Just a bit of fun really; but I’ve been mugging up on the basics of CGI. Things sure have moved on from the days of Muybridge and flip books ! Here’s my first attempt:

Movie made in DAZ Studio 4.6 with Animate2 plug-in.

Just a bit of fun really; but I’ve been mugging up on the basics of CGI. Things sure have moved on from the days of Muybridge and flip books ! Here’s my first attempt:

Movie made in DAZ Studio 4.6 with Animate2 plug-in.

Quite a cold afternoon’s walk today; but the sun was up, the golfers were out, and so too were our local herons. I snapped this one just before sunset. He’s a Grey Heron (Aredea cinerea) and common in the UK. (I keep an eye out for the Blue Heron and super-rare Purple Heron, that occasionally visit the UK, but have seen neither.)

Herons nest in colonies, and this one looked like it contained three birds: two adults flying back and forth to the nest, and a smaller ‘second winter’ juvenile that stayed put (the one on the left of the pair in these shots).

I was surprised to see nest-building this time of year, but the hardy heron’s extended breeding season sees them happily dropping eggs in late February. That’s not to say the smaller bird here is a chick – they leave the nest by 10 weeks, and this one’s plumage is too mature. I’m guessing it just wasn’t his/her shift for twig collection.

They’re fantastic birds to watch. Very noisy and, to my eyes, especially dinosaury. I also like the retracted neck position adopted for steady flight; it’s like their head goes along for the ride in upper-deck business class. It’s also one way to tell herons apart from cranes.

The Heron’s nest is a large flat platform of twigs in the top of a tree. The males do most of the collecting, the females most of the building.

These last two shots of the nest show an adult bird on the right, and what I suspect is a ‘second winter’ juvenile on the left (tell me if you think differently). Despite the stance, there was no feeding going on here.

It’s days like this that justify carrying heavy cameras and lenses around on the off-chance something might show up. Next phase is to return with the tripod and get some HD movies of these guys. Watch this space!

I took these photographs between 5.00 and 6.15 a.m., 10th December 2011, from the foothills above Los Angeles near Pasadena. Here’s the progression through to totality at around 6.05 a.m.

With a diameter of 120,000 kilometres and a bright reflective surface, Saturn is an unmissable object in the night sky right now. But at 1.3 billion kilometres away from us, it looks only a hundreth the size of the full moon. Which means the screen width of my Saturn video below represents one third of a lunar diameter across (for best view, click to full screen):

[jwplayer mediaid=”9786″]

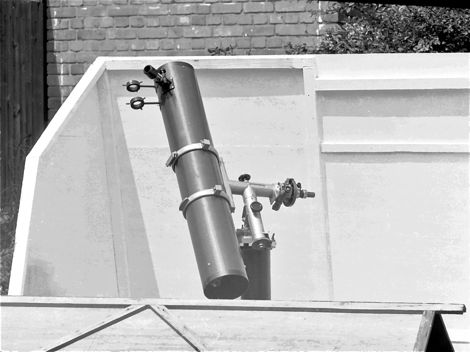

I recorded the movie through my old but capable 1978-vintage 6″ Fullerscopes reflector – specially resurrected for Easter after 30 years in storage. (See my efforts with the moon and the smaller ETX-90 telescope in Armchair Astronomy.)

Getting the telescope up and running really required nothing more than (literally) brushing away some cobwebs and giving the mirrors a wash – something I’d be more hesitant of doing had I not just read a step-by-step ‘how to’ in Sky at Night magazine.

Although thick with dust and grime, I’d reason to believe the mirrors’ coatings beneath were o.k., as I remember having them vacuum re-aluminised and silica coated just before I abandoned the instrument and disappeared off to university. Some gentle soaking, swabbing, and rinsing down with distilled water, and all was shiny once again.

Fullerscopes’ german equatorial mountings were all built like tanks – this ‘Mark II’, rated to carry a 10″ reflector, is still in good order save for some rust on the exposed steel shafts.

The RA drive, that ordinarily would drive the telescope counter-rotational to the Earth’s axis, wasn’t operational for a variety of reasons; but the fine adjustment on the declination axis was working.

All of which goes to explain why on the clip Saturn appears to fly across the screen.

I’d forgotten how stunning to the eye Saturn is through this telescope. In better seeing conditions I’ve seen the gap in the rings – the Cassini Division – quite clearly. Now, Saturn’s moon Titan was unmistakable.

Filming what you see with your eye is a little more challenging, although the ‘live view’ on the Canon 7D makes life a lot easier. Rather than watch the live feed through a computer, on this occasion I used the camera’s LCD display directly to focus with the help of a magnifying glass. The clip was made by projecting the image onto the camera’s CCD sensor via a 12.5mm orthoscopic eyepiece; the main mirror’s focal length is about 1250mm. The scene could have stood higher magnification, but I was limited by the eyepiece focal length and size of the projection tube.

