieces of science communication and a recommended read.

Animals, real or caricatured, score high on the cute scale if they have: (a) a large eye size compared to head-length, (b) a large head size to body-length, and (c) a large cranium (Gould measured a ‘cranial vault’ ratio for this, only meaningful for Mickey in profile, but equating to what Lorenz describes as “predominance of the brain capsule”). They display short, thick, extremities – like stubby legs (Disney achieved the illusion by putting Mickey in shorts), and a short snout (in cartoonland, only villains sport pointy snouts – think the weasels from Who Framed Roger Rabbit).

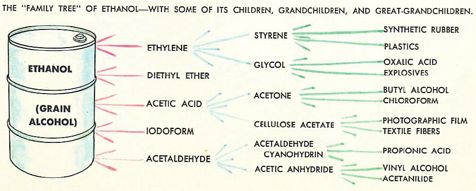

The principles from Lorenz’s and Gould’s work have been applied to everything from vehicle design to this assessment of how cute NASA’s Mars rover Spirit is,…to pretzels.

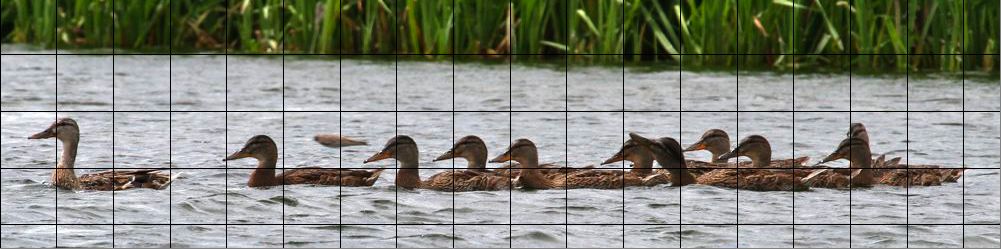

Applied to animals, they suggest our attitude, affection, concern, and the general way we treat species will be influenced by how closely each resembles a human child – how juvenile they appear. Conservationists call it ‘survival of the cutest’ – whereby public conservation support favours attractive species over more deserving cases under a greater threat of extinction. It’s the reason pandas and badgers get more sympathy than the Purple Burrowing Frog (Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis), or the Helmeted Hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) – to pull a couple of real lookers from the IUCN Red List; the former is ‘endangered’, the latter a ‘near threatened’ species.

Even favoured species like dolphins fall off the radar once a variant moves away from a norm we can easily anthropomorphise. Compare the Ganges (endangered) and Yangtze (critically endangered, possibly extinct) river dolphins with their slightly odd-looking extended beaks, with the familiar smiley Common Short-Beaked dolphin (‘Least Concern’ on the IUCN list).

I’m bringing badgers into this because of their prominence in the UK news at the moment, where the government has introduced a controversial culling policy to reduce Bovine TB, which badgers carry. Controversy centres on the effectiveness of culling (by shooting at feed lures) over other controls like vaccination, and a general point on how transparently science or politics based the decisions have been. In terms of its conservation status, the Eurasian Badger (Meles meles) is classified by the IUCN as a ‘least concern’ species.

Taking nothing away from the arguments, it’s interesting to test the badger against Gould’s cuteness criteria to see how looks might be influencing popular support. I got the idea from this Guardian piece that’s against the culling, but suggesting that with respect to “one of Britain’s best-loved animals”…”our attachment to badgers may be irrational” (as is culling, in that author’s view).

Off the blocks things don’t look so good, Mr Badger being a fully paid-up member of your actual weasel family an’ all. But he’s not stoatish, and from various photos on the web (my preferred methodology short of taking callipers to roadkill), I score him an apparent head to body ratio of five (20%), falling to four (25%) when he bunches up like they do. Not even up with Mickey’s early Steamboat Willie incarnation at 35%, but still in the ballpark.

Compared to Mickey’s eye to head ratio of 27% to 42% over his career, our badger comes in at unbecoming ratios as low as 7% (measured up the snout, nose to ear) to at best 15% (measured in profile). But look again. What we really see in a badger’s face isn’t its beady little weasel eyes, but that glorious stripe (think pandas eyes). Calculated on stripe width at the eye, the ratios triple, up to a far cuter 35% for the profile. On the stubby legs criterion the badger is home and dry; it’s hard to even make them out under the fur – a bit like Disney hiding Mickey’s spindles under baggy shorts. The snout is an enigma though, and there’s no getting round it. Does the apparent integration of snout, cranium and neck into a continuous cone soften the effect? Or maybe we see tufty ears and forgive the pointy nose? On balance though, based on the numbers but with some reservations, I’m going to give the badger his cute badge.

I’m not sure the Germans would agree though. A more oblique cuteness indicator mentioned by Gould, but one I like if only for its reminder of that mouthful of letters Germans use for squirrel – Eichhörnchen – is the wider association of the German diminutive form with certain animals and not others. So there’s also Rotkehlchen for Robin and Kaninchen for rabbit – all officially cute animals. I wonder if the trend follows in other countries using a diminutive suffix? Anyways, the Germans have nicht so honored the badger, who’s a plain simple Dachs (the origin of Dachshund, no less). I’m making my own stories up now, but have just too many Germans  been bitten by (rabid or otherwise) Dachs? Is the Dachs ‘one of Germany’s best-loved animals’ ? Guinea pigs are off the cute scale, but Peruvians don’t lose sleep over serving them up for lunch.

been bitten by (rabid or otherwise) Dachs? Is the Dachs ‘one of Germany’s best-loved animals’ ? Guinea pigs are off the cute scale, but Peruvians don’t lose sleep over serving them up for lunch.

And what do North Americans make of their badger, with it’s somewhat skunky appearance? (To my eyes, the American badger is actually flatter faced and all-round cuter) And before I diss. skunks too far, remember Pepé Le Pew? – not a million miles off Mickey on the cute ratios. I don’t know how far Gould and Lorenz factored in cultural variables like these; could be an interesting research topic.

To wrap up then. On badgers, I suspect some folks do support them just because they’re cute, but I’m also sure many look rationally at the bigger picture. Aside from Gould’s criteria, perhaps we should just ask ourselves if, under similar circumstances, we’d put the same effort into saving the poor old Purple Burrowing Frog?

At end though, any improved awareness of factors that influence our thoughts and actions, but are outside our immediate consciousness, is valuable. That’s what Gould is doing. I’m just relaying the message and expanding it a bit.

I also like badgers. And gibbons.

References

Mickey Mouse meets Konrad Lorenz. Natural History 1979, 88 (May): 30-36.

At the Planetary Society Blog, HERE, Melissa Rice tests the appearance of NASA’s now defunct Mars rover Spirit against the same Gould cuteness criteria discussed in the post. Fantastic!