Just a bit of fun really; but I’ve been mugging up on the basics of CGI. Things sure have moved on from the days of Muybridge and flip books ! Here’s my first attempt:

Movie made in DAZ Studio 4.6 with Animate2 plug-in.

Just a bit of fun really; but I’ve been mugging up on the basics of CGI. Things sure have moved on from the days of Muybridge and flip books ! Here’s my first attempt:

Movie made in DAZ Studio 4.6 with Animate2 plug-in.

You never know what unexpected quirky stuff is going to show up if you keep your eyes open.

This afternoon, Erin and I visited the Pasadena Museum of California Art to see an exhibition of works by Edgar Payne. We’re both fans of American plein-air painting, and Payne was a master of the technique – so the exhibition was a great success. But parking up, we found the Museum’s garage had its own artistic charm.

The graffiti is by artist Kenny Scharf, and instantly caught my eye with its images of rocket ships and swirling galaxies. The garage – or Kosmic Kavern – is the colorful legacy of an exhibition of Scharf’s work in the gallery proper in 2004 – his graffiti in the garage was just never cleaned off! Scharf’s work is influenced by the 1962 animated comedy sit-com The Jetsons, and there are other bits of space and nuclear iconography from the Golden Age of American Science spotted around – like the mushroom cloud and atom-swirl.

Some of the Jetson’s techno-utopia became a reality. But not, unfortunately, the aerocar or three-day week.

More Kenny Scharf

If you’d like to see more of his Kenny Scharf’s work, there’s a good collection at Artsy’s Kenny Scharf Page

Of related interest on Zoonomian

The fantastic weather in Oxford yesterday meant museum visits took a back seat to a good punting session on the Cherwell (a violation of physics in its own right with me at the helm).

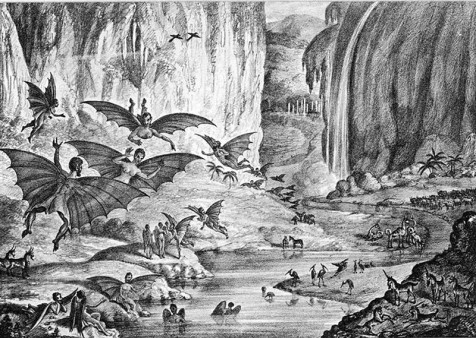

But we did get a half hour in the Museum of the History of Science , where I snapped this papier mache box lid, a great early example of newspapers not letting facts get in the way of a good story. For what they lacked in hacking scandals in 1835, they made up for in hoaxing, in stories like the one to which this exhibit relates: The Great Moon Hoax.

The picture is a satirical sketch of the astronomer Sir John Herschel, in a scene based on a series of reports by Richard Adams Locke for the New York Sun in 1835, supposedly describing observations made by Herschel at his South Africa observatory.

You can read up on the detail at the museum of hoaxes), but in this rendition, which is new to me, I particularly like the weird equipment combo Herschel’s minions are wielding around him: some sort of camera obscura / microscope mash-up by the looks of things. Maybe those instruments were more familiar than telescopes? Or, more likely, the journo just let his imagination get the better of him. Either way, I guess it’s still the little winged moon-men that steal the show.

The exhibit put me in mind of two lectures on a similar tack I enjoyed in the Royal Society’s History of Science series. You might like to check them out:

‘Fleas, lice, and an elephant on the moon’ by Dr Felicity Henderson (Sept 24 2010)

‘The Telescope at 400: a Satirical Journey’ by Richard Dunn (April 24 2009)

(both can be found by tracking down to the correct dates at the Royal Society podcast/vidcast page here).

When Nature Materials asked if I would write a Commentary on how I saw virtual worlds impacting our lives and science in particular, I was more than happy to share my thoughts. You can access the Commentary(1) and accompanying Editorial(2) by Joerg Heber in the December edition of Nature Materials. The following earlier draft on which the commentary is based, will I hope give Zoonomian readers unfamiliar with virtual worlds a broad introduction to some of their strengths, weaknesses and future potential.

Imagine an online phenomenon that you can engage with today, but which in ten years time will be bigger than the web, run on an infrastructure that makes Google’s hardware look like a pocket calculator, and can already deliver productivity and efficiency gains running into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. You would be there for that – right?

Well – maybe. Because despite some futuristic projections and perhaps a little wishful thinking, we are still not seeing full-on mainstream engagement with virtual worlds: the three-dimensional immersive environments where, video game style, you use a mouse and keyboard to walk and talk your personal avatar around a simulated world.