All in all, considering the state of the equipment at the start of the day, I’m happy with the end result. The gap between the disk of Saturn and the rings is clear enough; but no Cassini division – so still some work to do! All the same, a fun day messing around with telescopes and engineering – no better way to spend the Easter hols.

2. To be exact: the angular size of Saturn on 25/4/2011 was 19 seconds (“) of arc, approximately a third of a minute. There are 60 seconds in a minute, and the moon is typically 30 minutes across; so Saturn appears one ninetieth of the moons diameter.

Through a combination of photography and a creeping fascination with avian behaviour and taxonomy (thanks to my wife giving me Colin Tudge’s The Secret Life of Birds for my birthday) I think I’m turning into some sort of accidental ornithologist. Point being, you can expect the occasional photo-flavoured birdy post; and today – it’s woodpeckers!

The female Eurasian Green Woodpecker (Picus viridis) above is one of the three most common woodpeckers found in the UK .

Photographically, woodpeckers are a challenge. The whole family is jumpy, taking off as a matter of principle at the sniff of a threat. So, considering I was sneaking up with no hide, I’m pleased how these turned out. Here are a few more of the male/female pair and a juvenile. You can tell the male by the red flash under his eye (click thumbnail to open slideshow):

And this male Great Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocopos major)was snapped only a few days ago (click thumbnail to open slideshow):

Globally, there are 218 species4 in the Picidae family to which woodpeckers belong, living in every country with trees except for Australia and New Zealand.

Here are two more I snapped in California. The first set shows an Acorn Woodpecker Melanenpes formicivorus and the Ladder-backed Woodpecker Picoides scalaris (click thumbnail to open slideshow):

Here’s a video of a female Ladder-back hunting for bugs:

Acorn Woodpeckers are expert at turning trees into communal larders or caches. Pecking thousands of small pits in a single tree, they’ll place an acorn in each one – ready for harder times.

This set, again taken in California, is of a female Williamson’s Sapsucker – a member of the family specialising in eating the sap out of small wells drilled into the bark of pine trees:

Woodpeckers are a wonderful showcase for evolutionary adaptation.

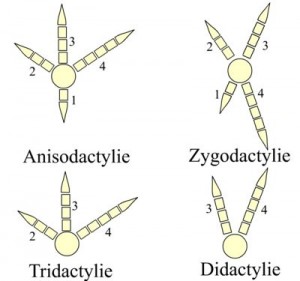

Sharp claws set on toes laid out in the zygodactylous pattern – two toes facing forward, two back – are ideal for tree climbing. (Parrots and cuckoos are set up similarly, and elsewhere in the animal kingdom – Chameleons.)

Then there’s the way they hold themselves on the tree trunk.

Like rock climbers and photographers favour three points of contact for security and stability, woodpeckers have evolved a stiff tail to brace against the tree trunk and make a sturdy triangle with their splayed legs. The Sapsucker below demonstrates nicely; you can see her two tail quills bending under the pressure.

Having formed this miniaturised drilling platform, woodpeckers set-to doing their thing, which for a Ladder-backed woodpecker is banging its beak into bark and wood at up to 28 times a second, repeating the act several hundred times a day1.

The aim is to locate and consume insects and sap from under tree bark, a task for which their long, barbed tongue is well suited. But as this Great Spotted demonstrates, the birds are not above pecking the ground if there are bugs and termites to be had.

As hole-dwellers, woodpeckers also peck to hollow out a nest – a process that can take up to a month and involve the removal of tens of thousands of wood chips4.

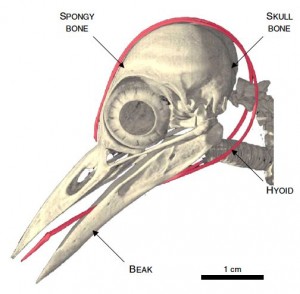

For me, the woodpeckers’ most impressive adaptation is the multi-element shock absorber system that’s developed in and around its skull to prevent brain damage from all that bashing.

The full complexity of the system has only recently come to light. X-rays of a woodpecker’s head showed that the massive deceleration occuring at beak strike is cushioned and spread out thanks to elasticity in the beak, a spongy area of bone at the front of the skull, and a further special structure – the Hyoid – that directs pressure from the rear of the birds tongue around the back of its head1.

Well that’s a wrap on woodpeckers for the moment. Next phase is to try and catch these guys on HD video; they’re doing some great little courting dances this time of year. Reaches for camouflage gear….

