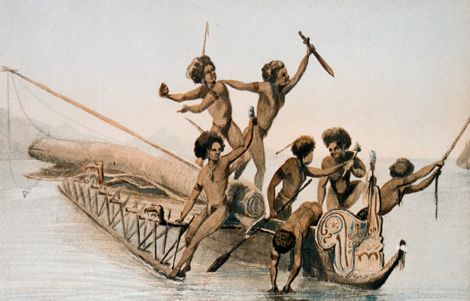

The Guardian this week reported on the UK Natural History Museum’s efforts to repatriate a collection of human bones, acquired by explorers in bygone years, to their original home with islanders in the Torres Straits.

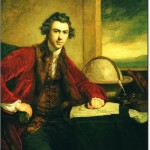

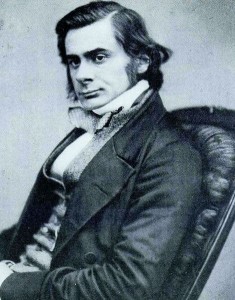

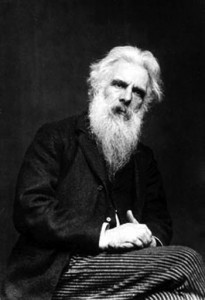

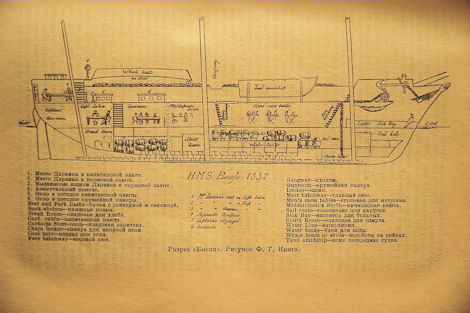

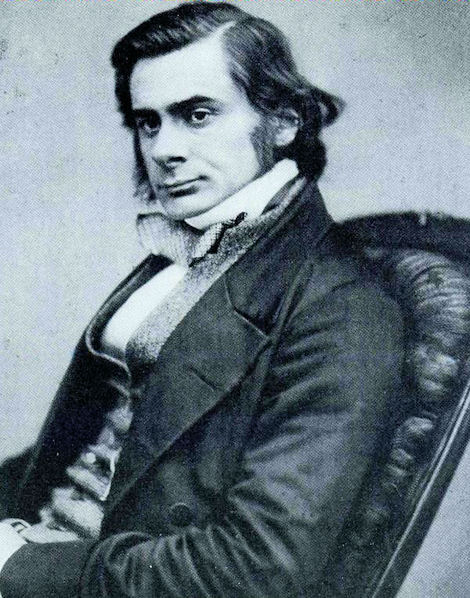

It’s not a piece I’d linger over save for the mention of H.M.S. Rattlesnake, a 19th century survey ship involved in, among other duties, the collection of anthropological specimens. Moreover, the Assistant-Surgeon on the 1846-50 voyage was the young Thomas Henry Huxley, very much cutting his teeth in hands-on nature study and ethnography.

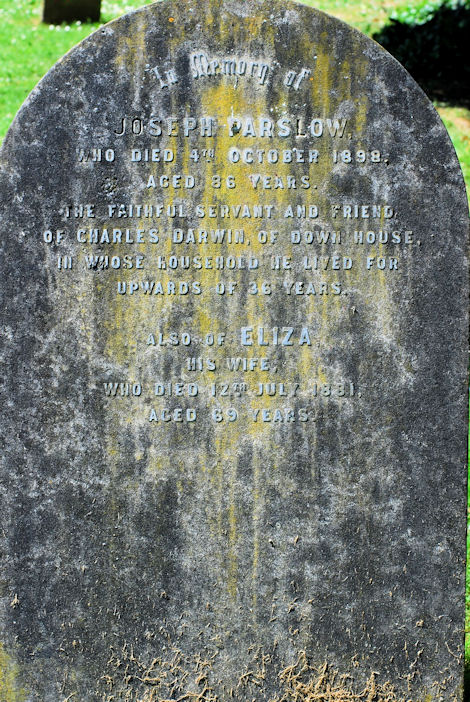

Regular readers will know I’m quite a fan of the man later known as ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’, so any association with what we now recognise as unsavoury cultural violations demands a look-see.