Yet recent numbers coming out of Linden Lab, owners of the dominant simulation Second Life, give pause for thought. For starters, Linden Lab say the virtual economy based on the in-world exchange of goods and services is now running at the equivalent of $500,000,000 per year. (Linden’s own income derives from virtual land sales and rentals, and virtual-real currency exchange.) Then there is the continuing enthusiasm shown for virtual worlds by big name business users like IBM, Sun and Intel – some of whom have developed their own simulations; and the host of educational and cultural institutions busily setting up their virtual shop, of which the University of Texas is the most recent and sizable example.

So what do the 70,000 or so users typically online in Second Life represent – a small entrenched community, or a portent of paradigm change in the nature of online human interaction? And what are they all doing there anyhow?

Based on my virtual wanderings, I can safely assure you that most Second Life residents are not visualizing scientific data, developing business strategies, or attending conferences and virtual universities. No – they’re mostly just having fun dressing up and forming a variety of friendships and relationships with real people projected into a fantasy setting. They’re also creating some magnificent artwork. I’m all for experiment – so good luck to them.

My own excitement about virtual worlds relates more to serious applications than fancy dress, reflecting perhaps my past life in physical and mathematical fluids modelling, or the sympathy I have as a former private pilot for flight simulation. I’m a recent convert, having discovered virtual worlds only last year while scanning for new and unusual science communication tools. Basic Second Life membership is free but, keen to establish a presence and experiment with building techniques, it wasn’t long before I’d purchased the modest plot of virtual land needed to do that. My initiation was complete when I met up with a team from Imperial College using virtual worlds for medical training – more of which later.

Yet mine is a minority interest. Even within my real-world community of science communicators, barely a handful of colleagues have avatars, and virtual worlds are only now starting to figure in the curriculum of science communication courses. Contacts in the UK museums sector likewise give the impression they are in no rush to engage – the argument being that the public are just not equipped or interested.

So what is the perception of users? Geeky at best. That the purpose of virtual relationships can be sexual (use your imagination) is a mixed blessing for Linden Lab: attracting some users and scaring others away. Recent measures taken to separate adult content should improve the balance.

What might it take then for virtual worlds to really take off? Can we expect another Facebook or Twitter-style growth event any time soon? Well, ask yourself why anyone might take the virtual leap? People engage where they perceive value, and that perception changes with perspective. The socialite or keen party animal, scientist, manager, and communicator will each focus on, understand, and value different aspects of virtual worlds.

First, there is a fundamental quality to virtual worlds that makes their use so attractive and could be the key driver for mainstream uptake. This special quality is a sense of space and, strange to say, something akin to a feeling of physical presence. That experience is enhanced by directional audio, such that you can hear footsteps behind you and voices get louder as avatars approach. Regrettably, this defining quality is also the most difficult to convey – you really have to experience it, which is worth remembering if you ever have to sell the concept. Significantly, those implementing the University of Texas Systems’s virtual university – covering 16 campuses no less – cite how important it was for part of their pitch to the sponsor Chancellors to be made in Second Life itself.

Talking points

I have been most impressed by the present and potential role for virtual worlds in education, and more generally as a platform for presentations and even full-blown conferencing. The many hundreds of educational establishments represented in Second Life, including major universities, attest to a pervasive interest in applying virtual worlds to learning. The arrival of large scale, well funded, projects like the Texas University System pilot, which has a research program for systematized knowledge capture built in, illustrates just how serious the ‘game’ of Second Life has become. From pilot studies like this will flow the best practices, methodologies and protocols on which the virtual universities of the not too distant future will operate.

For conferencing, substitution of the many experiences that make up a real-world event is unrealistic, but that still leaves scope for one-off lectures, classroom-less teaching scenarios, and those occasions where the trade-off of a virtual presence outweighs having no representation at all.

A good example is the Solo09 Science Online conference, organised in August this year, that ran simultaneously in real life at the UK’s Royal Institution in London – where I was sitting – and in Second Life for anybody who couldn’t make the venue. Virtual attendees participated fully in the discussions, and one of the speakers joined from Second Life. And importantly, the cameras were set so that we could all see each other.

The events I have joined have mostly been technically flawless, although the occasional outright disaster illustrates the danger of relaxing real world conference planning standards. Bad planning of virtual world events damages not only the organiser’s reputation but, in these early days, the credibility of the concept. Third party providers like Second Nature and Rivers Run Red with their Immersive Workspaces Solution are offering services to help clients get it right first time.

