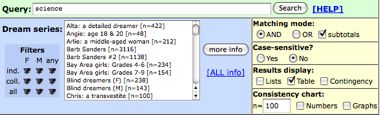

This picture of a Sinclair Scientific is the latest recovered image from the 30 year archive of negatives I’m dutifully working through.

The reflections in this post are also prompted by this recent post on Andrew Maynard’s blog, (2020science), describing the sophisticated graphing calculator his children are required to have for school.

A pass-me-down from my brother, the Sinclair Scientific was my first electronic calculator. Built from a kit in 1975, I used it to prep for the UK O-Levels when I was 14 or 15; in the O-Level exams themselves we only had log tables :-P. By the A-Levels (16-18), I’d upgraded to a Casio fx-39.

As it turns out, the calculator my nephews require for today’s GCSE syllabus is a Casio; but costing around £5, against the £75 or so for Andrew’s Texas Instruments machine.

An interesting feature of the Sinclair Scientific was its use of Reverse Polish Notation (RPN): an unusual but logical way to express calculations. Under RPN, the operator (+,- x, / etc) comes after the operands (the numbers); so the more well known Infix representation of 7+8 , in RPN becomes 7 8 +. RPN is more memory efficient for computers – a bigger deal once than it is now. Today, modern computers just translate into RPN without us seeing it.

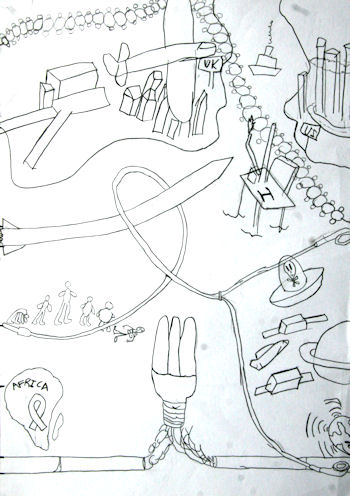

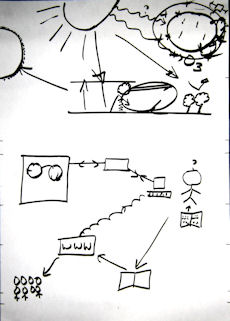

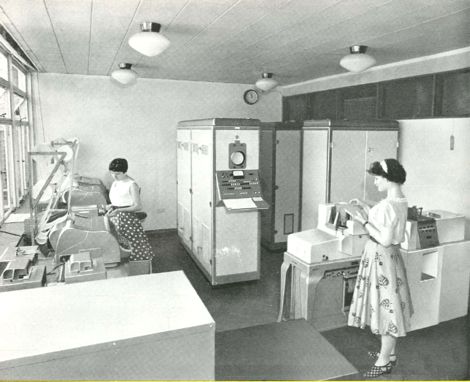

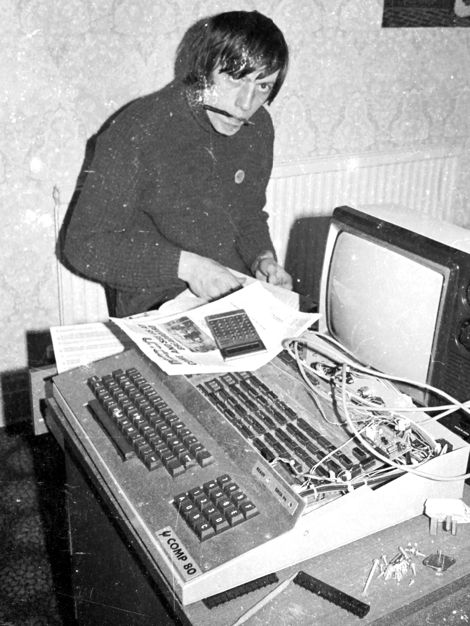

You might think getting to grips with RPN was an awkward distraction for a 15 year old, but it proved handy background when it came to writing programs for this:

I guess this was our graphing calculator. Not exactly pocket size.

If memory serves, my school, named the ‘The Gateway’, acquired the 1958 Stantec Zebra from the local university; before that it was with the Post Office.

A small team of students operated and maintained the machine which, filled with hot valves, would frequently catch fire and give the occasional electric shock. This could never happen today of course, on safety grounds alone. But at the time, the teachers and students took it all in their stride, seizing the opportunity to build a short extra-curricular programming course into the timetable.

Programming lessons involved: writing code on cards with pencil and paper, encryption onto punched cards that the Stantec Zebra could read optically, then receiving line-printer output of the results. Looking back, it’s amazing any of this happened – a great opportunistic use of a rare resource.

Pupils who later built their own computers, like the Science of Cambridge MK14, a basic kit machine launched in 1977 with about 2k of memory, or the Sinclair ZX-80, were doubtless inspired by the presence on site of their valve-driven (but still significantly more powerful) ancestor.

An interest in computers in this era meant just that: an interest in the information structure, solution algorithms, programming and hardware. High level programming languages, like BASIC even, were too memory inefficient to exist, and ‘games’ typically comprised simple models around the laws of motion; moon lander simulations were popular.

Our household variously hosted a home-built Powertran Comp 80, a Sharp MZ-80A (including some early green dot graphical capability), a Sinclair Spectrum and Sinclair QL. I’ve put pics of these and various other devices I’ve owned in the gallery at the end of the post – minus the obvious PCs that started with a Viglen P90 in 1995. Also our Creed 75 teleprinter – the only one I’ve seen outside the London Science Museum, this true electro-mechanical wonder was brought to good working order save for the chassis occasionally running live with mains voltage.

Are there any world-changing messages to be drawn from all this nostalgia? Possibly not. But I’m reminded how very hands on we were in just about everything. And that’s relevant given the buzz today about how kids might not be getting enough practical science and engineering experience in schools (I’m thinking of comments most recently made by Martin Rees in the Reith Lectures).

No one is arguing kids need a nuts and bolts knowledge of all modern gadgetry, but I do think off-syllabus projects like the Stantec Zebra (but perhaps less dangerous) are a good thing in schools. They show how diverse academic subjects come together in an application, making the theory real. This is pretty much my mantra in this earlier post about the Young Scientists of the Year competition. I would have thought such projects give a school a sense of identity and foster a bit of team spirit?

But it’s really an area I’m out of touch with. Does this type of stuff happen in lunchtime science clubs? Is there time in the curriculum? Do teachers have the time and/or skills? Or has our health & safety culture, however worthy, killed off anything interesting?

Also of interest

Kids Today Need a License to Tinker (Guardian 28/8/2011)