Huxley worked alongside ship’s Surgeon Dr Thompson and Naturalist John MacGillivray, under the overall command of Captain Owen Stanley.

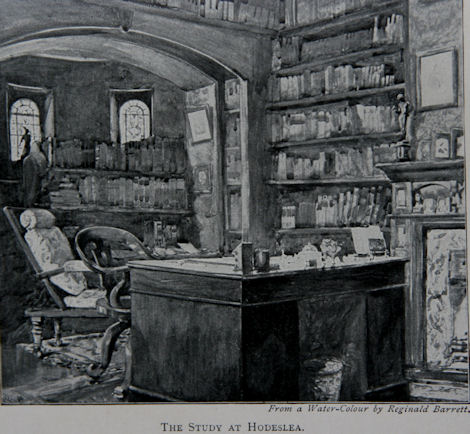

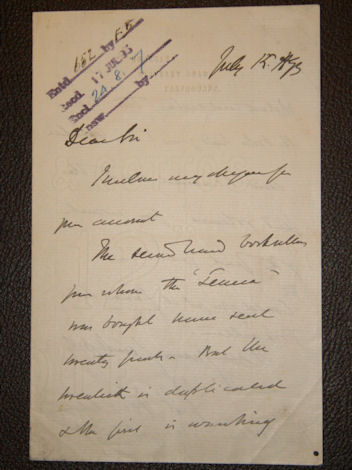

His Rattlesnake Diary, only published in 1935 by grandson Julian, captures thoughts and details of the voyage with a candour absent from more official reports.

The two diary entries that mention human artifacts, in this case a jaw bone bracelet, give some feel for the circumstances in which such pieces were obtained and the way Huxley spoke about the indigenous peoples.

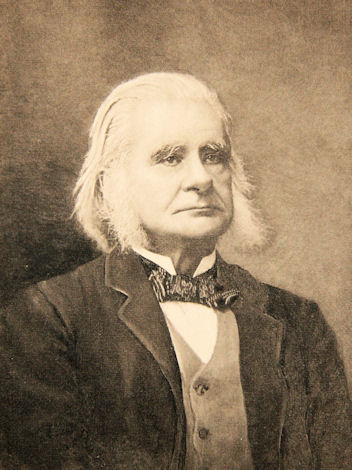

And as we have Julian Huxley’s thoughts on his grandfather’s behaviour (via his editorial commentary), there’s an opportunity to compare the ethics and cultural norms in anthropology not only between the mid-nineteenth century (when the bones were collected) and the present day (manifest in the Natural History Museum’s repatriation efforts), but also with the norms prevailing in 1935.

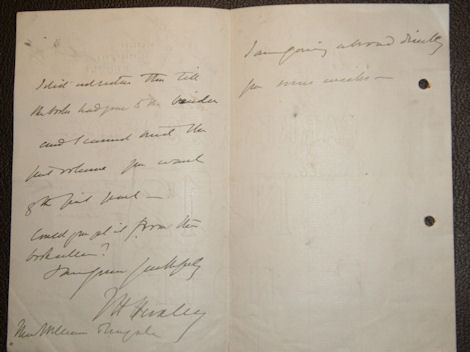

On to the diary entries. In June 1849, with the Rattlesnake anchored among the islands of the Louisade Archipelago, Huxley describes an apparent overnight change in the local people’s willingness to barter a jaw bone ornament:

24th. Sunday [June 1849]