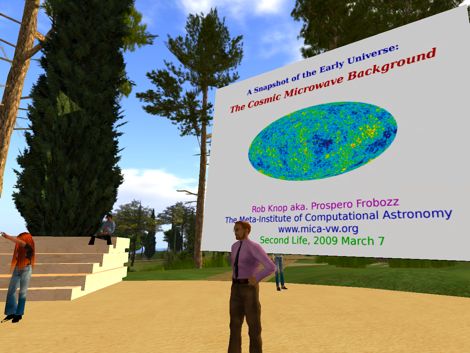

In the context of public lectures, there is a unique type of speaker-audience dynamic at work in virtual worlds that I really like, whereby protocol has somehow evolved such that audience members can comment and question, via a communal text box, during the presentation itself.

This would be pretty rude behaviour in the real world, but virtual speakers in the know seem to engage with it well, taking comments as cues to amplify audience points or elaborate on areas of the talk where there is special interest.

On the other hand, I have a real problem with the absence of any meaningful facial expression on avatars. We take expressions for granted in real life, but they deliver a lot of conscious and subconscious information that is simply lost in virtual reality. Next time you are at a real world event, make a mental note of where you are looking – it will not be the guy’s shoes. And I’m not impressed by the counter argument that expressionless anonymity makes strangers less intimidating to approach.

Good starting points for your first virtual public lecture are Second Nature at the Elucian Islands complex, NASA’s Education Island in the science rich apelago known as the SciLands, and for both public and more specialised professional astronomy talks – the Meta Institute for Computational Astrophysics (MICA). A list of science-related locations in SL can be found at this Science Center Wiki.

Private individuals and companies can hold their own virtual meetings and mini-conferences, which is a boon for geographically dispersed teams that need to work collaboratively. The benefits come through as reduced travel time, budget, and carbon footprint – with Intel claiming savings of $265,000 against one real-world meeting. Yet I suspect many traditional corporate managements are struggling to see the benefit of virtual worlds over good video-conferencing; and I do not envy anyone charged with selling virtual worlds to an unenthusiastic management.

The virtual versions of traditional collaboration aids that exist in Second Life, such as whiteboards and laser pointers, are good for highlighting features on slides and building basic flowcharts,but will disappoint those expecting the spontaneity of a flipchart. Yet workarounds that integrate ‘conventional’ two dimensional collaboration tools are possible, and we should remember that for the display of complex three dimensional objects – that can be walked around and entered – virtual worlds represent an improvement over real life. This kind of functionality is attractive to product designers, scientists, and engineers alike. A civil engineer might share a new bridge concept with a focus group, while an automotive designer might explore a vehicle prototype concept or visualise crash simulations.

In a purely commercial role, I can only envisage the most mechanical and uncontentious negotiations taking place across a virtual table; but that still leaves plenty of scope for collaborative activities including product and supply chain development. (IBM holds its most sensitive meetings behind a firewall in their own virtual world, and Linden Lab have just released a special ‘Enterprise’ version of Second Life for businesses.)

Scientific visualisations

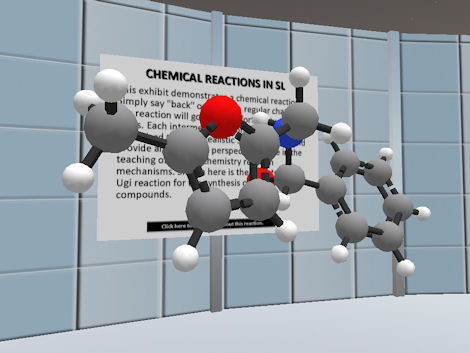

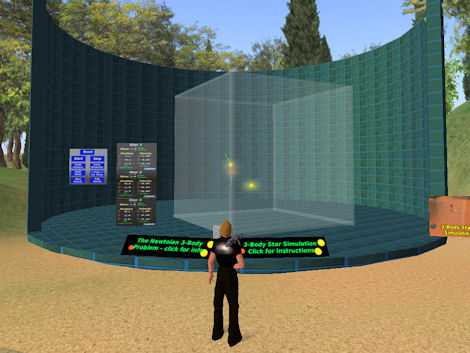

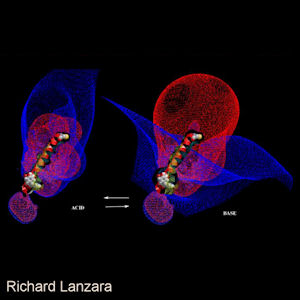

Data visualisation and simulation are core functionalities in the virtual world where, in the scientific sphere, chemists manipulate complex molecules, climatologists visualise weather systems, and astrophysicists simulate stellar motion.

