Today is the birthday of the inventor of nitroglycerin: Ascanio Sobrero.

Born on 12th October, 1812, the Italian chemist made the discovery while a student at Turin University, by treating glycerin with hot sulphuric and nitric acids.

The industrial and military successes of nitroglycerin are well known, particularly where it’s been used in stabilised forms as in Alfred Nobel’s patent dynamite. Less well known is the catalogue of horrific accidents that punctuate the early learning curve of this powerful explosive.

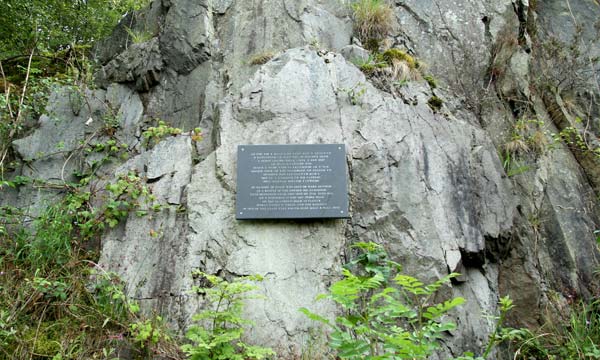

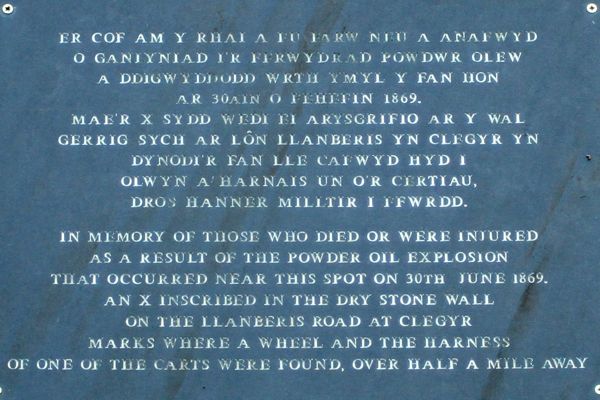

I stumbled upon the echo of one such tragedy while holidaying in Wales this summer. A lucky stumble too, as the plaque that records the Cwm-y-Glo explosion of 1869 is easy to miss: only locals and wandering hikers need apply.

It’s unlikely David Roberts, Evan Jones, Robert Morris, Griffith Jones, and eleven year old John Jones had heard of Ascanio Sobrero. Likewise the villagers who collected those victims’ unidentifiable remains after Sobrero’s invention sent them flying in pieces onto the hillside and surrounding villages.

The two horse-drawn wagons at the centre of the disaster, each laden with a ton of nitroglycerin, or ‘powder oil’, were on the eight mile journey from Caernarvon, on the Welsh coast, to the Glyn Rhonwy slate quarry near Llanberis.

The cargo was destined to blast slate, but when it exploded prematurely just outside the small village where its minders had stopped for refreshment, it likely created the loudest man-made noise known up to that time. And despite Glyn Rhonwy being one of the first quarries to trial nitroglycerin1starting in 1866, they clearly hadn’t mastered the murderous sensitivity of its handling. The full report of the accident as it appeared in The Times newspaper is reproduced in reference 4 below – with all the gory details.

View Cwm y Glo Explosion Plaque in a larger map

The political and economic impact of the Cwm-y-Glo explosion travelled well beyond Wales. One direct consequence was the introduction of the Nitro-glycerine Act (1869)(reproduced as ref(3) below): “An Act to prohibit for a limited period the importation, and to restrict and regulate the carriage of Nitro-glycerine“(2), which put severe controls on the explosive’s importation, transportation and use, and encouraged the market for safer alternatives like gun cotton (cellulose nitrate) and Nobel’s dynamite. Supposedly a temporary measure, during which time “there would be an opportunity given to scientific persons to inquire whether the compound known as nitro-glycerine was an innocent explosive or not.“(2), the restrictions lasted long enough to prompt heated debates around ideas of trade restriction and monopoly.

But the local impact was human, as the following ballad from the time shows. I’ve had a crack at translating the first few verses from the Welsh (with my father’s help!) – just to get the gist. The author, Abel Jones, seems to be catching the brutal reality of the event in true Victorian style. You can find the whole piece here. (And, if you’re able and up for it, feel free to translate the whole thing and put it in the comments!)

“A ballad about a terrible explosion that happened in 1869 at Cwm y glo.

Dear quarrymen and all rockworkers throughout Arfon and Meirionydd. Hear about this alarming and terrible accident that has made many hearts sad. There has been accident after accident in the quarries, with falling loose rocks from morning to noon. They tear the flesh and break the bones and people collect bodies in blankets and sheets. What heart does not melt at the sight of a mother unable to recognise her son or husband, the tears pouring from the children shouting: ‘Dad, where are you?’. And things are far worse with nitro-glycerine. We’ve had terrible disasters at Abergele, now we have one at Cwm y glo ”

And the original Welsh:

Ger Abergele bu g’lau asdra

References

(1) Alfred Nobel in Scotland John E Dolan, Nobelprize.org

(2) New Statesman, Commons Debates 1873, The Nitro-Glycerine Act (1869)

ref(3)

4. A report of the accident in The Times

The Times, July 2, 1869

The Nitro-Glycerine Accident. CARNARVON, Thursday.

