(This article originally appeared at conservationtoday.org)

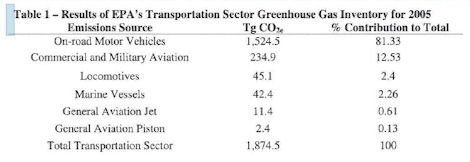

Over Christmas, according to the Carbon Neutral Company’s online calculator, my wife and I were responsible for the release of 4.2 tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere – our share of a 19000km round trip flight from London to Los Angeles. With two such flights a year, that makes our individual emission 4.2 tonnes, or nearly half the UK per person annual average of 9.51 tonnes.

To reel off excuses for this travel (my better half hails from the US, and we like to see the in-laws in the flesh occasionally) is to miss the point, which is that I, and many more like me, at least now have some awareness and quantification of the impact we’re making; our consciousness has been raised.

We’re all part of the problem, each with our own circumstances, and each needing a plan to address our impact. My plan might involve paying the Carbon Neutral Company’s recommended carbon off-set fee of £35.70 in support of a Chinese hydro-electric project. It won’t on this occasion, because while I support off-setting as one tool in the bag of control measures, I’ve chosen instead to donate to projects benefiting animals already affected by the complex interplay of climate factors – which I’m about to come on to.

Starting the year with a knowledge of your personal carbon footprint is only part of the story. While sufficient perhaps for the average citizen to act upon and make a difference, policy makers, industry leaders, NGOs, conservationists, educators, and the plethora of other stakeholders and interest groups directly involved in climate change issues, need the bigger picture.

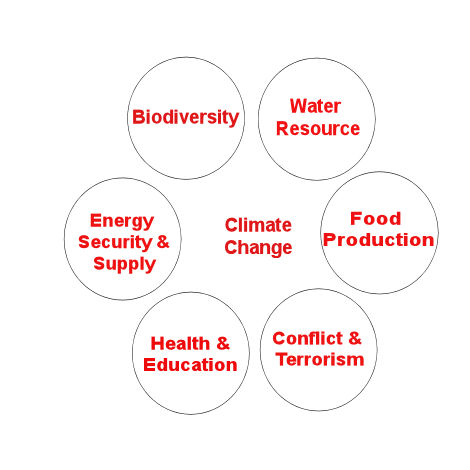

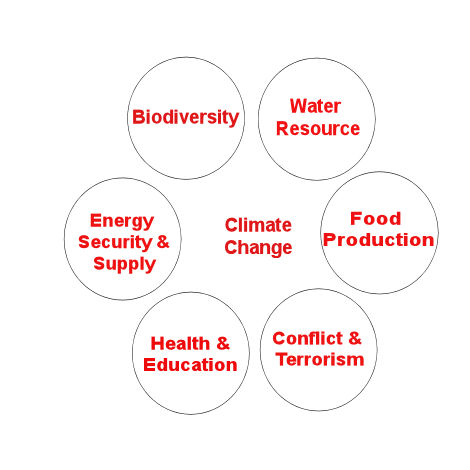

This is the bigger picture I’ll be working to in 2009, and it comes from the UK Government’s former Chief Scientific Advisor – Sir David King. It’s been in my head, sparking ideas and resonating with a whole range of experience since I scribbled it on the back of a business card back in November. I saw Sir David at an environmental media awards evening organised by PAWS, where he used the diagram to illustrate the important challenges of the 21st Century, and their inter-dependency.

Examples of specific inter-dependencies are well represented in Conservation Today articles: from unpredictable climate induced pathogen interactions impacting biodiversity, to corporate actions influencing food production, to how health and education are changing the global population dynamic. King’s representation is helpful in encapsulating the whole smash; its something you can carry around in your mental back pocket. Away from specifics, it also for me informs at least three more oblique, but no less important, themes that I’ll now expand upon:

- The importance of not generalising

- The imperative for interdisciplinary and international cooperation

- An opportunity for business and an alternative to rampant consumerism?

Don’t Generalise

I’ll illustrate how generalisations are dangerous with reference to two processes: desalination and GM crop growing.