Modeling of fundamental physical phenomena in Second Life is constrained by the limitations of the simulation’s HAVOK physics model which, designed to support the games and movie industries, is only partly faithful to the laws of physics. Some tweaking is possible, but complex simulations require that visualisations be tied in to external processing. For example, mass in Second Life is independent of material composition but increases uniformly with object size. Different materials exhibit levels of ’slipperiness’ approximating to friction – yet viscosity and buoyancy are not represented. The delays in processing large amounts of information make accurate real time simulation problematic.

To explore the possibilities of data visualization for yourself, you might set up a multi-body star system simulation with the help of MICA, or get up close and personal with some carbon nanotubes at the UK National Physical Laboratories nanoscience and nanotechnology hub in the NanoLands.

Public engagement

Virtual worlds are opening up new vistas in public engagement, ranging from the use of interactive but primarily educational displays and visualizations, through to immersive virtual consultations that impact real world policy-making.

A good example of the former is the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s presence in Second Life, where visitors can select weather systems from the Earth and other planets, and see them displayed on a giant walk-around globe – complete with audio commentary. While at NASA, the visitor can inspect and be photographed sitting atop a full size reproduction of a Saturn V launch vehicle.

A good example of virtual engagement informing real world policy is the London Strategic Health Authority’s project in association with Imperial College, involving a virtual hospital of the future that members of the public can experience and comment on.

My most memorable virtual experience happened on this campus, when I found myself guiding and chatting with some of the 1000 or so visitors who had appeared from all over the world for an open day. Such an assembly of individuals – with the multitude of interests, professions, and languages they represented – could only happen in virtual reality. I’ve blogged about this aspect of virtual worlds before, and you can listen to the short radio documentary I made at the time here:

That event showcased techniques for the training of medical professionals, but virtual worlds are also used for direct patient treatment. It is thought stress levels in patients facing surgery can be reduced by walking them through procedures ahead of time. And for the psychologically disturbed, virtual worlds can provide a controllable, non-threatening environment in which their condition can be monitored and improved – a technique the US military has used to gain a better understanding of combat stress.

The future

While the limited processing power of users’ computers prevents an immediate Twitter-style boom in avatar births, I firmly believe we will see huge growth in both the application and awareness of virtual worlds over the next two to five years.

As hardware costs fall and broadband becomes ubiquitous, the themes of integration and interface will dominate the technical and cultural horizons of virtual worlds.

Technically, a closer integration with communications and social media applications like Facebook, Twitter, Skype, and Google has already started; for example, I can now tweet from inside Second Life. At Second Earth, a ‘mash-up’ of Google Earth data with Second Life visualization is signposting the way ahead.

An inevitable move to more open standards will free avatars and virtual goods to move between different virtual worlds and other media platforms. The underlying physics models will improve, as will graphics and display technology. We will control our avatars via sensors that attach to, or remotely scan, our body and face; or we might use our brainwaves directly.

Culturally, we may find our daily routine moving seamlessly between the real and virtual worlds, in a future where avatars look and move exactly like their real world counterparts. Throwing off geek status, virtual worlds will become mainstream as more scientists, teachers, engineers, business people – and even some politicians – recognize the possibilities they offer.

All of which makes now a great time to put prejudice aside, get ahead of the game, and start checking out some of the amazing creative content and ideas that await you in the virtual universe.

Update 7/7/20011 – The Zoonomian Science Centre is no longer active, but you can still contact me in Second Life as Erasmus Magic. Or or course drop me a real-life email from the blog.

Tim Jones’s name in Second Life is Erasmus Magic

References

(1) ‘Getting real about our virtual future‘ in Nature Materials 8, 919 – 921 (2009)

doi:10.1038/nmat2580

(2) Editorial in Nature Materials 8, 917 (2009)

doi:10.1038/nmat2582

Related Links

Joanna Scott’s retrospective on the SOLO09 conference here at Nature Network

Update / Other Info

The Dutch Royal Academy of Arts and Science ‘Jonge Akademie’ invited me to talk about the themes covered in this paper and virtual worlds in general. Here are the slides from the event.

August 2010 – Linden’s attempt at a business only product just didn’t work for them. Interesting analysis here at Hypergridbusiness.com, including comments from IBM.

Update March 2024: The Exquisite Corpse project is closed to further entries.

