Having unaccountably failed to spot comet McNaught on its recent visit, I was compensated last week by a meeting with this artificial comet created at the Griffith Observatory .

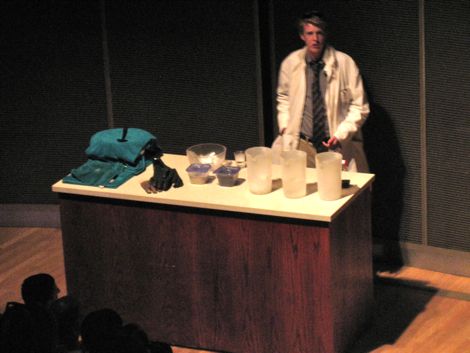

Demonstrator Grace is holding the tangible product of last Friday’s ‘Let’s Make A Comet’ event, held in the Griffith’s Leonard Nimoy Event Horizon Theatre. And I have to say, it was one of the best half hour’s worth of science communication I’ve seen.

I think the shear fun value had a lot to do with it. And although the show was geared to a young audience, there was no dumbing down of the science or talking down to the kids. Presentation style and jokes were witty rather than silly, patronising, or childish; and references to popular culture, like Harry Potter and the Transformers movie, were entertaining but topic-related. The professionalism of the two demonstrators / presenters really made the show, and it’s taking nothing away from the scientific knowledge and skills these guys have, to say they were genuine entertainers.

The comet was made by mixing together common substances containing the elements found in real comets. So that meant shaking up water, sand, carbon, and cleaning fluid (ammonia) together with dry-ice, or frozen CO2, in a plastic bag; the details are here on Griffith’s Teacher Resources page.

I liked the hidden plan to pull an audience in on the promise of seeing a comet being made, then to educate them on broader themes and related topics; the practical demonstration happening only at the end of the session. There was nothing sinister in that though, and it all went down well with the bulk of the show taken up with a mix of talk, slides, videos and Q&A breaks. A lot of ground was covered, ranging from the chemical and physical requirements for life, to how the solar system is thought to have formed, and a pretty good introduction to astrobiology – including a discussion of extremophile life-forms.

Lecture theatre events are inevitably going to be a little one-way, but there was good engagement through the Q&As and frequent questions back to the audience. And it’s not like this was a public consultation on the risks of nanotechnology, the material being relatively uncontroversial.

Having the finished item available for inspection after the show was a big plus, and I’m sure the memory of it will for many people be a lasting anchor for the science they picked up.