The terrible accident we reported yesterday by telegraph has led to lamentable results. It seems that four tons of nitro-glycerine formed part of a cargo from Hamburg (Messrs. Noble and Co.), to Carnarvon, consigned to Messrs. De Winton and Co., for Messrs. Webb and Cragg, Glynrhonwy Slate Quarry, Llanberis, sole agents in Carnarvonshire for nitro-glycerine, used instead of ordinary powder for blasting rocks. The ship was moored in the river Menai, and a portion of the explosive oil having been placed in the Llanddwyn magazine, the rest was brought in lighters and placed on the quay in Carnarvon. About 1 o’clock noon, the hour appointed to cart that portion to the quarries, some of the vehicles did not arrive, and, after a delay of some hours, the two carters who have been killed under- took to remove a portion of the nitro-glycerine. These carts left about 4 on Wednesday afternoon, for Glyn-rhonwy Quarry, one of the numerous quarries lately opened on the south aspect of the Vale of LIanberis, and at the foot of Snowdon. A portion of the nitro-glycerine was to be removed today to the Dinorwic Quarry. The other three carts were left for the night in a closed coachhouse, near Bodenalgate, within a mile of Carnarvon, it being too late to re- move the oil to the Penrhyn slate quarries. These are now in the custody of the police. The two carts which caused the accident, were, it appears, in company, and were noticed within a few yards of each other just be- fore the explosion. The exact spot where the accident occurred is where the diversion of a new road lately made by the Llanberis and Carnarvon Railway joins the old road, about 400 yards beyond the centre of Cwm-y-glo village, five miles and a half from Carnarvon and 300 yards from Pont Rhyddalit, the bridge that spans the narrow water uniting the upper and lower lakes of Llanberis. At the time the accident occurred the quarrymen were returning along the road from their occupations to Cwm.y-glo village, when suddenly, without any warning, the quarrymen in front of the carts and those behind heard one long continuous explosion of terrific noise. This spot being surrounded by high mountains on three sides, the echo of the first explosion reverberated several times, as some of those that witnessed the accident informed us, and one mountain seemed to throw the noise with quick succession from one side of. the valley to the other over the lakes. The two lakes, especially the lower, were at once greatly agitated. Clouds of dust, stones, portions of the carts, and the walls around for two roods were either thrown to a great height or cast longitudinally either into the morass on one side or the rocks adjacent. A third of the circumference of a wheel was thrown 50 yards high and fell near a cottager’s garden on the sides of a rocky hill 300 yards off. Portions of flesh and bones (either human or those of the horses) were collected indiscriminately from a radius of 50 yards and placed in cloths. A foot, a chin covered with beard, and a man’s heart were found together about eight yards from the spot. The Cwm-y-glo Railway Station (the nearest building to the scene of the accident), an inn lately finished, close by, and several (fortunately) unfinished houses a little further off, as well as a chapel, present a desolate sight. The roofs nearest the accident are perforated by falling stones, and window- frames have been blown in and destroyed. The massive doors of the goods department of the railway station are shattered, and windows all round within a radius of two miles present marks of the explosion. Scores of men were thrown down. Those known to be killed are -David Roberts, 35. a native of Denbigh, married, carter; Evan Jones, 22, Tyddyn Llywdyn, Carnarvon, unmarried (son of a widow, partially dependent on her son), carter; Robert Roberts, 26, quarryman (who had only returned from America a few weeks since); a quarryman who was supposed to be passing at the time,.and another whose name we could not ascertain resident at Cwm-y-glo. About 12 persons have been seriously hurt and as many slightly injured. A leg and in two other instances arms have already been amputated, and two boys-Owen John Roberts and Griffith Pritchard have suffered internal injuries by being thrown down. The greatest distress exists, and even this morning the police were engaged searching the neighbourhood of the accident picking up very small portions of flesh and bone. Such was the terrible power of the oil that the spot where each cart is supposed to have been at the time of the accident is marked by two deep perfectly circular holes, of the same size, each measuring 7ft. 6in. in diameter and 7ft. deep, and a horse-length apart. The stones appear to have been subjected to a terrible rotatory motion, and the holes are in the shape of an inverted cone. Our correspondent, who was at the time of the accident sitting at a friend’s table in Bangor, ten miles off, experienced a shock and heard the rattling of windows at five minutes before 6, about the time fixed by those who witnessed the, accident. The shock was experienced more or less for many miles around.

Other sources