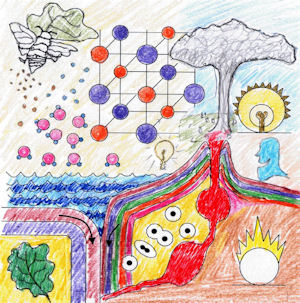

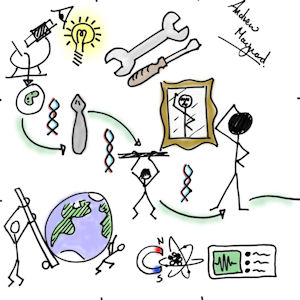

It’s just over a week since I invited the world to take part in the Exquisite Corpse of Science project. It’s very simple: you send me a picture that represents what you think is important about science, and as an option you can add a short audio file describing what you’ve drawn.

I’ll then combine these into a single artwork in the manner of the Surrealists’ Exquisite Corpse – and further present the project in ‘fly-around’ 3D in Second Life. A couple of high profile events have shown interest in relaying this project – so no promises – but watch this space.

So how’s it going? Well the original post has had over a thousand hits, and the enthusiasm for the idea from individuals and organisations involved in science and science communication is encouraging.

Twitter seems to be the main vehicle by which word is getting around. Many thanks to those who have blogged on the project, and Twitter friends who are promoting it via the infamous ‘Re-Tweet’; especially: Andrew Maynard & family @2020science, @frogst, @imperialspark,@garethm (BBC Digital Planet),@vye, and the organisations @seedmag (SEED Magazine), @naturenews (via Matt Brown/@maxine_clarke), @sciandthecity (NY Academy of Sciences), and @the_leonardo in Utah. Also, thanks to Dave Taylor (@nanodave) at Imperial College – who is working with me on the Second Life virtual incarnation of Exquisite Corpse.

I want to doubly stress that the Exquisite Corpse Of Science is most definitely not just for scientists and engineers; it’s for literally everybody. And it’s absolutely not about producing a Leonardo or Rembrandt……So get your Gran’ma on the case.

I’ve so far received 11pictures (+ 7 more I know are in the pipeline), and 4 audio accompaniments. So keep the pics coming in to make the definitive ‘WALL OF SCIENCE’ big and beautiful. Come on guys, how can I inspire you ! I know, the pictures so far….

This post is a little different from anything I’ve put up before. It’s a sort of blog-ised version of an academic semiotic analysis I made earlier in the year as part of my Science Communication endeavours at Imperial College. It’s here thanks to a posting on Twitter earlier tonight by Chris Anderson (of TED fame) of an alert to David Hoffman’s film now on YouTube: ‘The Sputnik Moment – the Year America Changed its Schools’. It’s all about how Sputnik, launched on October 4th 1957, shocked the USA into massive investment in, and reform of, the education system. I’ve embedded the vid at the end of this post.

What follows is not directly linked to Sputnik; it refers to the previous year – 1956, but does perhaps remind us that the wheels were already turning towards a golden age of science. And I guess that made the advent of Sputnik all the more shocking.

If you’re not familiar with the techniques of semiotic analysis (I certainly wasn’t), it can look a little contrived. But be assured, there are folk out there right now using it to design stuff that will subtly manipulate you. It’s not evil – but I think it’s useful and fun to practice deconstructing these things. Anyhow, if you get bored, just skip to Hoffman’s vid :-). So…

Home Chemistry in the Golden Age of American Science

“And so each citizen plays an indispensable role. The productivity of our heads, our hands, and our hearts is the source of all the strength we can command, for both the enrichment of our lives and the winning of the peace.”

So proclaimed U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower in his First Inaugural Address of 1953[1] – emboldening a populace who, through the experience of science and technology at war, knew the peaceful role it might play in delivering America’s future.

And it’s to this background ethos of goal achievement and individual contribution that we’ll learn in this short essay how the innocuous chemistry set punched above its weight in preparing the nation’s youth for the golden age of American science.

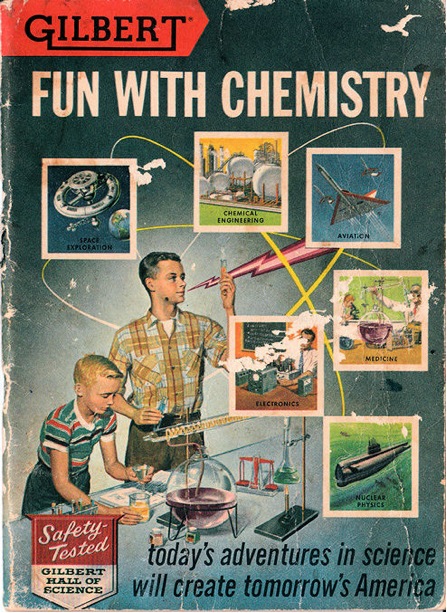

For a deeper insight into what that meant in 1950s’ America, I’m going to look beyond the obvious, and pass a semiotician’s eye over, or maybe under, the cover-art of an instruction manual to a 1956 A.C.Gilbert Experiment Lab.