References and further reading

1) A mechanical analysis of woodpecker drumming and its application to shock-absorbing systems. Sang-Hee Yoon and Sungmin Park 2011 Bioinspir. Biomim. 6 016003 IOP Publishing doi: 10.1088/1748-3182/6/1/016003

2) Digital Morphology. (Images at: http://digimorph.org/specimens/Melanerpes_aurifrons/)

3) Birds of Europe. Mullarney, Svenson, Zetterstrom, Grant. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN-13: 978-0-691-05053-9

4) The Secret Life of Birds. Tudge, Colin, Penguin, 2008.

5) Cornell Lab of Ornithology – All About Birds (Woodpecker page)

Also of interest?

It’s a good few years since I took a photograph through a telescope, so I thought I’d share my latest pics.

The moon’s been presenting itself as a nice late evening target in our Westerly outlook this week, so that’s where I’m starting. These two are the best of the bunch from the last couple of nights (click for bigger pictures):

And in this video clip taken by eyepiece projection, there’s quite a bit of detail visible in the Mare Criseum (Sea-of-Crises) at top left:

[quicktime]https://communicatescience.com/zoonomian/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Moon_astro_7_4_11_eyepieceprojection2.m4v[/quicktime]

This longer clip shows a complete traverse of the moon across the field of view (no tracking):

[quicktime]https://communicatescience.com/zoonomian/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Moon_astro_7_4_11.m4v[/quicktime]

I’m particularly pleased with how the videos came out, capturing the fleeting moments of still air you need to look out for when observing live by eye.

The rig is built around an ultra-compact Meade ETX-90 telescope, picked up when I moved to London 10 years ago as a more suitable replacement for my 6 inch reflector. All I’ve added is a connecting tube and T-mount to get the camera hitched up.

Strictly speaking, you don’t need a telescope for astrophotography. Here’s the Plough (Big Dipper) taken with a tripod-mounted standard lens:

And these shots of an Earthlit Moon and Venus are two of my favourites:

I’ve also had some luck in the middle ground using telephoto lenses, where the results have been surprisingly good: like these pics of a lunar eclipse, the International Space Station (ISS), and Jupiter with its moons; all taken with a 400mm lens – in the case of the ISS, hand-held:

I’ve also had some luck in the middle ground using telephoto lenses, where the results have been surprisingly good: like these pics of a lunar eclipse, the International Space Station (ISS), and Jupiter with its moons; all taken with a 400mm lens – in the case of the ISS, hand-held:

18 megapixels of digital zoom helps resolve the ISS into something other than an unrecognisable blob.

But to resolve surface detail in objects like Jupiter, a true astronomical telescope is called for.

I started by simply holding my smartphone to the eyepiece. Not a disaster, but I lost fine detail and the moon took on a weird pinkish bloom.

Attaching a digital SLR directly to the telescope gave better results, with the camera’s CCD (Charge Coupled Device) sensor at the prime focus. I also experimented with an old Logitech webcam with the lens removed, but the background noise was too high and the small sensor size made for a very narrow field of view.

The Canon 7D gives a much nicer image, and can be operated totally remotely via the computer. Live images are fed to the laptop screen for easy focus and exposure control.

With the still pictures, I want to get to grips with the various image processing techniques for stacking multiple images.

Of course, none of this competes with the Hubble Space Telescope, but amateur astrophotography for me is more about the satisfaction of seeing what a particular instrument can do, and learning along the way more about the various objects I’m photographing.

After the moon, my next target is Saturn, with the goal of resolving the Cassini division in the rings; and Jupiter, where I’ll be happy if I can resolve the Great Red Spot.

I’m also planning to take some guided wide-field photos of deep sky objects like the Orion Nebula. But that requires dark skys and the telescope’s drives being sufficiently accurate and strong enough to support a ‘piggy-backed’ camera and lens. All for another day.

The immediate issue, as the videos show, is just how bad the ‘seeing’ can be when observing at dusk from a building that’s been baking in the sun all day. I need to find more open skys.

But for now, with the telescope’s motors whirring away on the balcony, I literally am the armchair astrophotographer.

There were literally a few seconds at sunrise this morning when the clouds stayed off long enough for me to catch this partial eclipse of the sun by the moon from a hilltop in Leicester, UK, at around 8.30.

It clouded over completely within ten minutes – and is now snowing. Fewer clouds would have been nice, but I consider myself lucky all the same. The limb of the moon is clearly visible. Following pics in chronological order.

SEE ALSO MY POST ON THE 20 May 2012 Annular Solar Eclipse HERE

Leicester University got a similar view: see here.

And some really nice pics from further afield in the Telegraph here.

Mark Edwards, near Rugby, had similar conditions to mine: here via BBC

Forget the turkey – RATS are the Christmas treat for this ravenous reynard.