Desalination is a process that has been criticised for its energy intensity and associated CO2 footprint. King referred to the Australian province of Victoria’s response to seven years of drought conditions, whereby a third of its water will in future come from new desalination capacity. Ultimately powered by Australia’s plentiful coal reserves, the plants will indirectly yield CO2, which will warm the planet, which will intensify the drought, which will demand more desalination plants. It’s a simplified picture – but you get the point; in this case technology is a short term fix to a grim spiral.

I’ve since though found a more positive example of ‘Green Desalination’ in the form of California’s Carlsbad Project. Here, a 50 million gallon per day desalination plant is being built to supply up to 8% of San Diego County’s water needs, involving co-location of the plant with a new power station at the coast. The encouraging part is that when completed in 2011, it promises to be the first US plant to have a net zero carbon footprint.

So why can the Americans do it but not the Australians? First off – don’t generalise – every situation is different; processes and power stations are not inherently evil. San Diego County currently imports 90 percent of its water from a distance of more than 800km, from Sacramento Bay Delta and Colorado River, and the electricity needed to deliver and treat that water is close to what the new plant will use. The mitigation of the remaining ‘CO2 gap’ will be achieved at the site through initiatives like green building design; on-site solar power generation; funding renewables; and acquisition of renewable energy credits. Further carbon dioxide will be sequestrated by creation of coastal wetlands and reforestation (we know how important those are, see here) – and that will impact biodiversity. See how our diagram is working here?

We also generalise when we impose the luxury of our western standards on to less wealthy societies. Increased desertification and flooding in some Asian regions is combining with a healthier, more educated, and therefore at least temporarily increasing, population, to demand that rice farming become more intensive. This means farming on land that may flood, requiring flood resistant rice strains – which are readily available as GM seeds. In practice though, farmers wishing to export product beyond their own needs refrain from using GM rice because of the negative attitude it attracts in the west. As a result, such farms may fail to meet even local food needs. Given my personal stance on GM crops, that amounts to a case of “one man’s lifestyle choice is another man’s starvation”.

The imperative for interdisciplinary and international cooperation

Inter-relating challenges demand an increased coordination of the political, infrastructure, research, and educational aspects associated with each. Global warming is possibly the defining example of a need for innovatory thinking combined with an imperative for pan-disciplinary co-operation; not only across the sciences, but involving engineering, medicine, commercial, and policy elements. The slow progress made at recent climate summits suggests the required international policy infrastructure just does not exist. So where are the rays of hope? The world has high hopes of Obama, and his promised global energy forum could be part of a more mature future; remember this:

“In addition I will create a Global Energy Forum—based on the G8+5, which includes all G-8 members plus Brazil, China, India, Mexico and South Africa—comprising the largest energy consuming nations from both the developed and developing world. This forum would focus exclusively on global energy and environmental issues. I will also create a Technology Transfer Program dedicated to exporting climate-friendly technologies, including green buildings, clean coal and advanced automobiles, to developing countries to help them combat climate change”

And closer to home, encouraging exemplar organisations have emerged, such as the University College London’s Environment Institute, who are developing a pan-disciplinary approach to global warming; and King’s own organisation, the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment in Oxford, which aims to help governments, companies, and individuals meet future environmental challenges in the context of the bigger picture.

An opportunity for business and an alternative to rampant consumption

I could easily have overprinted the big picture interactions diagram with a giant $ sign, given that all our challenges are inescapably embedded in an economic and political web of capitalist growth imperative, feeding on consumption and wealth generation. Question is – has that web, via the present financial crisis and to a background of increased environmental awareness, had a wake up call in any positive sense?

I’m going to stick my neck out and take an upbeat, even optimistic, tack on how business and the capitalist monster can become our greatest assest in tackling the century’s environmental challenges. How come? Because I believe there will be a significant shift of attitudes in (a) business awareness of the opportunities from environment related projects (like the Carlsbad desalination scheme), (b) increased government investment in such projects, both as a way of countering recession and addressing the underlying environmental need, (c) a less predictable re-think on the part of private individuals about the role of consumption – particularly excessive consumption in the west – on their well-being. I’m most optimistic about (a) and (b), precisely because the required technologies and management practices are at present so underdeveloped. I’m less sure about the form of, or optimistic about how we might achieve, the revised international infrastructure needed to moderate individual nation’s interests.