The idea is to start with a review of what the picture denotes – what is explicitly shown. The aim of the semiotic approach is then to explore the less obvious and wider connotations of the picture, treating it as a ‘text’ that tells a certain story – to which the embedded and inter-related vignettes also contribute. We need to remember this is a story of, and in, its time – and it’s only going to make sense in the cultural context of the period. Likewise, any connotations need to be interpreted in terms of the meanings and ideologies that might have engaged a contemporary reader.

That’s the approach – so what next? Every good semiotic analysis needs a formal argument if it’s not to fly totally off the tracks. So, I’m going to argue that:

‘marketing texts accompanying 1950’s American chemistry sets were consciously designed to support the myth of American progress achievable through an ideology of military and industrial global leadership; and contributed to an environment, the underlying ideology of which Eisenhower would in 1961 articulate as the ‘military-industrial complex’[2]’.

(some folk have found my double reference to Eisenhower’s speeches confusing – so to clarify: The first reference is to his inaugural speech, the second is to his statement in his farewell address, where he first mentions the (in)famous ‘military-industrial-complex’. The point is that the MIC wasn’t something Eisenhower set out intentionally to put in place; rather it was something he realised had pretty much evolved by the end of his term – and was something to be concerned about.)

On with the analysis of the picture….

With reference to popular images from the great American telescopes of the day[3], a hazy nebular against a dark blue sky forms the backdrop to iconic representations of the Rutherford-model atom whirl and a cartoon electric thunderbolt. Two boys, maybe 10 and 14 years of age, do chemistry experiments at a bench. Six small graphic vignettes arc around the boys, each denoting a real or imagined scene from one of: space exploration, chemical engineering, aviation, medicine, nuclear physics, and electronics. A white capitalised title banner: ‘FUN WITH CHEMISTRY’, and a more reserved strap line: ‘today’s adventures in science will create tomorrow’s America’, frame the page top and bottom. A small maker’s logo and red safety shield complete the picture.

First Impressions

The eye immediately tracks to the boys, particularly the elder boy. We’re helped by his central positioning; and the electric thunderbolt, symbolic as pointer in one direction and megaphone in the other, placed contiguous with his mouth. The presence of two boys connotes camaraderie, but also hints at paternalistic leadership by the elder – a theme enhanced by their dress and respective positions (smaller boy leans forward, elder stands) and engagements (younger boy stirs, older boy analyses).

More perhaps from the parents’ viewpoint, the scene connotes an ideal of family life, reminding the reader of the vulnerability of a harmony so recently recovered from the disruption of war (US engagement in Korea until 1953). From the child’s perspective, domestic clutter has been erased – leaving a brave future world in which the boys are abstractly suspended between deep space and the exciting promise of the vignettes – the whole entangled with the modernity of the atom whirl.

A Golden Career

Qualifying traits to enter this world are symbolised by the boy’s trim haircut and white vest – connoting military order, responsible self-discipline, and an appeal to conformity in an America struggling with McCarthian legacy[4]. The manual itself is symbolic of instruction and procedure; worry not – there is a plan.

Correctly, the boys do not laugh stupidly over their toy, but exude a serene dignity and confidence in the handling of their equipment; imagery that would endear any paying parent to Gilbert’s product. And where the parent approves, the young owner idolises – the elder boy: god-like before nebulae, proclaiming through lightning, holding forth with test-tube as sceptre.

The ideals put upon the boys are echoed and reinforced by the white coated, neck-tied exemplars of the medical and electronics vignettes, their adjustments and measurements further connoting values of care and precision. (The absence of personal protective equipment for the boys reminds us they are not yet professionals.)

For the world of the vignettes is where Gilbert Experiment Lab owners are destined to go. In his mind, the contemporary teenager leaves home through this text’s imagery, entering an educational way-station toward an ordained industrial career in ‘tomorrow’s America’ and the Golden Age of Science. A golden age, defined by exponential consumerism, a highways programme that would drive automobile and refinery demand for the next twenty years, and an age of popular successes in American chemistry (DDT) and medicine (Jonas’s polio vaccine).