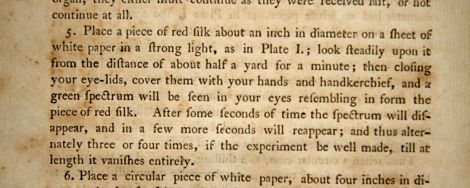

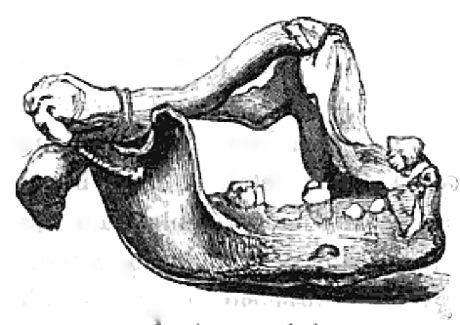

Huxley: “We had four or five canoes off to barter with us this morning – such squealing and shouting and laughing and yelling was never heard! One of the niggers had a human jaw by way of a bracelet. There was one tooth in the jaw and the circlet was completed by a smal bone apparently of some animal lashed to the coronoid process.

The old fellow would not part from it for love or money. Hatchets, looking-glasses, handkerchiefs, all were spurned and he seemed to think our attempts to get it rather absurd, turning to his fellows and jabbering, whereupon they all set up a great clamour, and laughed. Another jaw was seen soon in one of the canoes, so that it is possibly the custom there to ornament themselves with the memorials of friends or trophies of vanquished foes.” [Entry continues.]

Things have changed by the next day. Huxley doesn’t mention any additional enticements that might have been used to achieve this, although it’s clear from other parts of the diary that iron and tools were particularly valued:

25th. [Monday, June 1849]

Huxley: “Several canoes came off this morning; one of them brought the figure-head which was so much wanted yesterday, and bartered it immediately. In one of the canoes was a man with a jaw bracelet. The jaw was in fine preservation and evidently belonged to a young person, every tooth being entire. They seemed to have no scruple in selling it. A jade hatchet was procured from them also.” [Entry continues.]