I caught this juvenile fox in the garden this Christmas Eve morning enjoying a little pre-lunch entertainment courtesy of an unfortunate rodent. Very similar to watching a cat play with a mouse. Here’s the series:

Our star is currently promoting the forthcoming production of Ben Jonson’s Volpone by the Playing Up Theatre Company at the Rondo Theatre in Bath during February, where the Sly Fox has apparently developed a taste for chickens.

Of related interest…

Post by Ed Yong here at DISCOVER on how foxes might be using magnetism to help catch prey.

With snow now everywhere in the UK, it’s chilly enough to forget some of winter’s less obvious compensations – like the magnificent sunset I snapped this afternoon.

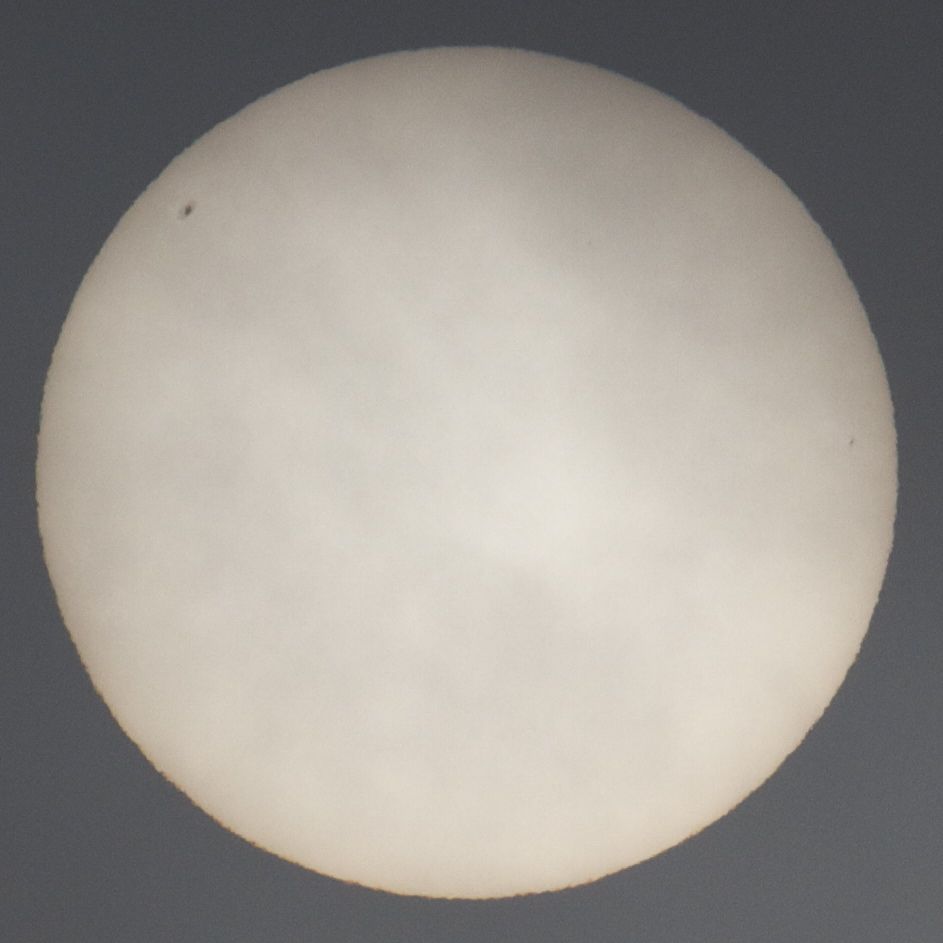

Under these sort of cloud conditions, the intensity of the sun’s light is reduced but its image remains sharp. It may even be possible to see large sunspot groups – if they’re there – with the naked eye. I wasn’t able to see anything with my naked eye on this occasion, but there is a small speck visible in the top left of the disk in the picture above. Through a 400mm lens, that speck looks like this:

The two parts of the spot, the umbra and penumbra at different temperatures, are clearly visible. There are actually a couple more very small sunspots visible on the full disk: click the picture below for a larger image:

All in all, not a bad afternoon’s improvised astronomy.

WARNING: As always with the sun, you should never look at it directly with any kind of optical instrument, and even staring directly at the sun with just your eyes can be dangerous. I took these pictures by pre-focusing to infinity and pointing the camera without looking directly at the sun’s disk, which was low in the sky at sunset and behind cloud. The safest way to view the sun and sunspots is to use a telescope to project their image onto a piece of paper.

Not all of them, you understand. But here’s a few I’ve snapped in and around Los Angeles, Santa Barbara and San Francisco on visits over the year.

NOTE: I”M RE-JIGGING THE SLIDE-SHOW RIGHT NOW. SORRY FOR ANY INCONVENIENCE.