Gilbert and his main competitor, Porter Chemcraft, reinforced the career message to both parent and child through explicit statements in associated texts[5] ; for example, the rear box cover of the Experiment Lab displayed the banner:

“Another Gilbert Career-Building Science Set”

While Porter Chemcraft’s box banner pulled no punches with:

“Porter Science Prepares Young America for World Leadership”

The Vignettes – Windows on the Military-Industrial Complex?

Given their importance to the whole, the vignettes warrant closer examination. Taken individually they denote aspects, both realistic (submarine) and speculative (space station), of their respective industries -but achieve more as elements of the greater text. For example, collectively they reference the shear pervasiveness of chemistry as a discipline across mankind’s endeavours. And (core to my argument), they variously reference the repeating themes of American dominance in the military, industrial, and aerospace fields – politically prescribed activities for the ‘enrichment of lives and winning of peace’[6].

On a technical level we can acknowledge the clever use of white borders around the vignettes, signifying them as real photographs, fooling us that even obviously speculative scenes represent real life captured.

For a contemporary reader, the wheel-like space station of the space exploration vignette provokes a strong reference to Wernher Von Braun’s 1952 conception of a navigation-military platform [7].

The scene would also be familiar from science fiction texts, both print and film, and space programme news items anticipating the first US earth-orbiting satellites (Explorer I launched in 1958).

The station dominates the globe of earth. A globe which itself is dominated by an American continental outline – a reference to the ideological exaggeration seen in the nation-flattering Rand McNally Mercator projections and consumer advertising copy of the period.[8]

The combined effect is to establish a concept of an America that, projected into space, is positioned to both dominate the earth in one direction and explore the cosmos in the other.

Beside the romance of space exploration, we might today frame as pedestrian the industrial world of chemical engineering; not so in 1956 America. Cropped of peripheral clutter, the spherical white pressure vessels become molecules – uniting with the boys’ glassware, the analytics of the medicine vignette, and the chemistry set itself, as icons of professional chemistry. Reference to the boys’ large flask is enhanced by that vessel’s exaggeration beyond anything actually found in the set, the parallel rendered complete by the rubber tubing imitating pipe and gantry.

The aviation and nuclear physics vignettes both denote forms of transport. The swept delta wing and compact size of the jet aircraft signifies a military product, while the streaming contrails index for progress, movement, speed – and power. The choice of submarine as nuclear physics exemplar, against the option of a civilian reactor or a particle physics laboratory, reinforces the military imperative. Directly referencing the recent launch of the first nuclear powered submarine Nautilus [9], the image flatters the reader’s knowledge of this event.

The vessel is large and dark, with whale-like power, its speed helpfully indexed by the artist as turbulence in the ocean streamlines. Like America, it is unstoppable and, as the scattering fish signify, all must make way before it.

A further subtle, yet reinforcing, reference to the defensive aspects of militarism can be read in the use of the red shield icon to frame the words ‘Safety-Tested’, whereby feelings of comfort and reassurance are induced on the twin planes of home and national security.

Military references are absent from the medical and electronic vignettes, these rather providing a visual link with the boys’ home activity. The medical scientist’s equipment mirrors the boys’ rig – right down to the colour of liquid in the flask. The electronic laboratory’s blackboard is an iconic reference to scientific intellectualism and progressive theory, but also a familiar reference to the boys’ schoolroom blackboard. The inclusion of medicine as a theme is a calculated reference to improvements in health and quality of life – the ultimate public justification for industrial and military progress.

The predominant portrayal of individual human actors in the vignettes promotes an inaccurate myth of scientist as lone worker, at a time when the power of teamwork, recently exemplified by the Manhattan Project, was widely recognised. A more realistic representation may simply have been viewed as overcomplicating or jeopardising of the text structures used to link home and career.

Other Features – Stereotyping

The apparent gender and racial stereotyping through omission is alerting to our modern eye, but typical of the day. A fairer representation of gender, but never balance, is evident in later texts such as the 1960 Golden Book of Chemistry[10] – itself an icon of the genre – where boys and girls are seen working together both at home and in the professional laboratory.

Race would certainly be the basis for an oppositional reading of this text. Despite the Immigration & Naturalisation Act of 1952, supposedly removing racial and ethnic barriers to citizenship, and the banning of racial segregation in schools in 1954, a black readership would likely receive Gilbert’s racially exclusive offering as just another slam of the door to white privilege.

Conclusion

Gibson could have produced his chemistry manuals with plain covers; they would certainly have appeared business like and practical. Yet that would disallow, as this analysis has shown, an induction into, and repeated reminders of, the world of work and modern America to which the set promised entry. A world of progress, Gilbert’s artwork tells us – with its speeding aircraft and submarines, and the restless whirl of the electron.