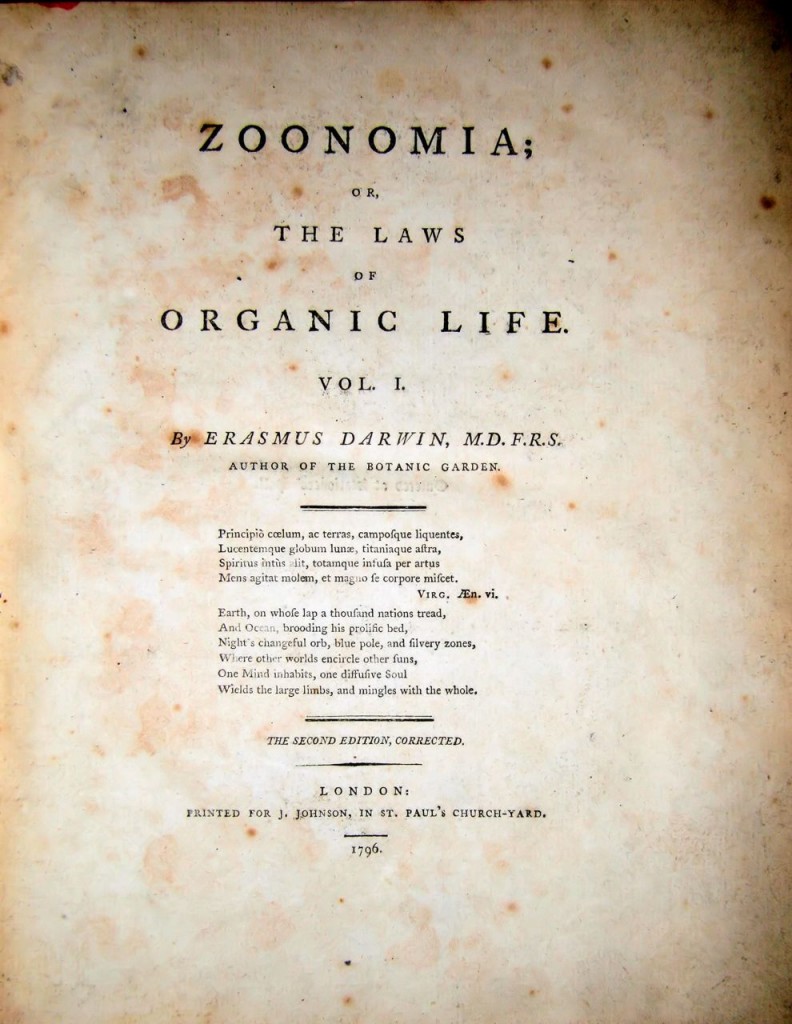

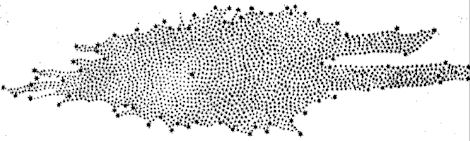

The jaw is also mentioned in a more formal report by MacGillivray in his Narrative of The Voyage of H.M.S.Rattlesnake (2) (And from which the drawing of the jaw bone above is taken.)

MacGillivray: “…But the most curious bracelet, and by no means an uncommon one, is that made of a lower human jaw with one or more collar bones closing the upper side crossing from one angle to another. Whether these are the jaws of former friends or enemies we had no means of ascertaining; no great value appeared to be attached to them; and it was observed, as a curious circumstance, that none of these jaws had the teeth discoloured by the practice of betel chewing.”

First off, Huxley’s vernacular is alarming to modern ears – and this from a bastion of 19th century intellectual enlightenment. Likewise, we wouldn’t by present standards in these circumstances take a willingness to hand over cultural artifacts as ethical licence to receive them.

Moving to Julian Huxley’s editorial. Introducing a chapter titled “Huxley and the Savages”, J.H. appears to be at pains to rationalise, if not apologise for, certain of T.H.’s behaviours, in doing so revealing his own predudices:

“He had none of the trained anthropologist’s insight into the black man’s mind, little conception of the alien ways of thought and feeling in which a primitive savage is enmeshed. His reactions were those of a generous-minded young man with plenty of common sense but a strong feeling for justice. He felt that there was some absolute standard of moral behaviour by which both the explorers and the natives could and should be judged. On the whole, he censured his white companions more hardly than the Papuans and Australian blacks.”

Although his views changed radically in later life, there’s a consistency here with Julian Huxley’s advocacy for Eugenic principles, a belief in the genetic basis for differences between human groups, and the concept of genetic inferiority. I read the passage as an oblique approval of T.H.’s egalitarian sense of justice, but with the suggestion he’s applied it through ignorance and an incorrect assumption that blacks and whites are fundamentally the same. One wonders what T.H. would say, had he the benefit of a time machine, in 1935? Would he ask his grandson, politely, to stay off his team?

From this example, it does start to look in some important respects like cultural attitudes in 1935 hadn’t progressed as much as one might think from those of Victorian times. And were museums still accepting human artifacts in 1935? (I suspect they were, but please speak up if you know). I doubt there was much repatriation of bones going on.

Well, that turned into something of a Huxley-bashing session afterall. In fairness, isolated diary extracts don’t give the most rounded impression of a person and, as I actually think the Rattlesnake diary does a particulary good job of that for Huxley, I’ll close by encouraging you to make a full reading (it’s not too long, very readable, and not at all boring).

Update 13.3.11 – Natural History Museum news release on the Torres Strait repatriation (10.3.11)

Update 6.5.11 – Torres Strait Island Community ancestral remains return begins and video

Update 23.11.11 Museum Returns 19 Ancestral Remains to Torres Straits Islanders (Natural History Museum)

Sources

(1) T.H.Huxley’s Diary of the Voyage of H.M.S. Rattlesnake. Ed. Julian Huxley, Chatto and Windus, London 1935

(2) Narrative of the voyage of H.M.S. Rattlesnake, commanded by the late Captain Owen Stanley during the years 1846-50

John MacGillivray, George Busk, Robert Gordon Latham, Edward Forbes, Adam White – 1852

(3) The Huxley File, Guide 2, Voyage of the Rattlesnake. Charles Blinderman, Clark University.

(4) Natural History Museum returns bones of 138 Torres Strait Islanders. Guardian newspaper, 10th March, 2011

Also of interest: Julian Huxley and the Invention of the Public Scientist (BBC Radio 4)

Photographs are taken from the author’s copy of T.H.Huxley’s Rattlesnake Diary and public domain sources.