We have revealed evidence of Gilbert’s subscription to an ideology of American global leadership. And how, by integrating military and industrial images, and linking them through themes of progress and the pervasiveness of chemistry, he expertly references the whole to the domestic life and career ambition of his customer. In doing so, Gilbert, representing a substantial share of the 1950s chemistry set market, endorses my core argument.

[1] Dwight D. Eisenhower First Inaugural Address, (January 20, 1953)

[2] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Farewell Address (January 17, 1961)

[3] The Hale 200 inch telescope was first operated in 1948; eight years earlier. See: Florence, Ronald. The perfect machine: building the Palomar telescope, Harper Perrenial 1995

[4] Although McCarthy was ostracised two years earlier in1954, the threat of communist conspiracy and suspicion of outsiders or the unusual remained

[5] Nicholls, Henry. The chemistry set generation, Chemistry World Dec. 2007

[6] Ibid 1 Eisenhower

[7] Von Braun’s Wheel. NASA Archives. http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap960302.html

[8] A schoolroom series of maps by Rand McNally placed America centrally on the globe and split the former soviet union in two. See: George Simmons, ‘Training with map power’ in Cultural Detective at http://www.culturaldetective.com/worldmaps.html

[9] U.S. Navy Submarine Force Museum, http://www.ussnautilus.org/index.html

[10] Brent, Robert. The Golden Book of Chemistry, Golden Press New York, 1960

Here is David Hoffman’s film

Also of interest:

Cold War in the Classroom – Harvard Univ. Dept History of Science Exhibition 2011

Various Chemistry Set related Web-links:

Twelve Angry Men Blog – ‘Endangered Species – the Chemistry Set’

Twelve Angry Men Blog – ‘Endangered Species – the Chemistry Set – Sightings in the Wild”

Royal Society of Chemistry – ‘The Chemistry Set Generation’

Notes from the Technology Underground – ‘Gilbert Atomic Energy Lab’

I’ve just returned from the annual British Humanist Association Darwin Day Lecture, this year delivered by Sir David King at a session chaired by Richard Dawkins.

King is a former Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK Government, and now heads up a multi-disciplinary organisation tackling climate change – The Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment- at Oxford University.

His talk entitled ‘Can British Science Rise to the New Challenges of the Twenty First Century?’ was very similar in content to one I watched him give at a PAWS event in November, and dealt less with British Science, and more with the complexities of tackling global climate change. There were some new angles, but I’d refer you to my previous blog HERE – inspired by Sir David’s earlier talk – rather than repeat myself. I believe a podcast of tonight’s event will appear on the BHA site in due course.

So perhaps, given the greater relevance to current debate over poor media reporting of science, and particularly that related to MMR (and the Goldacre/LBC radio encounter), you’d like to hear what Sir David volunteered tonight on that subject. It came up in response to a question from the floor about the Daily Mail. Sir David’s transposed response:

“We’ve now got a measles epidemic growing in this country, and the measles epidemic is the result directly of a very poor piece of science from John Wakefield, somehow being published in the Lancet – should never have been published – the database was far too small. And then gaining momentum in the media, and it’s not only the Daily Mail, John Humphreys was one of those pushing that… that the connection between MMR and autism raised real questions, and the take-up of the MMR vaccine began to fall very dramatically. And my prediction a few years ago was that we would approach something like a hundred deaths a year from, amongst children, from measles as a measles outbreak occured, inevitably.

If you do models and you drop below 80% uptake of the vaccine, the measles must come back. Of course the Daily Mail’s campaign was one of the instruments that got people very worried about that particular issue. So I think that was an example where the science was so clear. Let me tell you. There was a Danish study of all the children born in Denmark over ten years of whom 15% had not had the MMR vaccine, and 85% had. The statistical incidence of autism in the two groups was the same. Now just to be on the…on the…..when I say the same within statistical error. The nice thing was, from the point of view of those who were sceptics, that amongst the group who didn’t have the vaccine, there was a slight larger number- larger percentage – with autism. Now any parent worrying about the situation, just needs surely to be given that set of statistics, and yet the Daily Mail wouldn’t publish it when I went to them. What am I saying, [finding his words]well, it rarely gets their story right. There is…there is a sort of disbelief, but I’m afraid when a newspaper is running a campaign, there’s very little can stop the train”

To which Richard Dawkins, with a look of amazement and with apparent reference to the Daily Mail not printing the Denmark evidence, said – “I’m shocked”